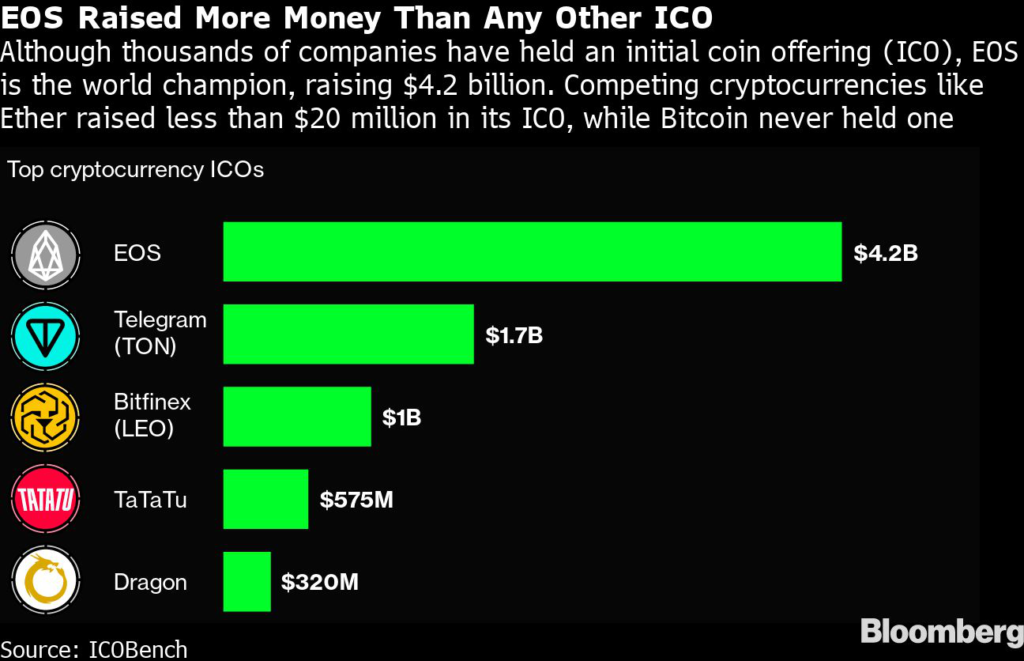

(Bloomberg) — It would become the biggest digital token sale on record. Over 11 months in 2017 and 2018, a little known software maker named Block.one held an initial coin offering for a new cryptocurrency, raising more than $4 billion.

Backed by billionaire heavyweights including PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel, hedge fund magnates Alan Howard and Louis Bacon, and German entrepreneur Christian Angermayer, Block.one said it would use the money to build tools that would speed adoption of blockchain technology.The newly minted currency, EOS, soon became mired in controversy.

The U.S.

Securities and Exchange Commission fined Block.one $24 million in 2019 for failing to register the ICO, and token holders sued Block.one last year, calling the sale a “fraudulent scheme” and alleging that the company violated securities laws by making “false and misleading statements about EOS, which artificially inflated the prices for the EOS securities and damaged unsuspecting investors.” And some programmers and digital asset managers have said that the company for years showed scant progress toward its mission.Newly published research by forensic financial analysis firm Integra FEC, led by University of Texas at Austin McCombs School of Business finance professor John Griffin, raises fresh concerns about the EOS initial coin sale.

Griffin, in interviews and a 14-page paper posted to the Integra website Tuesday, highlights a pattern of what he says are suspicious trades during the ICO. The transactions, between potentially connected associates, “pumped up” the price of EOS and induced unwitting investors to buy the currency, he alleges in the paper.

“The seemingly artificial demand from the suspicious accounts had two effects,” Griffin wrote.

“It directly manipulated EOS’s offering price upward through the extra buying and inflated the market value of the token. Second, it created the false impression of value of the token, which enticed others to want to purchase the ICO token.”

Griffin identified 21 accounts that over the course of the ICO engaged in regular, unusually large purchases of EOS, followed by sales of the currency to an exchange less than an hour later, a process he refers to as recycling.

In all, the recycled funds amounted to 1.206 million Ether, the cryptocurrency used to trade EOS, or $814.6 million, Griffin estimates, saying the actual amount could be substantially higher and “could have also consisted of other means to manipulate the EOS price upward.”

The paper doesn’t identify the owners of the accounts, and Griffin doesn’t allege wrongdoing by any specific individual or Block.one itself.

While crypto transactions are traceable through publicly available information, the entities behind them are harder to pinpoint. Griffin said neither he nor his firm received compensation for the paper.In a statement in response to the paper, Block.one pointed to a report issued in July by the law firm Clifford Chance LLP that said it “found no evidence of any arrangements between Block.one and third parties by which third parties bought tokens on Block.one’s behalf.” Clifford Chance, which completed the analysis with help from PwC and DMG Blockchain Solutions Inc., also said it found “no evidence that Block.one purchased tokens on the primary market.” (Block.one had commissioned the study in 2019 amid allegations that surfaced as early as 2017 over whether Block.one purchased its own tokens during the sale.)

Griffin’s paper “fails to acknowledge this and makes many errors in fact and logic in pursuit of a false thesis that can be easily disproven with publicly available information,” Block.one said in the statement. Block.one’s statement didn’t elaborate on what it believes those errors are.

Block.one investors Thiel and Angermayer didn’t respond to requests for comment, while Bacon and Howard declined to comment.Questions over the ICO take on added significance now that Block.one has shed more light on how it plans to use the money the company earned as revenue from it.

Block.one said in May it will use proceeds from the sale and other sources of funding to launch a subsidiary called Bullish, a cryptocurrency exchange valued at about $9 billion. The exchange, set to go public this year through a merger with a special purpose acquisition company, boasts several of the same investors who backed Block.one, including Thiel, Howard, Bacon and Angermayer.

Other Bullish investors include Hong Kong scion Richard Li and a unit of Japanese investing giant SoftBank Group Corp. Its three-person board is comprised entirely of Block.one executives.Bullish is preparing its public debut just as concerns around cryptocurrencies crescendo.

SEC Chairman Gary Gensler is contemplating tighter oversight of digital money, and regulators around the world are grappling with how to rein in the excesses of a $2 trillion craze that involves wild price swings and a dearth of disclosure around the businesses that underlie publicly traded coins.

“We just don’t have enough investor protection in crypto,” Gensler said in a recent speech, comparing it to the Wild West. “This asset class is rife with fraud, scams and abuse in certain applications.

. . . In many cases, investors aren’t able to get rigorous, balanced and complete information.”

How It WorkedHere’s how the trading volley played out, according to Griffin. First, parties transferred large amounts of Ether, another cryptocurrency, to specially created accounts on an exchange.

Account holders then used Ether to purchase newly minted EOS coins at Block.one’s crowdsale — essentially an auction. But rather than hold onto EOS, as the other EOS buyers did, the parties “quickly and repeatedly” sold the EOS to the same exchanges for Ether — typically within 40 minutes of purchasing it.

Those funds were then used to buy more EOS.This behavior was unusual for several reasons, according to Griffin:

-

Account holders typically sold EOS at a loss, instead of earning a profit by holding EOS throughout the ICO.

-

The accounts bought and sold a similar amount of Ether on a daily or weekly basis and, unlike other accounts that participated in the sale, “appear almost solely created for this purpose.”

-

Griffin flagged accounts as suspicious if they invested $15 million or more, compared with less than $10,000 for a typical account.

-

The Ether sent back from EOS’s crowdsale wallet to the Bitfinex exchange was delivered in an unusually complicated manner consistent with trying to obfuscate the identity and tracking of the funds, he said.

“The suspicious accounts created legitimacy and the perception of wide-scale interest in EOS, and thus were able to make EOS move from an obscure ICO to become a token of widely perceived value,” Griffin said.

EOS peaked at $21.54 in April 2018 before falling below $2 that December.

Interest in the token revived in May when Block.one announced plans for Bullish, and it was recently trading at about $4.97.

“The possible motive of arbitrage is an alternative hypothesis examined in the report, but — contrary to profitable arbitrage trading — the repeated trading pattern appears generally unprofitable,” Griffin said. “Sophisticated traders typically don’t repeatedly lose money on a trade unless they have an offsetting profit source or motive.”

A person close to Block.one disputes these findings, saying that the transactions reflect systematic traders taking advantage of price arbitrage. This person also said that selling the tokens would have had the effect of depressing the price of EOS, just as purchasing it buoyed the currency’s price. No one would have the incentive to do that, said the person, who added that he didn’t know who the counterparties were. Other factors could explain the rapid successions of buying and selling EOS around the time of its initial offering.

A May 2018 posting on the software collaboration site GitHub describes an arbitrage opportunity generated by price discrepancies in the crowdsale and on crypto exchanges like Binance. According to the writer, EOS coins distributed in the crowdsale chronically sold for less than coins trading simultaneously on the secondary market, and nimble traders who could buy and sell fast enough could sometimes lock in fast profits.Griffin defended his work. Supply was fixed each day, so purchasing the tokens in the sale would buoy the price, he said in an interview. It was unprofitable to buy at the crowdsale and sell at the exchange almost twice as often as that same trade was profitable, he explained.

“Selling through the exchange could have minimal impact on the price, especially since it can be sold slowly and in a liquid market,” he said.

He also disputed the idea that these trades were carried out simply to take advantage of price differences. “Market makers make a spread and make money on the spread,” he said. “These traders consistently lost money on their trades.

Why would one engage in a losing strategy unless making money somewhere else?”At Bloomberg’s request, Cornell Law School Professor Robert Hockett reviewed Griffin’s research and called the analysis “impeccable.”

“There’s enough smoke here to suggest there’s a fire,” said Hockett, who specializes in corporate law and financial regulation.

Hockett said the actions described in Griffin’s report, if true, could violate the Securities Act of 1933 and the Exchange Act of 1934, which prohibit fraud and manipulative activities. “This is what the SEC would call classic fraud and pump and dump.

This is taking advantage of retail investors who don’t know what’s going on underneath and could be easily fooled.” The SEC and Department of Justice “should definitely be investigating,” he said.Bloomberg Intelligence analyst James Seyffart also examined Griffin’s research using Etherscan, a tool for searching the Ethereum blockchain, a digital ledger of cryptocurrency transactions, and reached similar conclusions.

“The only reason they would be doing this is because they’re pumping or have failed miserably at attempting an arbitrage trade,” Seyffart said.

“This definitely deserves a closer look.”The SEC and Justice Department declined to comment.

While the Clifford Chance report was extensive, it also admits to limitations. In a section entitled “assumptions and limitations,” the report said “Block.one shareholders, employees, equity holders, directors, officers, suppliers and consultants (past, present or future) were permitted to participate in the token sale on the same terms as all other purchasers,” using their own funds — meaning that any such activity was outside the scope of the review of accounts, or wallets.

Also, the report only examined cryptocurrency wallets owned by Block.one with addresses provided by Block.one.“Given the caveat that their analysis only applies to blockchain addresses that were provided by Block.one, the report seems to be unrelated to what we investigated,” Griffin said in an interview. “Due to the anonymous nature of the blockchain, it is very difficult to confirm whether the list of Block.one addresses analyzed by Clifford Chance and PwC is comprehensive.”

Clifford Chance explained its methodology in a statement, saying that while the review was limited to Block.one wallets, “our review of Block.one’s documents and information went much further.”Wallet WithdrawalsRegistered in the Cayman Islands, with offices in Hong Kong and the Washington, D.C., area, Block.one was established in 2016 by Dan Larimer, a Virginia Tech-trained software engineer and entrepreneur, and Brendan Blumer, an entrepreneur whose previous ventures include selling in-game items and creating software for realtors in India.

Brock Pierce, the former child actor who co-founded a coin that became Tether, was an early adviser. Block.one’s early investors included Bitmain Technologies, the Bitcoin mining giant co-founded by Chinese billionaire Jihan Wu, and billionaire Mike Novogratz’s Galaxy Digital, a cryptocurrency-focused financial services provider that plans to go public on a U.S.

exchange later this year.Block.one was birthed in the ICO heyday — when one obscure company after another unveiled plans to raise funds by issuing new virtual tokens, typically accompanied by a white paper outlining business plans.

Few had any actual products, and many discussed plans in the vaguest terms. In its white paper, Block.one said it would treat the ICO proceeds as revenue and use it for a “consulting business focusing on helping businesses reimagine or build their businesses on the blockchain,” according to the SEC, citing a website touting the coin.One of Griffin’s findings dovetails with an allegation outlined in the 2020 token holder lawsuit.

This concerns multiple withdrawals from what’s known as a crowdsale wallet, where coin investors deposit their payments to Block.one. Typically, these funds would remain in the wallet until completion of the ICO.

But in the EOS sale, 2.895 million Ether ($1.72 billion) were withdrawn during the sale and sent to one exchange in particular, Bitfinex, Griffin found.

That accounted for 39% of all Ether raised and made Bitfinex the biggest destination of funds, he said.

Griffin also raised flags over how the funds made their way to Bitfinex, saying they were done in a way that made them hard to track.

“These transactions took place over a series of four hops to overlapping Bitfinex deposit addresses, the design of which is consistent with obfuscating deposits to common accounts at Bitfinex,” he wrote.

The token holder lawsuit explored other ways these withdrawals might be problematic.

Block.one executives “permitted the funds to be withdrawn nearly a hundred times, accounting for close to 90% of the total funds raised throughout the ICO period and averaging one withdrawal every three to four days,” the lawsuit alleged.

“While withdrawal of funds during an ICO is not expressly prohibited, there are significant concerns about how the withdrawn funds might be used, e.g., to buy tokens on cryptocurrency exchanges, resulting in artificially inflated demand for EOS, increasing market price, and fueling speculation and interest in the sale,” the lawsuit said. Block.one disclosed in June that it paid $27.5 million to settle the lawsuit, saying that it was “without merit and filled with numerous inaccuracies.” The company didn’t specify what it believes those inaccuracies were.Clifford Chance’s report addressed withdrawals, saying that Block.one withdrew funds, in the form of Ether, from wallets related to the coin sale, including the funding wallet.

Block.one said it made the withdrawals to prevent theft and to hedge against fluctuations in the value of Ether, according to Clifford Chance. Another reason was to avoid selling a large Ether holding in one fell swoop, the report said.

If that had happened, it “would have been far more likely to negatively impact Ether prices than sales in smaller tranches over a long period of time,” Clifford Chance wrote.Griffin has unearthed irregularities in cryptocurrency trading before.

He alleged that Bitcoin’s surge in 2017 was triggered by manipulation and that a single participant, or whale, was likely behind the misconduct. He contended that a single entity on Bitfinex, using Tether, was seemingly capable of supporting the price of Bitcoin when it fell below a certain threshold.

A lawyer representing Tether disputed Griffin’s research at the time, saying it was based on an insufficient data set. The findings nevertheless roiled digital asset markets and contributed to investor skepticism.Block.one said in May it would bankroll Bullish with $10 billion, funding that includes 20 million EOS coins and 164,000 Bitcoin.

Investors, including Thiel’s Founders Fund, Thiel Capital, Howard, Bacon, Angermayer, Li, investment bank Nomura and Galaxy Digital, put in an additional $300 million in Bullish. Thiel, Howard, Li and Angermayer will also serve as board advisers.

The exchange’s directors are Blumer as well as Kokuei Yuan and Andrew Bliss, all of them Block.one executives.

Li and Nomura didn’t respond to requests for comment. Galaxy declined to comment.Block.one has faced concerns over the effectiveness of the technology it helped create and the vitality of its related developer network.

Many software developers have abandoned the EOS effort. Electric Capital, which analyzes the crypto developer community, found that the number of monthly active EOS developers fell to about 70 in July from 130 at the beginning of 2020.

“I think its technology is now outmoded,” said Aaron Brown, a crypto investor who writes for Bloomberg Opinion.

“It’s not surprising to find it revitalizing when crypto came back, and also taking advantage of the boom in SPACs. But it has yet to demonstrate any technical successes.”To be sure, Block.one’s technology has gained some traction. Accounting firm Grant Thornton said last year it would let clients handle intercompany transactions using what it later confirmed was blockchain technology based on EOS. Grant Thornton declined to comment on the progress of the initiative.While it prepares for the Bullish market debut, Block.one may have trouble luring crypto investors who believe they got burned in the ICO, said Katie Talati of Arca, a digital-asset manager.

In a March 19, 2019, email to shareholders, Block.one said its assets, including cash and investments, totaled $3 billion at the end of the preceding February. About $2.2 billion of those holdings were in liquid fiat assets, such as U.S.

government bonds.

“They are going to have bad PR associated with the project that’s going to follow them,” she added. “Crypto is very community driven — if you are going to burn your community, it’s hard to rebuild that.”

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.