The first trial under Hong Kong’s new national security law begins Wednesday without a jury, a landmark moment for the financial hub’s fast-changing legal traditions.

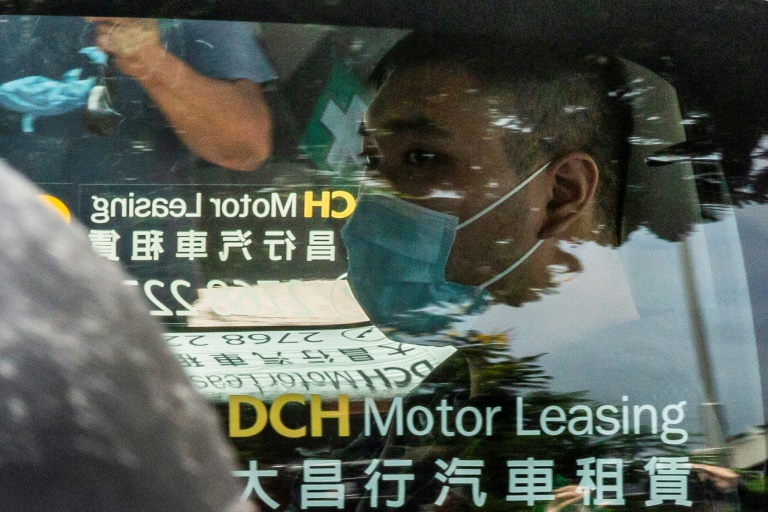

Tong Ying-kit, 24, was arrested under the new law the day after it came into effect when he allegedly drove his motorbike into a group of police officers during protests on July 1 last year.

Footage showed his motorbike was flying a flag that read “Liberate Hong Kong, revolution of our times”, a popular protest slogan now deemed illegal under the security law.

Tong faces charges of inciting secession and terrorism, as well as an alternative charge of dangerous driving.

Two courts rejected Tong’s plea to have his case heard by a jury, which his legal team had argued was a constitutional right given that he faces a life sentence if convicted.

Trial by jury has been a cornerstone of Hong Kong’s 176-year-old common law system and is described by the city’s judiciary on its website as one of the legal system’s “most important features”.

But the national security law, which was penned in Beijing and imposed on Hong Kong last year after huge and often violent democracy protests, allows for cases to be tried by three specially selected judges.

The city’s justice secretary invoked the no jury clause for Tong’s trial arguing that juror safety could be compromised in Hong Kong’s febrile political landscape, a decision first revealed by AFP.

Tong’s legal team has yet to decide whether to bring their case to Hong Kong’s Court of Final Appeal.

However, the wording of Beijing’s security law makes clear that it trumps any local regulations in the event of a dispute, something successive court rulings have already upheld.

Tong’s case is unusual because he is the only Hong Konger so far charged under the security law with an explicitly violent act.

More than 60 people have now been charged under the provision, including some of the city’s best-known democracy activists, but their offences are related to political views or speech that authorities have declared illegal.

Hong Kong and Chinese authorities have hailed the security law as successfully restoring stability after the demonstrations that convulsed the finance hub in 2019.

But it has also transformed the city’s political and legal landscape — which was historically firewalled from the authoritarian mainland.

The law also grants China jurisdiction over some cases and empowers mainland security agents to operate openly in the semi-autonomous city for the first time.

Critics, including many western nations, say China has broken its “One country, two systems” promise that Hong Kong could maintain key freedoms after its handover from Britain.