Lebanon ended a 13-month wait for a new government Friday with the unveiling of a lineup that faces the daunting task of rescuing the country from economic meltdown.

A new cabinet was a condition for much-needed international assistance but its ability to deliver the required reforms remains to be seen and its announcement was met on the street with scepticism bordering on indifference.

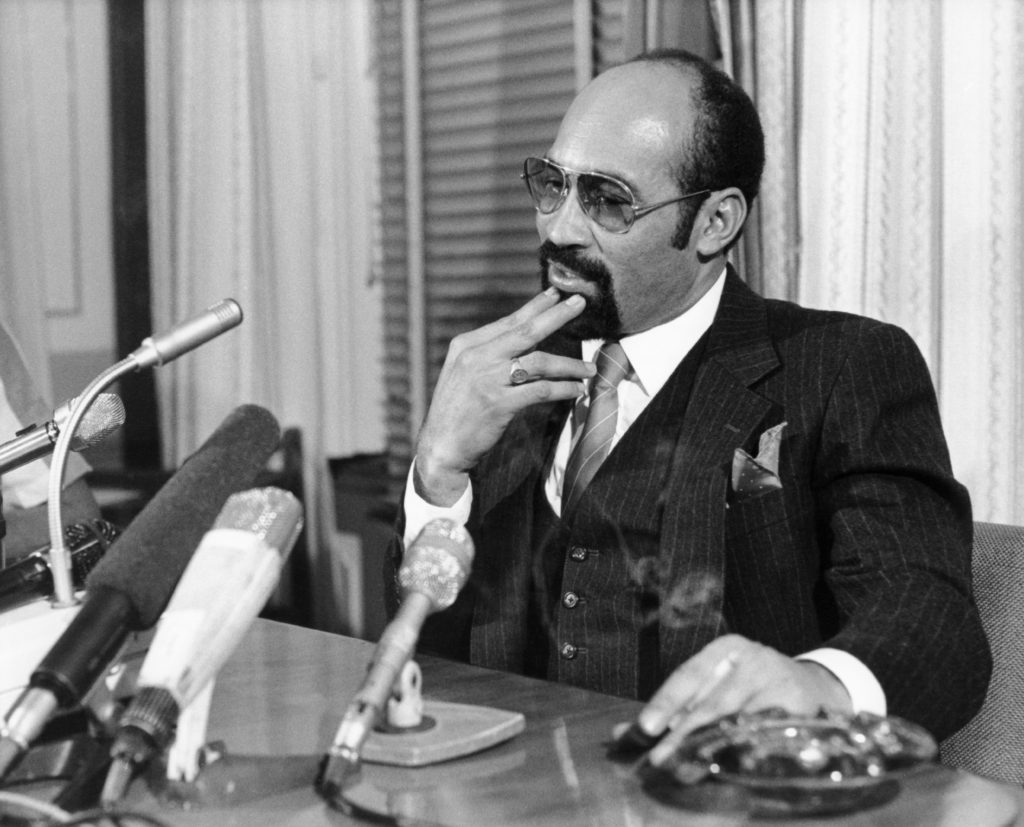

Billionaire Najib Mikati, Lebanon’s prime minister for the third time, made an emotional statement from the presidency vowing to leave no stone unturned in efforts to save the country from bankruptcy.

“We will make use of every second to call international bodies and ensure the basic everyday life needs,” he said, adding his government would also turn to Arab countries for help.

Mikati, who was designated as prime minister in July after his two predecessors failed to clinch an agreement on a new line-up, unveiled his list of ministers.

The newcomers include many technocrats but each minister was endorsed by one or several of the factions that have dominated Lebanese politics since the 1975-1990 civil war.

The country’s hereditary political barons have so far appeared impervious to international pressure, which intensified after a deadly explosion at Beirut port on August 4, 2020.

The blast, one of the world’s largest non-nuclear explosions, killed more 200 people and was widely blamed on government incompetence and corruption.

– ‘Same cooks’ –

Sami Nader, a Lebanese political analyst, argued there was little hope of a breakthrough if the dynamics that prevailed during the cabinet line-up negotiations remained in place.

“The continuation of quota politics and bickering over every reform and decision would mean no departure from what the caretaker government was able to do,” he said.

“It was the same cooks who formed this government,” he said.

Lebanon has been run by a caretaker government since August 10, 2020 when premier Hassan Diab and his cabinet resigned en masse following the port explosion that devastated swathes of the capital.

Notable in the 24-minister lineup was the inclusion of only one woman and the appointment as health minister of Firass Abiad, a doctor who rose to public prominence in the battle against the Covid-19 pandemic.

The appointment of George Kordahi, a star TV presenter known in the region as the host of the Arabic version of “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire”, in the government headed by Lebanon’s richest man drew heavy sarcasm on social media.

The state can no longer provide mains electricity to its citizens for more than a few hours a day, nor can it afford to buy the fuel needed to power generators.

The local currency has lost more than 90 percent of its value, entire segments of Lebanon’s six million inhabitants are sinking into poverty and those who can are emigrating by the thousands.

Very few of the international community’s demands for a broad programme of reforms have yet been met, hampering the disbursement of foreign assistance.

– Scepticism –

Further stalling the bankrupt state’s recapitalisation has been the government’s failure to engage the International Monetary Fund and discuss a fully-fledged rescue plan.

“The new government will have to prepare legislative elections and ensure they are held on time,” said Nader, the analyst.

Parliamentary polls are due next year, with many pinning their hopes on the ballot bringing in fresh blood but others doubtful a vote could yield game-changing results without a revamp of the electoral system.

“There is practically only one door on which to knock for this government and that is the International Monetary Fund’s, because there is no other way out of the crisis,” Nader said.

Western powers had lost patience with Lebanon in recent months and stopped short of welcoming the appointment this summer of Najib Mikati, seen by many as a symbol of a self-serving, sectarian and corrupt political class.

The European Union was quick to remind the new government of its priorities Friday, with the bloc’s foreign policy chief Josep Borrell emphasising the need to “implement long overdue reforms”.

On the streets of Beirut, the announcement of a new cabinet seemed to do little to lift the spirits of a population broken by one of the steepest economic declines the world has seen in decades.

“I am not optimistic, neither about this government nor about the whole country,” said Rony, a 18-year-old student. “I am willing to leave the country if I get a chance.”