(Bloomberg) — Former top prosecutor Yoon Suk-yeol won election as South Korea’s president, returning the conservative opposition to power after five years and signaling a hawkish turn in the country’s relations with China and North Korea.

The political newcomer edged out former Gyeonggi Governor Lee Jae-myung by less than one percentage point, the country’s closest presidential contest ever. Yoon, 61, resigned from President Moon Jae-in’s government last year after a falling out over investigations into the leader’s associates, and the election campaign was dominated by party infighting, ethical scandals and emotional debates over age and gender divides in Asia’s fourth-largest economy.

“The race is over and now we need to be united as one for the sake of the people and the country,” Yoon told supporters and party officials early Thursday morning. Yoon planned to visit Seoul National Cemetery at 10 a.m. and hold a briefing at 11 a.m. at the National Assembly.

Yoon secured 48.6% of the vote, compared with Lee’s 47.8%. “All responsibility rests solely with me,” Lee, 57, said after conceding the loss and congratulating Yoon.

The new president has signaled a tougher stance toward neighbors China and North Korea, but will face daunting domestic challenges after he takes office May 10. Moon’s party retains a supermajority in parliament, limiting Yoon’s options to energy, housing and diplomatic policies being implemented largely by executive orders until at least the next elections in 2024, wrote Goldman Sachs Group Inc. analysts including Goohoon Kwon.

“With the conservative opposition victory, we expect a turn to an incrementally less expansionary fiscal policy combined with relatively less hawkish monetary policy,” they wrote. “The Yoon presidency is also likely to press ahead with pro-business deregulation and housing supply measures.”

South Korean shares opened higher, with the benchmark Kospi index up about 2% at the start of trade Thursday. Korean markets outperformed the rest of Asia’s main stock markets.

Yoon’s reputation as a dogged investigator won him a following and he was picked by Moon to help clean up government after the impeachment, ouster and conviction of former conservative president Park Geun-hye. Ties soured after Yoon’s probes included members of the current government and led to the resignations of two of Moon’s justice ministers.

The conservative bloc, adopting the populist-sounding name People Power Party, recruited the outsider to run as its standard bearer despite internal opposition, in part to clean up its image. While Yoon has often veered from the party script, he has embraced the conservatives’ traditional support for South Korea’s alliance with the U.S. and its wariness of ties with China and North Korea.

Yoon said he would back a preemptive strike if Pyongyang posed an immediate threat and called for a new deployment of a U.S.-made missile interceptor system known as THAAD. China banned sales of group tour packages and appearances of Korean celebrities on television shows in retaliation for Seoul’s deployment of the U.S.-led missile shield system about six years ago.

“The expectation is that we will see South Korea be more unequivocal toward the alliance,” said Soo Kim, a policy analyst at Rand Corp. who previously worked at the Central Intelligence Agency. “I don’t think this resetting of South Korean foreign policy is going to happen overnight,” she told Bloomberg Television before the vote.

Moon had made improving ties with North Korea a central focus of his presidency, sometimes prompting friction with Washington. He saw relations sour with Tokyo, while courting Beijing’s support.

Cheon Seong-whun, a former security strategy secretary under Park, said Yoon would likely to take a bigger role in U.S.-led strategic initiatives. He would “more actively participate in sanctions against Russia and North Korea,” as well as in “naval drills in the Indo-Pacific theater,” Cheon said.

“Although that does not mean South Korea will be in lockstep with the U.S. on all issues, that will not please China,” said Naoko Aoki, a research associate at the University of Maryland’s Center for International and Security Studies. “He is more willing to treat China as a threat.”

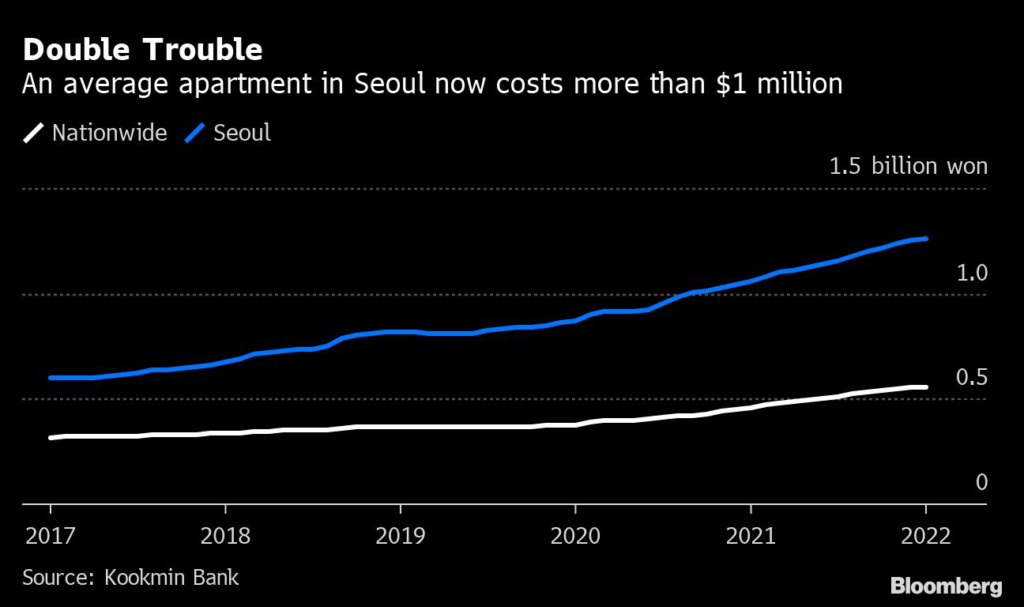

Housing prices have doubled in urban centers such as Seoul during the Moon’s term, while wages have failed to keep pace. That has made home ownership unaffordable for many families over the long term, while inflation unexpectedly accelerated in February. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine suggests there will be little respite for rising prices soon.

Yoon “shows a great willingness to implement market-friendly policies,” said Hong Chunuk, chief executive of Richgo Investment in Seoul. “We can expect the government to play a role of a fair judge.”

On the campaign trail, Yoon promised to narrow income disparity and implement a 100-day emergency rescue plan for a Covid-hit economy that would provide a quick and hefty financial injection. He also stoked divisions by pledging to shut down the Gender Equality Ministry — despite South Korea having one of the largest gender-based pay gaps in the developed world.

Lee, a former factory worker who later became a civil rights lawyer, had pushed to make the country Asia’s first to introduce universal basic income. The negative tenor of the campaign turned off a lot of voters and increased political acrimony.

“Yoon’s immediate challenge will be dealing with a deeply divided country that largely either detests him or voted for him only because they detested Lee even more,” said Duyeon Kim, an adjunct senior fellow in Seoul at the Center for a New American Security.

(Updates with stock market open in seventh paragraph.)

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.