From agriculture to housing to transportation, economic growth has historically depended on burning through finite natural resources and rearranging natural landscapes.

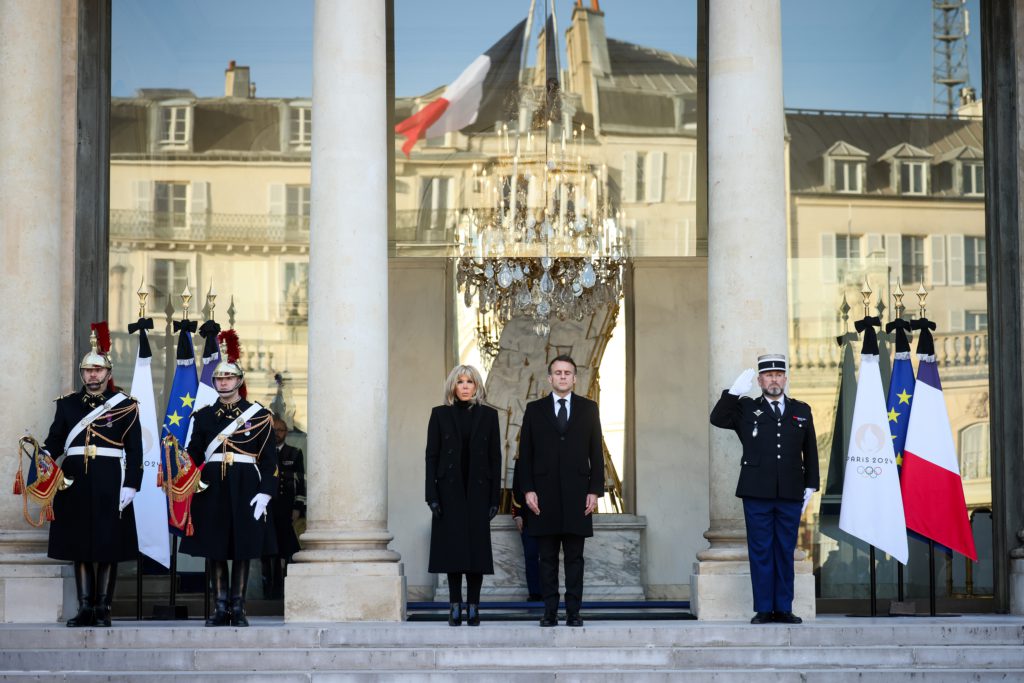

As the IUCN World Conservation Congress kicks off in France on Friday, an urgent question will be how to reduce the devastation wrought by humanity on the environment.

One idea gaining currency is to assign nature an economic value.

“It’s the only way to speak the same language as political decision-makers,” Nathalie Girouard, an expert on environmental policy at intergovernmental think tank OECD, told AFP.

“We have increased economic growth at the expense of nature.”

Chemical-intensive agriculture, over-fishing, pollution and climate change are all pushing ecosystems to the brink of collapse.

For business, putting a monetary value on nature means that damaging resources such as breathable air and drinkable water becomes not just a survival risk, but a financial one.

But experts are divided on how to measure “natural capital”, and some argue that it should not be done at all.

– Natural capital –

During most of industrialisation, the intrinsic value of nature’s bounty — air, fresh water and oceans, for example — was not recognised because it cost nothing to consume or pollute.

The concept of natural capital, some conservationists and economists argue, makes it possible to evaluate ecosystems in terms of the “services” they provide — and the cost of repairing them when damaged.

Mary Ruckelshaus, head of the Natural Capital Project at Stanford University, acknowledges that it is a complex task.

She gives the example of their work in Belize where indigenous populations, fishermen and real estate developers all value mangrove forests, but have very different ideas of what to do with them.

Some will value their capacity to dampen storm surges, while others would prefer to see aquaculture or sandy beaches in their place.

“They help protect coastlines, communities from sea-level rise and hurricanes,” she says, adding that such a “service” is worth millions, in some cases billions, of dollars.

“You can monetise that.”

But she says such numbers cannot always cover the true cost of harming a resource.

“What’s the cultural value of the mangrove forest to an indigenous community who lives in Belize? Priceless,” she continues.

Ruckelshaus says the best way to assign value to ecosystems is to get all the interested parties around a table.

“If you articulate and quantify where the most value is for each stakeholder, often you don’t have as many trade-offs as you think,” she says.

– Regulation still key –

When you scale things up, the numbers are eye-popping.

Some $44 trillion (37 trillion euros) of annual economic value generation — half of the world’s gross domestic product — is moderately or highly dependent on nature, according to the World Economic Forum.

Using the natural capital as the guiding principle, proponents favour integrating natural resources into the calculation of a country’s wealth.

“This is the first step to integrating biodiversity in national strategies and plans and to bring about real change, thanks to clear targets and indicators,” said Girouard.

But the concept remains controversial for some.

In 2018 British writer and environmentalist George Monbiot argued against the idea, which he said “reinforces the notion that nature has no value unless you can extract cash from it”.

French author, environmentalist and member of the European Parliament Aurore Lalucq agrees.

“We don’t need to give a price to bees — we need to outlaw the pesticides that kill them,” she told AFP.

She believes that legislation, not financial incentive, will work best to protect remaining ecosystems.

“We need to regulate, make practices illegal and invest in green infrastructure and biodiversity,” she said.

Ruckelshaus acknowledges that the monetary value system has its limitations and that government regulation remains crucial.

“Valuing nature… gives everybody the same information but it doesn’t guarantee that everyone will make the decision to protect nature,” she said.