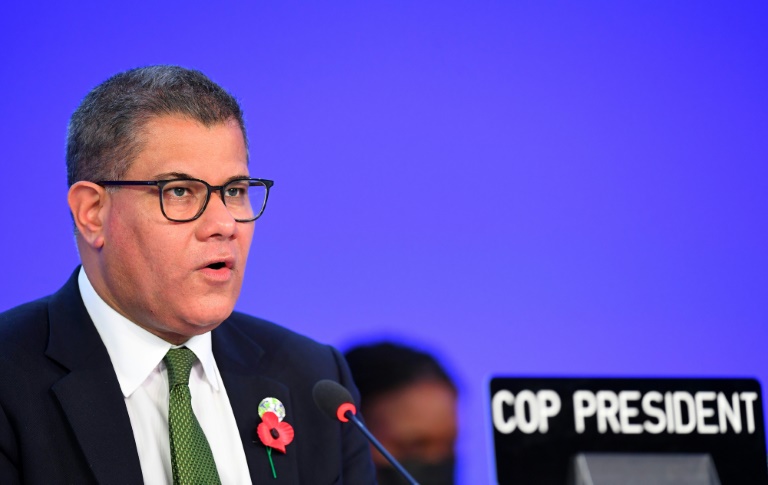

Alok Sharma was hardly a household name in Britain, let alone the rest of the world, when appointed to lead the UN climate talks now reaching a climax in Glasgow.

But with the planet’s future at stake, the COP26 president has had to emerge from the shadows to stand in a blindingly bright spotlight over the past fortnight, trying to reconcile seemingly irreconcilable demands.

Reflecting on his own role, the self-effacing former UK business secretary said on Thursday: “People sometimes describe me as ‘No Drama Sharma’.”

The nickname is modelled on the former US president, Barack Obama. But Sharma will have been hoping for a better outcome than “No Drama Obama”.

Then in his first year in the White House, the inexperienced Obama suffered an infamous bust-up with the Chinese at the 2009 COP in Copenhagen.

Sharma certainly lacks the vaulting oratory of Obama or his own boss, Prime Minister Boris Johnson, who appointed him to steer the COP26 process alongside the UN in February 2020.

That came just as the coronavirus pandemic began to sweep the world, but the 54-year-old politician has nonetheless kept up a gruelling globetrotting schedule in the months leading up to Glasgow.

Sharma has sought to forge personal relations with smaller island states but also with more influential economies by visiting China and his native country of India — two of the biggest holdouts against an ambitious deal.

He has won some praise from delegates for his balanced leadership.

Yet all along, Sharma has been dogged by criticism that Johnson should have appointed a bigger hitter to the pivotal climate job.

“I think Alok Sharma has done fine, but I think the wider UK government has been at fault because I think they didn’t embrace the seriousness of the degree of difficulty early enough,” Britain’s former Labour leader Ed Miliband told AFP.

Taking aim at Johnson directly, he said: “You can’t compensate in two weeks for not having done the work for two years.”

– Corporate to climate –

Sharma initially combined the role of COP26 president with the position of Johnson’s cabinet secretary for business, energy and industrial strategy.

The dual-hatted approach attracted criticism that Johnson was not taking the COP process seriously enough, and Sharma eventually took on that role full-time in January this year.

Sharma was born in the Taj Mahal city of Agra in 1967 and his parents moved to Reading, a commuter-belt town west of London, five years later.

Like his better known colleague, finance minister Rishi Sunak, Sharma has taken the MPs’ oath of allegiance over the Hindu Bhagavad Gita.

Johnny Luk, a Conservative activist of Chinese heritage, recounted how he “received quite a lot of racial abuse” when he stood unsuccessfully for parliament in 2019.

“Alok reached out personally to express his support to me, which I care about deeply,” he told The Daily Telegraph when Sharma was made COP26 president.

“He is one of the nicest guys I know in politics, he is razor sharp, he cares about specific issues, not just soundbites,” Luk added.

There was little to suggest a future role as climate guru in Sharma’s path from university at Salford, in northwest England, to his training as an accountant and then jobs in corporate finance.

Urged by his Swedish wife to consider a career in politics, he became an MP for Johnson’s Conservatives in 2010, representing a seat in affluent Reading.

Sharma held a variety of junior government positions before being given the cabinet-level job of international development minister when Johnson took office in July 2019.

He was one of the few “Remainer” politicians kept on by Johnson, after campaigning for Britain to stay in the EU, but was judged as a safe pair of hands and went on to stay true to the prime minister’s hardline vision of Brexit.