A Hong Kong court will lay down a marker on the city’s future legal landscape Tuesday when it delivers its verdict in the first trial using a national security law imposed by China to stamp out dissent.

One of the key elements in the verdict will determine whether flying a popular protest flag can be deemed an act of secession, one of the new national security crimes that carry up to life in prison.

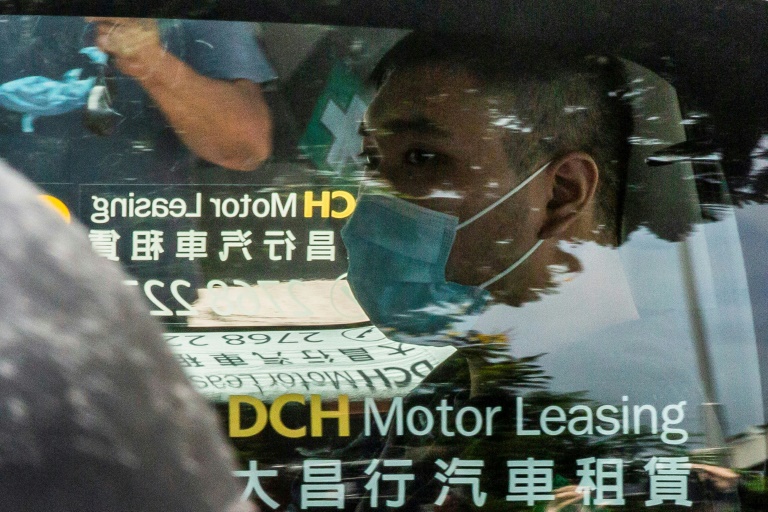

Tong Ying-kit, 24, is charged with inciting secession and terrorism after he drove a motorbike into police while flying a protest flag during a rally on July 1 last year, the day after the national security law was enacted.

The flag read “Liberate Hong Kong, revolution of our times”, a ubiquitous slogan during the huge and often violent pro-democracy protests that convulsed the city two years ago.

The 15-day trial was heard without a jury in a significant departure from the financial hub’s common law tradition, and will be decided by three judges handpicked by the city’s leader to try national security crimes.

The verdict will give clues as to how Hong Kong’s judiciary will interpret Beijing’s broadly worded security law and whether the semi-autonomous city’s courts will become more like those in authoritarian mainland China.

More than 60 people have been charged under the law, including some of the city’s best-known democracy activists such as Jimmy Lai, owner of the now-shuttered Apple Daily newspaper.

Most of those charged are now in jail awaiting trials.

The prosecution argued that Tong, a former waiter, was pursuing a “political agenda” that caused “great harm to society” and therefore met the bar for terrorism.

Prosecutors said the flag he flew promoted Hong Kong’s independence and was therefore secessionist.

He also faces a charge of dangerous driving.

– Slogan now illegal?

–

Days of testimony were spent on the flag, with university professors called by both sides to explain the slogan’s meaning.

Defence experts argued the slogan meant many things to different people in what was a leaderless protest movement that included a broad spectrum of political views, from people advocating genuine independence from China to those wanting greater democracy and police accountability.

“It is actually quite difficult, quite traumatic or even misleading to think that one idea only means one thing in my mind in all circumstances,” said Francis Lee, Chinese University of Hong Kong’s journalism school head, who was called as a defence witness.

The vast majority of those charged under the security law were arrested for expressing political views that authorities say are now illegal.

A ruling in the prosecution’s favour would illustrate how far political free speech has been curtailed in Hong Kong and give legal backing to the criminalisation of dissent.

In mainland China, opaque courts answer to the Communist Party and conviction is all but guaranteed, especially in political or national security cases.

Hong Kong maintains an internationally respected common law system that is the bedrock of its business hub status.

But the security law has radically transformed the political and legal landscape of the city, which China promised could keep key liberties and autonomy after its 1997 return.

China has jurisdiction over some cases and has allowed its security agents to operate openly in Hong Kong for the first time.

It also allows for cases to be tried by judges instead of juries and bail is largely denied for those arrested.

The city’s justice secretary invoked the no-jury clause for Tong’s trial, arguing that juror safety could be compromised in Hong Kong’s febrile political landscape.

Tong pleaded not guilty to all charges and did not take the stand during the trial.