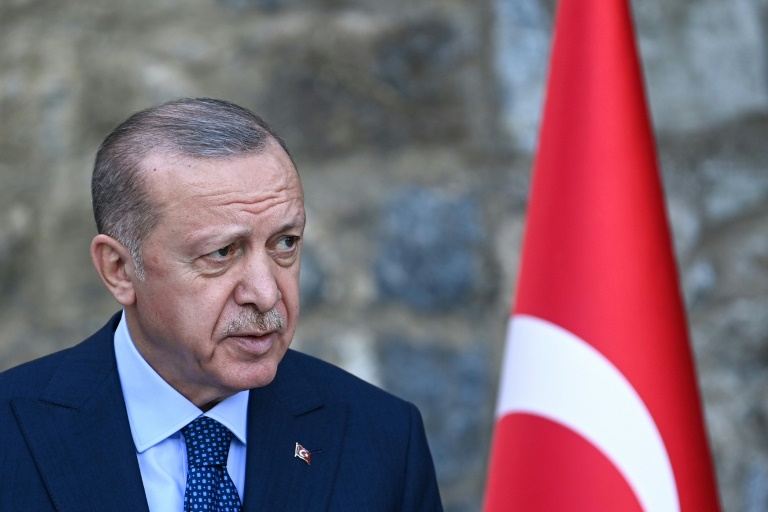

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan rowed back on Monday from his threat to expel 10 Western envoys over their joint statement of support for a jailed civil society leader.

The reversal came after the United States and several of the other concerned countries issued identical statements saying they respected a UN convention that required diplomats not to interfere in the host country’s domestic affairs.

Erdogan met his ultra-nationalist ruling coaltion partner and then chaired an hours-long cabinet meeting at which his ministers reportedly advised him about the economic dangers of escalating tensions with some of Turkey’s closest allies and trading partners.

He concluded the meeting by victoriously announcing in televised comments that the 10 ambassadors had learnt their lesson and “will be more careful now”.

“Our intention is absolutely not to create a crisis but to protect our honour, our pride, our sovereign rights,” Erdogan said.

The new Western statement “shows they have taken a step back from the slander against our country”, Erdogan said.

The lira recovered from a historic low and was trading up almost half a percent against the dollar on relief that Turkey and the West had stepped back from the brink of the most serious diplomatic crisis of Erdogan’s 19-year rule.

Erdogan had originally threatened the ambassadors on Thursday and then doubled down — pronouncing the 10 envoys “persona non grata” — in televised comments on Saturday.

Diplomats said the expulsions would have been unprecedented in relations between fellow NATO member states.

– ‘Skipping confrontation’ –

The diplomatic standoff began when the 10 embassies — including those of Germany and France — issued an unusual statement last Monday calling for the “just and speedy” resolution of the legal case against jailed philanthropist Osman Kavala.

The 64-year-old civil society leader and businessman has been in jail without a conviction for four years.

Supporters view Kavala as an innocent symbol of Erdogan’s growing intolerance of political dissent since surviving a failed military putsch in 2016.

But Erdogan accuses Kavala of financing a wave of 2013 anti-government protests and then playing a role in the coup attempt.

Kavala’s case could prompt the Council of Europe human rights watchdog to launch its first disciplinary hearings against Turkey at a four-day meeting ending on December 2.

The ambassadors said Kavala’s case “cast a shadow over respect for democracy, the rule of law and transparency in the Turkish judiciary system”.

Yet analysts pointed out that several European powers — including fellow NATO member Britain — refrained from joining the Western call for Kavala’s release.

“The conspicuous absence of the UK, Spain, and Italy… is telling, pointing at the emergence of a sub-group within the Western family of nations adept at skipping confrontation with Ankara,” political analyst Soner Cagaptay wrote.

– Financial turmoil –

Erdogan’s rule as prime minister and president has been punctuated by a series of crises and then rapprochements with the West.

The Turkish leader has spent much of the past year trying to mend relations with Arab world rivals and long-standing European competitors such as Greece.

But analysts said Erdogan has been disappointed by his attempts to win over US President Joe Biden — an outspoken critic of Ankara’s rights record who refused to grant the Turkish leader a personal meeting on the sidelines of a UN summit last month.

Erdogan appeared to reverse course this month by threatening to launch a new military campaign in Syria and then orchestrating changes at the central bank that infuriated investors and saw the lira accelerate its record slide.

Turkey’s financial problems have been accompanied by an unusual spike in dissent from the country’s business community.

Main opposition leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu accused Erdogan of trying to create an artificial diplomatic crisis that he could then blame for Turkey’s economic woes, ahead of a general election due by June 2023.