(Bloomberg) — Days before Christmas in 2015, Juniper Networks Inc. alerted users that it had been breached. In a brief statement, the company said it had discovered “unauthorized code” in one of its network security products, allowing hackers to decipher encrypted communications and gain high-level access to customers’ computer systems.

Further details were scant, but Juniper made clear the implications were serious: It urged users to download a software update “with the highest priority.”

More than five years later, the breach of Juniper’s network remains an enduring mystery in computer security, an attack on America’s software supply chain that potentially exposed highly sensitive customers including telecommunications companies and U.S. military agencies to years of spying before the company issued a patch.

Those intruders haven’t yet been publicly identified, and if there were any victims other than Juniper, they haven’t surfaced to date. But one crucial detail about the incident has long been known — uncovered by independent researchers days after Juniper’s alert in 2015 — and continues to raise questions about the methods U.S. intelligence agencies use to monitor foreign adversaries.

The Juniper product that was targeted, a popular firewall device called NetScreen, included an algorithm written by the National Security Agency. Security researchers have suggested that the algorithm contained an intentional flaw — otherwise known as a backdoor — that American spies could have used to eavesdrop on the communications of Juniper’s overseas customers. NSA declined to address allegations about the algorithm.

Juniper’s breach remains important — and the subject of continued questions from Congress — because it highlights the perils of governments inserting backdoors in technology products.

“As government agencies and misguided politicians continue to push for backdoors into our personal devices, policymakers and the American people need a full understanding of how backdoors will be exploited by our adversaries,” Senator Ron Wyden, a Democrat from Oregon, said in a statement to Bloomberg. He demanded answers in the last year from Juniper and from the NSA about the incident, in letters signed by 10 or more members of Congress.

Against that backdrop, a Bloomberg News investigation has filled in significant new details, including why Sunnyvale, California-based Juniper, a top maker of computer networking equipment, used the NSA algorithm in the first place, and who was behind the attack.

►Juniper installed the NSA code — an algorithm with the unwieldy name Dual Elliptic Curve Deterministic Random Bit Generator — in NetScreen devices beginning in 2008 even though the company’s engineers knew there was a vulnerability that some experts considered a backdoor, according to a former senior U.S. intelligence official and three Juniper employees who were involved with or briefed about the decision.

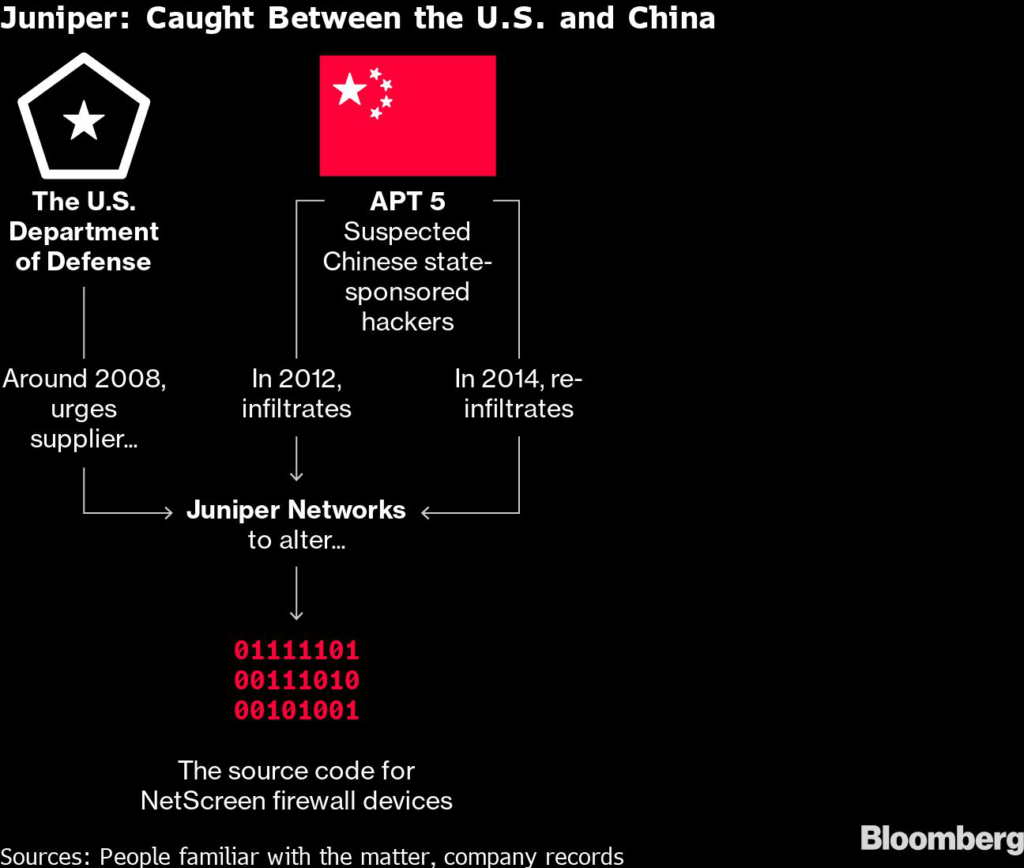

The reason was that the Department of Defense, a major customer and NSA’s parent agency, insisted on its inclusion despite the availability of other, more trusted alternatives, according to the official and the three employees. The algorithm had just become a federal standard at NSA’s behest, alongside three similar ones that weren’t mired in controversy, and the Pentagon tied some future contracts for Juniper specifically to the use of Dual Elliptic Curve, the employees said. The request prompted concern among some Juniper engineers, but ultimately the code was added to appease a large customer, the employees said. The Department of Defense declined to discuss its relationship with Juniper.

►Members of a hacking group linked to the Chinese government called APT 5 hijacked the NSA algorithm in 2012, according to two people involved with Juniper’s investigation and an internal document detailing its findings that Bloomberg reviewed. The hackers altered the algorithm so they could decipher encrypted data flowing through the virtual private network connections created by NetScreen devices. They returned in 2014 and added a separate backdoor that allowed them to directly access NetScreen products, according to the people and the document.

While previous reports have attributed the attacks to the Chinese government, Bloomberg for the first time has identified the hacking group and its tactics. In the past year, APT 5 is suspected of engineering intrusions into dozens of companies and government agencies, according to cybersecurity firm FireEye Inc., which added that the hackers have long sought to identify — or introduce — vulnerabilities into encryption products to enable breaches of their ultimate targets: defense and technology companies in the U.S., Europe and Asia.

►After detecting the 2012 and 2014 breaches of its network, Juniper failed to understand their significance or recognize that they were related, according to the two people involved with Juniper’s investigation and the internal document. At the time, the company found that hackers had accessed its e-mail system and stolen data from infected computers, but investigators mistakenly believed the intrusions were separate and limited to theft of corporate intellectual property, according to the people and the document.

Juniper declined to answer specific questions from Bloomberg. The company provided a statement that reiterated its comments from 2015 about the operating system for its Netscreen products, which is called ScreenOS.

“Several years ago, during an internal code review, Juniper Networks discovered unauthorized code in ScreenOS that could allow a knowledgeable attacker to gain administrative access to NetScreen devices and to decrypt VPN connections,” the company said. “Once we identified these vulnerabilities, we launched an internal and coordinated external investigation and worked to develop and issue patched releases for the impacted devices. We also immediately and successfully reached out to affected customers, strongly recommending that they update their systems and apply the patched releases with the highest priority.”

In a July 2020 response to Wyden and other members of Congress, Juniper provided few new details of the case but blamed the intrusions on a “sophisticated nation-state hacking unit.” NSA told Wyden’s staff in 2018 that there was a “lessons learned” report, but the agency “now asserts that it cannot locate this document,” according to a Wyden aide. Reuters previously reported NSA’s claim that the document had been lost.

“I am extremely disappointed that the NSA refused to answer my questions about their reported role in the Juniper affair,” Wyden said in his statement.

The NSA declined to comment to Bloomberg. China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs said in a statement, “China firmly opposes and combats all forms of cyberattacks and opposes arbitrary labeling and malicious attacks on China in the absence of conclusive evidence.”

“The U.S. government and related agencies have carried out large-scale, organized and indiscriminate cyber theft, surveillance and attacks on foreign governments, companies and individuals,” according to the ministry. “The U.S. should stop being the thief who calls out to catch the thief.”

Bloomberg’s findings add new details to a long-running and contentious debate over the use of backdoors — secret digital pathways that bypass security measures and allow high-level access to computer networks.

Some of the government’s prior efforts to install backdoors in U.S. products are well known, including an ill-fated effort to equip American-designed telecommunications equipment with NSA’s Clipper chip in the early 1990s. Two decades later, leaked documents from former NSA contractor Edward Snowden revealed some of the agency’s secret techniques for penetrating encryption, lending credence to allegations that NSA installed a backdoor in the Dual Elliptic Curve algorithm, according to multiple news articles based on the files.

More recently, in October, the Department of Justice under then-President Trump published a joint statement with counterparts in the U.K. and Australia saying modern encryption poses “significant challenges to public safety” and urging technology companies to implement “reasonable, technically feasible solutions” to allow authorities backdoor access when required.

The government’s classified policies around the practice are shrouded in such secrecy that critics worry about potential abuses.

Juniper’s case is “a perfect example of the danger of government backdoors,” said Jennifer Stisa Granick, surveillance and cybersecurity counsel for the American Civil Liberties Union. “There is no such thing as a backdoor that only the U.S. government can exploit.”

NetScreen was an innovative company that Juniper acquired for $4 billion in 2004. Its products combined a firewall, which controls who can access computers on a network, and VPNs, which encrypt users’ data as it travels over the internet.

Customers included major banks and nine of the 10 top global telecommunications companies, according to a Juniper investor presentation. The Defense Department was a major customer, too, and enjoyed direct access to high-ranking Juniper employees.

At least once a year, Pentagon officials traveled to Juniper’s headquarters to meet with a small group of NetScreen’s senior engineering managers to review planned product upgrades and ensure they would meet federal security standards, according to the former senior U.S. intelligence official and the three Juniper employees who either attended or were briefed about the meetings.

By 2008, the Department of Defense had presented Juniper with a tricky proposition: If the company wanted NetScreen to qualify for certain future contracts with the military and intelligence agencies, it would need to add the Dual Elliptic Curve algorithm to NetScreen’s ScreenOS software, the four people said.

The NSA algorithm, which was purported to improve security for encrypted communications, had been approved as a standard for government systems despite red flags. In 2007, Microsoft Corp. researchers had published a technical paper warning that it contained a likely backdoor. The researchers homed in on something called the “Q value,” a large number in the algorithm used to help create encryption keys. At the time, NSA had a specific value it recommended. According to the researchers, whoever picked the value could calculate the secret contents of those keys and ultimately decrypt communications.

Nonetheless, the National Institute of Standards and Technology — a Department of Commerce agency that sets security requirements for federal computer systems — made the algorithm part of a federal cryptographic standard in 2008 at NSA’s direction, one of four that could be selected. Federal agencies and government contractors are required to follow NIST guidance, and the private sector often follows those standards.

Juniper was aware of concerns about a possible backdoor and also criticism that the algorithm was notoriously slow, according to the three employees present for or briefed about the meetings with the Pentagon. But because NIST had validated the algorithm, Juniper went forward with the proposal to satisfy a big customer, they said.

After Snowden’s disclosures in 2013 renewed concerns about the NSA algorithm, Juniper said in a security advisory that NetScreen products had two safeguards designed to prevent any exploitation of the vulnerability. However, after the company’s breach disclosure in 2015, independent researchers discovered that one of them failed, and the other was rendered ineffective by the hackers’ tampering.

Juniper wasn’t the only organization that used the algorithm.

OpenSSL, whose open-source encryption software is used by millions of websites, also incorporated it. A sponsor of the project requested its inclusion to meet NIST standards, Steve Marquess, a project manager, wrote in 2013. “We didn’t make [Dual Elliptic Curve] a default anywhere and I didn’t think anyone would be stupid enough to actually use it in a real-world context,” he wrote. Marquess didn’t identify the sponsor. He didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Microsoft Corp., Cisco Systems Inc. and other companies included it in their products as well, according to a database maintained by NIST. Dual Elliptic Curve often came in a package of encryption software that contained all four federally approved algorithms that were part of the same standard, and companies could decide whether or how to make them available to their customers.

Microsoft and Cisco made other algorithms the default choices. Cisco, in a blog post, acknowledged using third-party software that included Dual Elliptic Curve but said the algorithm was “not in use in any Cisco products.” A company representative declined further comment. Microsoft declined to comment.

Industry pioneer RSA Security received $10 million from the NSA in a deal that set Dual Elliptic Curve as the default in a package of encryption software that it licensed to other technology companies, Reuters reported in 2013. RSA and its owner, Symphony Technology Group, didn’t respond to messages from Bloomberg.

Juniper’s investigations of its breaches in 2012 and 2014 underestimated the hacking threats facing the company, mistakenly concluding that those incidents were attempts to steal trade secrets that had little effect, according to the two people involved in Juniper’s investigation and the internal document. The company reported the incidents to the FBI and the Defense Department but downplayed their significance to those agencies, based on its understanding of the intrusions at the time, the people said.

Juniper had missed an important clue.

In its 2012 probe, Juniper learned that the hackers had stolen a file containing NetScreen’s ScreenOS source code from an engineer’s computer. The company didn’t realize that the hackers returned a short time later, accessed a server where new versions of ScreenOS were prepared before being made available to customers and altered the code, according to the two people involved in the 2015 investigation and the document. The hackers’ tweak involved changing the Q value that the NSA algorithm used — the very same vulnerability that Microsoft researchers had identified years earlier. The hack allowed them to potentially bypass customers’ encryption and eavesdrop on their communications.

Juniper said in its December 2015 statement that it discovered the tampering during an internal code review. The company hired FireEye’s Mandiant division, a leader in digital forensics, to help investigate, according to the people and the document. The investigation concluded APT 5 was behind the attacks, the people said.

A spokesperson for Mandiant declined to comment.

Juniper revealed few specifics, but independent researchers filled in many details about what happened, identifying the illicit change to the Q value and the insertion of an unauthorized master password, disguised as debugging code. The hackers could use the password to gain access to NetScreen products.

Years later, Russian hackers were discovered using a similar method, inserting a backdoor in software updates from Austin, Texas-based SolarWinds Corp., an attack a Microsoft executive described as “the largest and most sophisticated attack the world has ever seen.” The attackers ultimately infiltrated nine U.S. agencies and at least 100 companies using the backdoor and other methods.

In the last year, a group suspected to be APT 5 has targeted VPN devices made by San Jose, California-based Pulse Secure LLC in attacks on dozens of companies and government agencies, according to FireEye. Daniel Spicer, chief security officer at Ivanti Inc., Pulse Secure’s parent company, said in a statement that a “highly sophisticated threat actor” was behind the attacks but declined to discuss the “attribution or motivation.” The company found no evidence that its source code had been modified. “A rigorous code review is just one of the steps we are taking to further bolster our security and protect our customers,” he said.

Because of their central role in telecommunications systems, Juniper products have been a longtime target for intelligence agencies, according to a 2011 document leaked by Snowden. It revealed that GCHQ — the British signals intelligence agency — developed secret exploits against at least 13 different models of NetScreen firewalls, with the knowledge of the NSA. Other classified NSA memos support cybersecurity experts’ suspicions about Dual Elliptic Curve, indicating the NSA created a backdoor and pushed the algorithm on NIST and other standards bodies. One NSA memo, cited in news articles based on the documents, called the effort a “challenge in finesse.”

Based on Snowden’s revelations, NIST revoked its support for the algorithm in 2014. In a statement, NIST said its decision was “due to the implications suggested by the Snowden revelations.” “Use and implementation of an encryption technology is rooted in trust, and NIST no longer had full trust in the base assumptions made for the security” of the NSA algorithm, the agency said.

While the Pentagon wouldn’t discuss specific questions about its relationship with Juniper, it responded to Bloomberg News with a general statement about its cybersecurity. “In light of increasingly frequent and complex cyber intrusion efforts by adversaries and non-state actors, the department is constantly applying mitigations, improving defenses, and closing vulnerabilities in our global information network,” said spokesman Russell Goemaere.

Juniper warned in a December 2015 technical bulletin that there was no way for customers to know if their NetScreen VPN traffic was intercepted and decrypted. And while any use of the illicit master password would have left a small record, Juniper cautioned that a skilled hacker could delete it and effectively eliminate “any reliable signature that that device had been compromised.”

For all the twists and lingering questions, cybersecurity experts and civil liberties defenders say the Juniper incident shows the perils of inserting backdoors — for spy agencies, the companies involved and their customers.

“Time and again, we’ve seen the government lose control of vulnerabilities,” said Jim Dempsey, a lecturer on cybersecurity at the University of California, Berkeley, School of Law. “The bigger lesson from the whole Juniper ordeal is that the government cannot control its vulnerabilities.” —With Michael Riley and Christopher Cannon

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.