(Bloomberg) — Citadel Securities LP was thrust into the spotlight in 2021, with day traders, lawmakers and regulators all scrutinizing the firm at the center of one of the U.S. stock market’s wildest periods. They’re about to learn that amid the uproar, the financial giant had its best year ever.

Billionaire Ken Griffin’s stock-trading powerhouse posted record revenue of $7 billion, as frenzied bouts of volatility helped drive up earnings. The figure, disclosed by people familiar with the matter who declined to be named discussing private information, topped the firm’s previous record of $6.7 billion in 2020, when the pandemic upended global markets.

Inside Citadel Securities, the haul is reason to celebrate. But it also highlights an emerging problem that senior executives seem acutely aware of — the bigger it gets, the bigger the target on its back.

With ambitions to grow even more, the company is starting to crack open its previously sealed doors to respond to its naysayers. In over a half dozen interviews, top managers addressed concerns that the firm is too dominant, discussed rumors of a possible initial public offering and hinted at plans to expand into businesses that have long been controlled by Wall Street banks.

“You get to a point where staying under the radar is no longer an option,” Chief Executive Officer Peng Zhao, 40, said from the company’s Chicago headquarters. “We want to be able to tell our own story, rather than having the story told about us.”

There are many seeking to frame the Citadel Securities narrative. U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission Chair Gary Gensler has questioned whether retail investors are being disadvantaged because equities trading is so concentrated among Citadel Securities and a small group of rivals. After the firm’s starring role in last year’s meme-stock frenzy, Griffin was hauled in front of Congress where one lawmaker likened Citadel Securities to a casino and later, another called it a shark. Just this month, comedian Jon Stewart threw some jabs on his new streaming show.

As a market maker, Citadel Securities facilitates trading by stepping in as a buyer or seller, earning tiny profits on price differences often within milliseconds. The business Griffin built from a small group adjacent to his hedge fund has expanded into one of the biggest trading houses in the world, handling about 40% of all U.S. retail trading volume and one in every four U.S. equities trades.

But even that isn’t enough for the ultra-ambitious Griffin, who is said to frequently check that Citadel Securities remains atop a ranking of market-making rivals like Virtu Financial Inc. and Susquehanna International Group, people familiar with the matter said. Griffin, with a net worth topping $30 billion, has a reputation for driving an intense, competitive culture. Zhao recalls how he was in his second year at the firm as a low-level quant in 2007 when Griffin drafted him to help build out mortgage models. What Zhao thought would be a few hours of work turned into a three-month sprint with Griffin physically moving into Zhao’s office.

“For many weeks Ken was looking over my shoulder, hovering above my keyboard, putting out statistical analysis, models and graphs,” said Zhao, a child math prodigy with a PhD in statistics from the University of California, Berkeley, speaking in his first ever in-person interview with a news organization.

Now, the company plans to add business in Europe and Asia, and wants to be a major liquidity provider in the exploding cryptocurrency market, a goal underscored by the $1.15 billion it recently received from two prominent Silicon Valley investors. That deal, valuing the firm at $22 billion, could also herald an initial public offering — propelling it onto the very stock markets it now dominates.

As a designated market maker, the firm handles trades for more than 60% of listed names on the New York Stock Exchange, where employees still occupy two booths on the trading floor, decked in royal blue jackets with Citadel Securities logos.

In interviews throughout February, Citadel Securities executives didn’t dismiss an IPO though said a listing wasn’t on its immediate agenda. Still, the step would help it build on its expansion particularly with institutional clients who typically route their orders through Wall Street banks, Chief Operating Officer Matt Culek said.

The firm has already signed 250 clients to the institutional equity options business it launched in 2020 under former Deutsche Bank AG executives Dave Silber and Jason Roelke. Customer volumes in the group soared 90% in the fourth quarter from a year earlier.

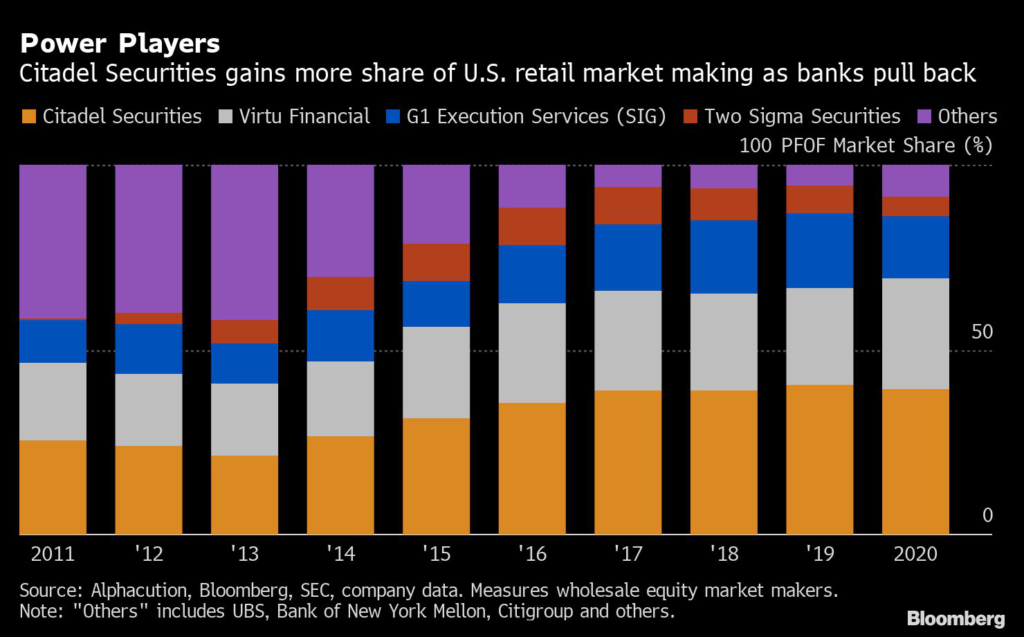

That has investment banks worried. After ceding retail market-making share to Citadel Securities, unable to compete on technology and hamstrung by rules from after the financial-crisis, they’re staring at a fresh threat to the business they typically handle from clients like hedge funds and pension investors. The firm is also unsettling Wall Street’s efforts to retain its best talent.

Citadel Securities poached top trader Etienne Lussiez from Citigroup Inc. in January. JPMorgan Chase & Co. Chief Executive Officer Jamie Dimon listed Citadel Securities among “tough competition” in June. Goldman Sachs Group Inc. executives identified the company as a bigger threat than its long-established European rivals at an internal trading division meeting last year. Griffin is said to revel in poaching employees from Goldman, having wanted to build a competitor to Wall Street banks, another person familiar with the matter said.

A spokesperson for Citadel Securities said it does not revel in hiring talent from Goldman Sachs or anywhere else and “attracts world-class talent from across finance, technology and academia.”

“They have won so profoundly,” said Paul Rowady, director of research for Alphacution Research Conservatory. “Banks and smaller rivals have not been able to compete at the cutting edge of technology and attracting talent — that train has already left the station.”

Expansion is bound to draw more scrutiny to the firm. Its market presence is so critical it could pose a threat to financial stability if its systems falter, some say.

Much of the meme-stock controversy centered around an often-attacked practice that allows retail brokers like Robinhood Markets Inc. to offer zero-commission trading. Under the payment-for-order-flow model, Citadel Securities and other market makers pay brokers to execute their retail orders, making them key to the rise of trading apps that fueled last year’s Reddit-inflamed short squeeze.

This market setup has drawn critics including Senator Elizabeth Warren, who said the company profits at the expense of customers during periods of extreme market turmoil — much like the swings set off recently by Russia’s recent invasion of Ukraine.

Gensler alluded to the possibility of banning PFOF, saying it puts investors at an information disadvantage and may not get them the best deal. Griffin has defended the practice, saying it helps democratize finance and that it’s actually a “cost” to the firm.

When put to some of the Citadel Securities executives in February, they zoom out from some of the controversy’s thornier issues. They speak of misconceptions about the firm and echo Griffin’s comments on the benefits PFOF affords small-time traders.

“All of a sudden we find our name on venues and getting mentioned in places we weren’t mentioned before — it’s something we weren’t planning for,” said Zhao, when pressed about the meme-stock craze. “We are focused on making the best decisions, regardless of whether our name is being mentioned or not.”

Retail investors get better prices and brokers get better economics because of how the market is set up, said Joe Mecane, head of execution services at the firm. Restricting PFOF could hurt investors and wouldn’t curb the order flow Citadel Securities receives, he said. “There is a big disconnect between what we do, what the message should be about what we do, and what the public perception ends up being,” he said.

At its offices on the 37th floor of the Citadel Center in downtown Chicago, display cases exhibit artifacts dating from long before the algorithmic trading era Citadel Securities helped drive: ticker tape from the Wall Street crash of 1929; a green jacket dating to the 1980s, when traders endured the boisterous pits of the Chicago Board of Trade. There’s an Xbox and a chess board. “The Devil in the White City,” about the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, shares a shelf with “Moneyball”.

From its original focus on equities and options, the company has expanded, including into interest-rate swaps and Treasuries, two businesses that were largely dominated by banks, COO Culek said.

On those trades, the firm has winnowed down the speed of liquidity — how long it takes to get trade prices back to clients — to a 10th of a second. It takes banks three to five seconds, Culek said. The firm said it executed approximately $26 billion of Treasuries volume per day in 2021. It also handled $11.4 billion in notional average daily volume across Treasuries and interest rate swaps for clients last year, a 150% jump from 2019. Executives say more is to come.

“There is still a very large percentage of the world’s asset classes that don’t trade electronically. Many banks provide liquidity in those products — over time more of those things are going to go electronic — and we are going to become a key liquidity provider,” said head of business development Jamil Nazarali. “Most of our growth is ahead of us.”

(Updates with Citadel Securities spokesperson comment in 16th paragraph, data on Treasuries in penultimate paragraph.)

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.