(Bloomberg) — On the corner of 42nd Street and Sixth Avenue in Manhattan, Pete Sikora gazes up at a glass-enclosed tower that twists with unexpected grace as it rises 51 stories into the sky. Sikora is director of climate and inequality campaigns at New York Communities for Change, an activist organization. On this breezy September day, however, he’s posing as an energy specialist in the hopes of gathering intelligence about the skyscraper, One Bryant Park, also known as the Bank of America Tower in honor of its primary tenant.

Tall and bespectacled with the mischievous air of a professional agitator, Sikora says he’s examined city data showing One Bryant Park’s carbon emissions and the amount seems high to him. Could the skyscraper have a secret nuclear fusion lab inside? he asks. Or the futuristic technology of Lex Luthor’s tower in the Superman comics he read as a boy? He’s joking, but not entirely. He sees Douglas Durst, chairman of the family-run real estate company that owns One Bryant Park, as someone intent on obscuring the reasons for what Sikora describes as its unacceptable carbon count. “They’re on the verge of getting the reputation of a huge polluter,” Sikora says. “What are they thinking?”

He’s not likely to get past the heavy security presence in the lobby. So Sikora seeks answers from people leaving the building. His first targets: two men who look like bankers. “Hi, I work in energy efficiency,” Sikora says. “What’s going on in there?”

“Well, they’re not mining Bitcoin,” one of the bankers tells Sikora, while the other ponders his phone. The chattier financier says he hasn’t noticed anything odd inside. It’s actually quite nice, he says.

Sikora steps closer to the entrance and approaches another man exiting the building. The guy identifies himself as a contractor and wants to be helpful, but he only has so much information. “Really, I don’t know,” he says. “But you’ve got a lot of computers, so there’s a lot of something going on there.”

Others treat Sikora frostily. “This is the best energy building in Manhattan,” one man says, raising his arm to ward off the activist.

Sikora is among the most vigorous defenders of New York City’s landmark law capping carbon emissions in buildings. Most people don’t think of their dwellings and workplaces as sources of greenhouse gases, but they often are. Buildings account for more than a quarter of the world’s energy-related emissions, according to the United Nations. In cities, where there is so much brick and mortar, to say nothing of steel and glass, they can be responsible for more than two-thirds of the emissions total.

Naturally, cities around the world are taking steps to address the problem. Oslo and Stockholm are retooling the underground systems that warm their buildings to run on cleaner energy. In tropical Singapore, developers are encouraged to design buildings with so much greenery they appear to have sprouted from Avatar.

In 2019, New York City passed Local Law 97, a sweeping measure establishing emissions caps for almost 50,000 of its largest buildings, including the headquarters of some of the world’s largest financial companies. The owners of an estimated 20% of these skyscrapers, hotels, and apartment houses will likely face fines in 2024 when the law goes into effect, because the emissions of their properties will exceed the caps. The proprietors of many more could be in a similar quandary in 2030, when the caps will be lowered by 40%. “It’s the largest emissions reduction policy—not just in the history of this city, but any city in the world,” says former New York City Council member Costa Constantinides, the law’s proud sponsor.

With characteristic New York brio, its advocates say that urban areas throughout the U.S. can—and should—adopt the law. In October, Boston became the first city to pass its own version of Local Law 97, and Mark Chambers, who helped shepherd the law’s passage as New York’s sustainability chief before becoming the Biden administration’s senior director for building emissions, is nudging others to do the same. “We are actively encouraging more cities to evaluate this as a possible policy pathway to building decarbonization,” he says.

Whether Local Law 97 itself will be as transformative as its proponents predict is in doubt, though. Many of the people responsible for passing it—former New York Mayor Bill de Blasio and its city council backers—have departed. Instead, the law will go into effect under Eric Adams, the city’s new mayor, who’s more sympathetic to the real estate industry and its concerns about the punitive nature and ultimate effectiveness of the law.

At the center of the debate is One Bryant Park. The $1.8 billion tower was hailed as the city’s greenest when the Dursts completed it in 2010. Al Gore snipped the ribbon at its opening ceremony, calling the skyscraper “a fantastic piece of work.” Rick Fedrizzi, then chief executive officer of the U.S. Green Building Council, bestowed his organization’s highest honor on it: LEED Platinum certification. “This is probably the most important building that has been built in America in the last several decades,” he said.

Under Local Law 97, One Bryant Park no longer appears as lustrous. The Dursts anticipate that it will overshoot its cap by an estimated 50% in 2024, and they’re contemplating an annual fine of $2.4 million unless they can dramatically alter its energy use. For some of the law’s most enthusiastic supporters, wealthy owners of such “dirty buildings” are getting what they deserve. For others, like Stuart Brodsky, director of New York University’s Center for the Sustainable Built Environment, the notion that the Dursts are being so labeled is evidence of something very different. “It’s a deeply flawed law,” he says.

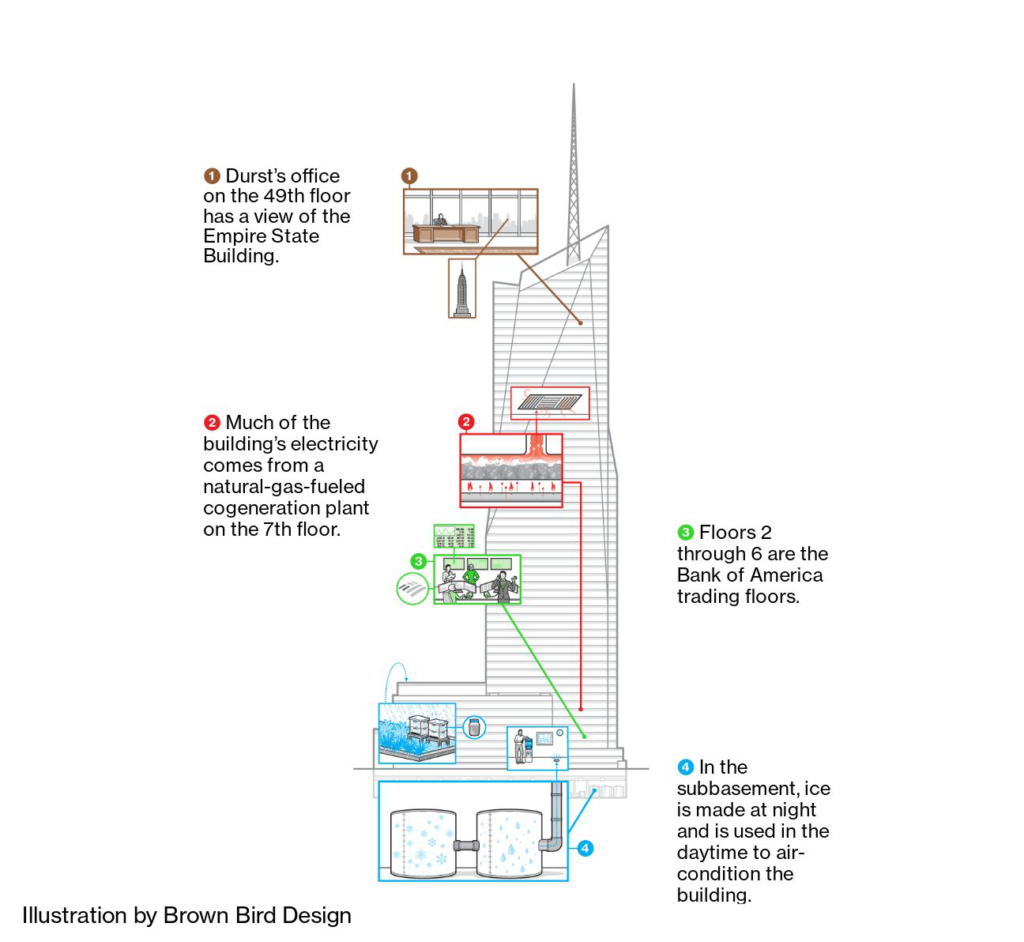

Just after 1 p.m., Douglas Durst shuffles into a conference room on the 49th floor of One Bryant Park, where his company has its office. He’s wearing a black pinstriped suit and a matching face mask. He prefers running shoes to Oxfords; the ones he has on today are bright green. He settles into a chair in front of a window with a glorious view of the Empire State Building, which One Bryant Park approaches in height.

At 77, Durst is one of the great characters of New York real estate, a terse conversationalist with a mordant sense of humor. Far from being elusive, he’s happy to disclose the inner workings of his building. He says there’s no mystery: Bank of America Corp. has five trading floors operating around the clock, packed with employees monitoring multiple computers at their desks. “A densely occupied building like this is going to consume more electricity than a lightly occupied building,” he says. To hear Durst tell it, Local Law 97 doesn’t distinguish between the two. “So a building that’s vacant is going to get a better score than a fully occupied building,” he continues. “It makes absolutely no sense whatsoever. That’s the problem in a nutshell.”

Durst says he can’t tell Bank of America to use less power: His family’s long-term lease with the company forbids it. The building has an extensive air filtration system that uses lots of electricity, but he’s not running it at less than full blast because it’s healthier for the occupants, pandemic or no pandemic. “I’ve always said, well, if we made everybody walk up, we could do away with elevators,” Durst says. “That’s not going to happen either.” (A spokesperson for Bank of America says it has significantly reduced its energy usage in the building over the years.)

What galls Durst is what he describes as the law’s failure to take into account the steps his family has taken to use energy wisely. “We’ve spent the last 40 years—40 years, time flies—making our buildings as efficient as possible,” he says. He notes he and his kin would have been better off doing none of that and saving their money to comply with Local Law 97.

The Durst Organization traces its roots to 1915, when Joseph Durst, an Austrian immigrant and a tailor by trade, started acquiring property in the city. His son Seymour, leader of the family’s second generation, spent decades patiently assembling development sites within walking distance of Grand Central Terminal on which the family could erect high-rises. Seymour, known for his skepticism about government economic policies, funded the famous Times Square clock that measures the escalating national debt.

Seymour’s son Douglas was a maverick of a different sort. A child of the 1960s, he was an ardent environmentalist out to prove that a skyscraper could be profitable and sustainable, which made him an outlier at the time in New York. “He’s not only the real item,” says Mary Ann Tighe, head of the New York region for the real estate firm CBRE. “He’s the original item.” (Douglas’s older brother, Robert, the subject of an HBO documentary, was convicted last year of the decades-old murder of a friend. He died in January.)

When Douglas and his cousin Jody took over the family business in the ’90s, the first tower to soar under their leadership raised eyebrows. Sustainability mavens extolled the 48-story skyscraper, then known as 4 Times Square, for its inclusion of natural-gas-powered fuel cells and the integration of solar panels into its facade. Completed in 1999, 4 Times Square, which housed the headquarters of Condé Nast for many years, was “one of the first environmentally responsible skyscrapers to be constructed in the United States,” according to the Urban Land Institute. Durst prefers to think of it as the first.

The Dursts tried to top themselves at One Bryant Park, which rose next door. Most of the new building’s electricity would be provided by a natural gas-fueled cogeneration plant that would not only keep the lights on in the building: The heat from the combustion process would be converted into additional power to operate the heating and air-conditioning systems. Then again, the plant would still be burning fossil fuel.

One Bryant Park would be cooled with water frozen in a subbasement. The Dursts needed to tap the city’s electrical grid to produce the ice. But they did it at night, when there was less demand on the grid. During the day, Durst says, Consolidated Edison Co., the city’s main electricity provider, was likely to draw on dirtier plants to keep New Yorkers comfortable in sultrier months.

The family also cultivated green roofs at One Bryant Park, and when the plants didn’t pollinate the Dursts added beehives. The vegetation flourished, and there was another benefit. Durst rises from the table and makes a call. An employee soon appears with a small jar of honey in a purple gift bag.

Perhaps inevitably, what was bleeding edge in green buildings as recently as a decade ago soon came to be seen as less so. Some complained that the LEED process smacked of greenwashing, awarding points not just for energy efficiency but also for seemingly superfluous items like environmentally acceptable carpets in buildings such as One Bryant Park. (A spokesperson for the U.S. Green Building Council defended its certification procedure but declined to comment on this building.)

As the climate crisis worsened, environmentalists started agitating for building owners to abandon fossil fuels altogether and fully electrify their real estate. How else, they argued, would cities like New York meet their goal of having net-zero emissions by 2050? The Durst Organization took part in an effort led by the nonprofit Urban Green Council calling for New York’s building owners to do their part by ratcheting down their energy use.

Cheered on by environmental justice activists, Mayor de Blasio and the New York City Council chose a different path: mandatory carbon reductions for bigger buildings. And greener real estate wasn’t the law’s sole objective. Supporters hoped the stringent caps, backed by the threat of fines, would force property owners to embark on a retrofitting spree, creating 26,000 jobs and easing the city’s inequality problem.

Durst became Local Law 97’s most outspoken critic. To go fossil-fuel-free at One Bryant Park, he’d have to scrap his cogeneration plant, and that makes no sense to him. “They want to replace all these systems, even though the useful life of the equipment would be another 20 to 30 years,” he says. He adds that natural gas shouldn’t be abandoned too hastily in the rush to electrify real estate, warning, as others do in his industry, about what might happen in a wintry blackout. “The city would simply have to close up,” he says. “Buildings would freeze. It would be a disaster.”

And even if he were to go all electric at One Bryant Park, Durst laments, he’d just be plugging into a dirtier, less efficient fuel source. The city’s electrical grid became almost entirely fossil-fuel-dependent last year after the closing of two nuclear plants responsible for 25% of its supply, according to Urban Green Council. There are wind farms in the works off the shore of Long Island that will eventually provide the city with green energy, but no turbines are rotating yet. “It’ll get here,” Durst sighs, “but certainly not by 2024.” (State officials say the first of these projects could begin operating as soon as 2023 with four more starting up over the next six years.)

Durst fears his family will have little choice but to pay the full fine. “It’s the progressives,” he says. “Is that what we call them? They want to punish the landlords. The bizarre thing about the law is that the fines go into the city’s operating budget. It doesn’t do anything for energy usage.”

“If this is a carbon tax, then call it a carbon tax,” says John Gilbert, former chief operating officer of Rudin Management Co., another of the city’s family-owned real estate dynasties. “But if it’s simply penalizing property owners, who don’t control their own destiny, then that’s just a bad public policy.” The law’s supporters say the owners, some of whom are self-identifying billionaires, such as former President Donald Trump, should stop griping and start retrofitting. “They need to do what’s right here, not try and evade the law,” New York Communities for Change’s Sikora says.

With a law so sweeping, many details still need to be sorted out before it goes into effect, a process being overseen by Gina Bocra, chief sustainability officer in the New York City Department of Buildings. She’s also chairperson of the city’s Local Law 97 Advisory Board. Bocra has had a look inside One Bryant Park, and she was impressed. “They have some really, really great equipment for managing their energy impact during peak periods,” she says. “That’s the type of thing we need all building owners to be doing.”

Bocra says she’s not unsympathetic to the complaints of Durst and other property owners about the law. She says the same is true of her board, which is considering making allowances for buildings such as One Bryant Park that time their energy use. It’s also examining whether owners of buildings whose excessive emissions are related to “high-density occupancy” should be penalized less severely. “Certain use types, we know, are more energy intensive,” Bocra says. “Trading floors, financial types of spaces, they don’t behave like regular office space. They’re different.”

These items, however, are still being debated by the board. One of its most vocal members happens to be Sikora, hardly a booster of One Bryant Park. Standing outside, he praises its off-peak energy use. But after his conversations with people exiting the building, he doubts it should qualify for a density break. Five trading floors? He’s unmoved, and he says the Dursts should expect similar skepticism if they try to make such a case to the Department of Buildings, which they plan to do. “They’re not going to get that if it’s just phony,” Sikora says of the Dursts. “The people who are implementing the law are real professionals. They’re not just going to take phony baloney.”

When I return to One Bryant Park for a tour, Durst is dressed much as he was on my previous visit, except this time his pinstriped suit is gray. His mask is a matching shade, as are his sneakers. I tell him about Bocra’s praise, but Durst won’t accept accolades from an official involved in carrying out Local Law 97. “It’s going to cost us two and a half million a year,” he says. “Is that what she means? Because she can get some money out of it?”

We board an elevator and descend 77 feet below street level, where the ice-making process happens. There are 42 silver storage tanks, each containing 8,450 gallons of frozen water. The liquid is now being used to chill a separate supply of water that’s circulated through One Bryant Park to provide air conditioning. As this water starts to warm up, its heat is absorbed by recycled rainwater stored near the tower’s summit. If the office tower hadn’t been configured to capture it, the rainwater might have been dumped into the city’s overburdened sewer system. Years ago, Durst says, tenants didn’t understand why his family was doing such things with its skyscrapers. “They all know now,” he says.

Durst doubts his family will be spared Local Law 97’s penalties in 2024, but in the longer term he has reason to be hopeful. A month later, New York Governor Kathy Hochul announces the state has finalized contracts with two consortia planning to build transmission lines through which clean power will flow into the city from upstate and Canada. Not only is the deal likely to make the city’s grid greener; a state official says it could eventually make renewable energy credits available that property owners with high emissions could purchase to more easily comply with the law. Among those contributing glowing comments to Hochul’s press release: Douglas Durst.

Then there’s Mayor Adams. He’s expressed concern through a spokesperson that the law unfairly punishes efficient buildings. It sounds a lot like Durst’s critique. (The spokesperson declined to comment further to Bloomberg Green.) Adams isn’t the only one with qualms. “We’re lucky we have real estate developers who are willing to experiment with innovative ways of making buildings cleaner and more energy-efficient,” says NYU’s Brodsky. “If the sustainablity community wants to attack them for that, then there won’t be any developers who step up and try new things.”

Supporters of Local Law 97, like Sikora, vow to fight any attempts to alter it. In early March, he was outside One Bryant Park, this time with more protesters. Some Durst employees took him inside for a tour. It didn’t change Sikora’s mind.

Still, Durst sounds mildly optimistic. “What we’re hoping is that common sense prevails,” he says. “We’ll see.” Then again, the Dursts have been in business for more than a century. Politicians come and go; the family abides. Douglas and Jody are grooming the fourth generation to take over. Eventually, they’ll do some refurbishments. With the sea level rising around Manhattan, they can’t afford not to. But they’ll do it according to their schedule. Not somebody else’s.

(Updates 28th paragraph with additional information about wind farms. A previous version corrected details about the cogeneration plant at One Bryant Park due to an error by the Durst Organization in the 21st paragraph and the illustration.)

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.