(Bloomberg) — Beijing’s clampdown on the booming private education industry has shocked even some of the most seasoned China watchers, prompting a rethink of how far Xi Jinping’s Communist Party is willing to go as it tightens its grip on the world’s second-largest economy.

The crash in tutoring stocks that began on Friday spread this week across the tech sector and beyond, after authorities confirmed reports they would ban a swathe of the education industry from making profits. It’s the government’s most extreme step yet to rein in private businesses that regulators blame for exacerbating inequality, increasing financial risk and — in the case of some tech titans –- challenging Beijing’s authority.

With losses in Chinese tech and education stocks now exceeding $1 trillion since February, the questions reverberating across trading desks from Shanghai to New York are where regulators might strike next and whether markets are properly discounting regulatory risk. Property-management and food-delivery companies were among the biggest losers on Monday after Beijing signaled tighter rules for both sectors.

While some investors say the selloff has created buying opportunities, ongoing clampdowns on everything from internet platform operators to commodities producers and China’s gargantuan real estate industry suggest plenty of room for more surprises — especially for international investors as Xi’s government shows less concern than its predecessors did about spooking foreign capital.

Goldman Sachs Group Inc.’s sales desk summed it up this way in a note to clients: “Even when you think China risk is priced…it can get worse.”

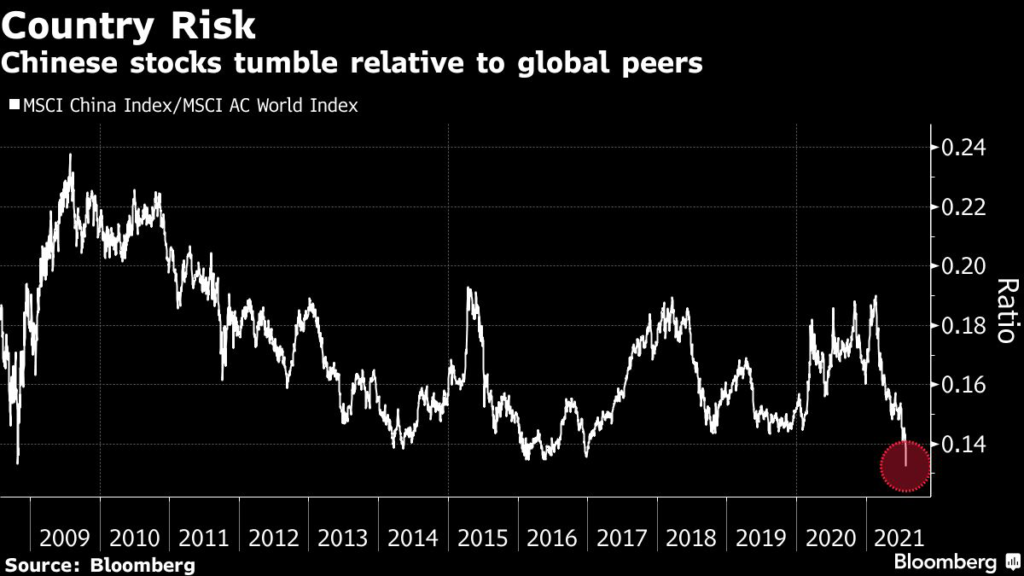

Monday’s rout underscored just how widespread that concern has become. All 10 industry groups in the MSCI China Index posted declines as the gauge sank 5.6%, the most since March 2020. The selloff was all the more striking given MSCI’s All-Country World Index jumped on Friday to within a hair’s breadth of its all-time high. The China gauge dropped another 1.5% at 10:37 a.m. on Tuesday, extending its slide from this year’s peak to 28%. It’s now trading at about 1.3 times book value, the biggest valuation discount on record relative to global peers.

In the U.S., the Nasdaq Golden Dragon China Index plunged 7% Monday to close at its lowest level in 13 months. The gauge — which tracks 98 of China’s biggest firms listed in the U.S. — posted its two-day drop since 2008 and has lost $769 billion in value since reaching a record high in February.

“Everybody’s in the cross-hairs,” said Fraser Howie, an independent analyst and co-author of books on Chinese finance who has been following the country’s corporate sector for decades. “This is a very difficult environment to navigate, when over the weekend your business can basically be written down to zero by state edict, how on Earth are you to plan for that?”

Regulatory risk is nothing new in China, but rarely have global investors had to cope with such an onslaught of rules that threaten to curb growth and in some cases decimate entire business models. Beijing’s surprise scuttling of Jack Ma’s initial public offering of fintech giant Ant Group Co. in November looks increasingly like the high-water mark for an era of relatively loose regulation for the country’s private sector.

Among the investment firms selling on Monday was BNP Paribas Asset Management, which oversees about $559 billion worldwide and was already underweight China heading into the rout. “Investors are looking to figure out if there are more sectors that can face this,” said Zhikai Chen, the firm’s head of Asian Equities. “We are reducing some exposure.”

Chen said it’s too early to judge whether the Chinese government’s attitude toward the private sector has permanently shifted, noting that authorities have in some ways made it easier for companies and investors to access capital markets in recent years.

But that was also true for the education industry –- a darling of Wall Street — until regulators began signaling a potential clampdown earlier this year. The rules were ultimately stricter than even some of the most bearish predictions, banning companies that teach school curriculums from making profits, raising capital or going public. They have effectively obliterated the model underpinning a $100 billion industry.

“What has happened in the education/tech sector could happen in other sensitive and strategic sectors, such as media, healthcare or whatever,” said Claude Tiramani, a Paris-based fund manager at LA Banque Postale Asset Management SA, who oversees about 600 million euros ($708 million) in investments. “Because of these uncertainties, I think the Chinese market could get de-rated.”

Tiramani, who holds companies including New Oriental Education & Technology Group and Tencent Holdings Ltd., said he raised the cash position to the maximum allowed in his portfolio in the last three months, and took advantage of any bounce-back to “substantially” reduce exposure to technology companies.

The clampdown in some ways mirrors Beijing’s broader campaign against the growing power of Chinese internet companies, including Didi Global Inc. to Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. But it also stems from a deeper backlash against an industry that has been criticized for putting too much pressure on children, burdening parents with expensive fees, and exacerbating inequality. China’s government has been prioritizing efforts to boost the country’s birthrate as it tries to prevent an aging population from further weighing on economic growth.

“I don’t think this is so much about foreign investors, I think it is more about trying to restore equality for K-12 education,” said Joshua Crabb, a senior portfolio manager at Robeco in Hong Kong.

Still, it’s a reminder for global investors of the importance of tracking the Chinese government’s shifting priorities.

The temptation is to view the market in a similar way to major peers like the U.S., but Beijing often moves more quickly and decisively because it lacks checks and balances, said an executive at one of the world’s biggest private equity firms who has backed at least one U.S.-listed Chinese education company. He asked not to be identified given the sensitivity of the subject. Another private equity investor who focuses on Asia called the crackdown a wake-up call for investors who have overlooked Chinese regulatory risks in recent years.

New Oriental Education & Technology Group’s Hong Kong shares still had 13 analyst buy ratings and just one “underweight” as of Monday, according to data compiled by Bloomberg, after plunging more than 40% for a second straight session. It fell another 4% on Tuesday.

Food-delivery giant Meituan, with 56 buys and no sells, has tumbled 20% this week after the government posted notices that online food platforms must respect the rights of delivery staff and ensure workers earn at least the local minimum income. The stock has lost half its value since mid-February.

Meanwhile, Evergrande Property Services Group Ltd. has slumped 16% this week after major Chinese policy-making bodies collectively issued a three-year timeline for bringing “order” to the property sector, long under scrutiny due to an excessive buildup of leverage among home-buyers and developers. The announcement detailed punishments for a range of transgressions by businesses in real estate development, home sales, housing rentals and property management services.

Read more on Evergrande’s challenges here.

Some investors have been seeking shelter in strategic sectors viewed as beneficiaries of Xi’s policies. These include electric vehicle makers and companies involved in transporting and storing cleaner energy that may help China’s plans to become carbon neutral by 2060. Local analysts have also advocated buying shares of semiconductor makers as the nation seeks technological self-sufficiency.

For Jian Shi Cortesi, a portfolio manager at GAM Investment Management in Zurich, the key is to avoid companies that the government might determine are benefiting a “small group at the expense of broader prosperity.” Those businesses are likely to face tighter regulation, Cortesi said, pointing to live streaming as one area that may be vulnerable. At the same time, she’s looking for chances to buy shares that have been unduly punished in the selloff.

“Many high-growth Chinese companies have already dropped by half in the past few months and many investors have started to panic — all these tell us it is the time to look for good opportunities to enter,” Cortesi said. “Of course, it’s important to be selective.”

(Updates with Tuesday trading in Hong Kong.)

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.