By Chibuike Oguh

(Reuters) – TPG’s top dealmakers will force the buyout firm to pay them the cash value of tax savings it expects to receive, currently estimated to be worth $1.44 billion, in the years following its initial public offering (IPO), a regulatory filing shows.

The practice has been popular with buyout firms going public since Blackstone Inc deployed it in its IPO in 2007. Private equity firms argue the arrangement is justified in rewarding their partners.

Critics say it strips their public shareholders of value that should have gone to them.

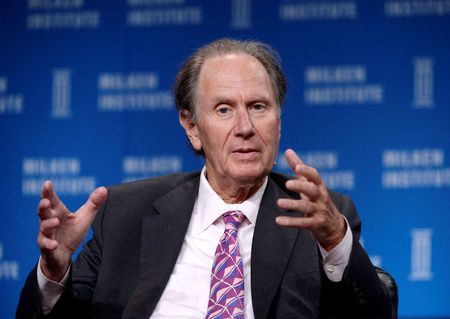

Robert Willens, a tax expert and professor of finance at Columbia Business School, said there was a risk that IPO investors may not fully appreciate how much value in the private equity firm is being transferred to its founders because of the complexity of the process involved.

“Public investors could be overpaying for the stock, it is hard for them to understand the implications,” Willens said.

A TPG spokesperson declined to comment.

The tax benefits TPG will enjoy stem from its reorganization as it goes public.

In acquiring the interests of its founders in its operating partnership, TPG expects to see a step-up in its tax basis, allowing it to take depreciation and amortization deductions that reduce its taxable income, the filing shows.

TPG has entered into a “tax receivable agreement” with its founders to pay them 85% of the cash value of these tax savings, according to the filing.

The Fort Worth, Texas-based firm said that value, currently pegged at $1.44 billion, “may materially differ” by the time the tax savings will be realized. It added that it expects the payments it will have to make under the agreement to be “substantial” and that they could have a “material negative effect” on its cash position.

TPG disclosed on Tuesday it expects to be worth $9.5 billion in its IPO, so the tax receivable agreement would transfer an estimated 15% of that value to TPG’s top dealmakers, primarily founders David Bonderman and Jim Coulter and Chief Executive Jon Winkelried.

Bonderman and Coulter are already billionaires, and the estimated $1.44 billion payout would boost their fortunes further. Forbes pegs Bonderman’s and Coulter’s net worth at $4.5 billion and $2.6 billion, respectively.

If it does not have enough money to make the tax receivable agreements payments in time, TPG will be charged interest equal to the one-year LIBOR rate plus 5%, the filing shows. And if a change of control occurs, such as its founders giving up their dual-class shares, TPG will owe them the remaining estimated value of the tax savings.

This happened in the last two years when the founders of peers KKR & Co Inc, Apollo Global Management Inc and Carlyle Group Inc gave up voting control by turning the firms into corporations with a single class of stock.

This triggered a $560 million payment for KKR’s founders under their tax receivable agreement, which the New York-based firm said it would pay in the form of stock.

LAWMAKER SCRUTINY

Apollo’s founders and executives secured a payout of at least $584 million over four years in similar fashion under its tax receivable agreement when the firm announced last year it would eliminate its dual-class structure, regulatory filings show.

The executives elected to receive the payout in cash rather than Apollo stock.

A source familiar with the matter said the payout was worth only half the value of the accrued tax benefits owed to the founders, who agreed to forego the other half in the interest of Apollo’s shareholders.

Carlyle was the first among the major publicly listed private equity firms to get rid of special voting rights for its executives in 2019.

The change triggered a $346 million cash payout over five years for the Carlyle executives under its tax receivable agreement, regulatory filings show.

The use of tax receivable agreements by private equity firms attracted U.S.

lawmaker scrutiny in 2007, when Blackstone disclosed in its IPO filings that its executives could receive tax benefits totaling $863.7 million over the next 15 years under the arrangement.

However, U.S.

Congress never passed into law proposed legislation that would have taxed payments made through tax receivable agreements as ordinary income. The use of tax receivable agreements expanded in popularity, and some private equity firms used them to extract value from portfolio companies they took public.

“Private equity firms use expensive tax lawyers a lot for their portfolio companies.

It is therefore not surprising that they use convoluted tax tricks to their direct benefit as well,” said Ludovic Phalippou, a finance professor at the University of Oxford’s Said Business School.

(Reporting by Chibuike Oguh in New York; Editing by Greg Roumeliotis and Matthew Lewis)