(Bloomberg) — Central banks across the globe are drawing lessons from 19th century history in their push for modern payment technologies, according to the chief of Sweden’s Riksbank, the world’s oldest central bank.

The use case for central bank-issued digital currencies (CBDC) — such as the digital yuan or the digital euro being studied in China and Europe — arises from a similar dilemma faced by monetary authorities in the late 1800s. Both then and now, central banks had to assert their footprint in money supply, Riksbank chief Stefan Ingves argued in a panel moderated by Bloomberg’s Stephanie Flanders on Tuesday.

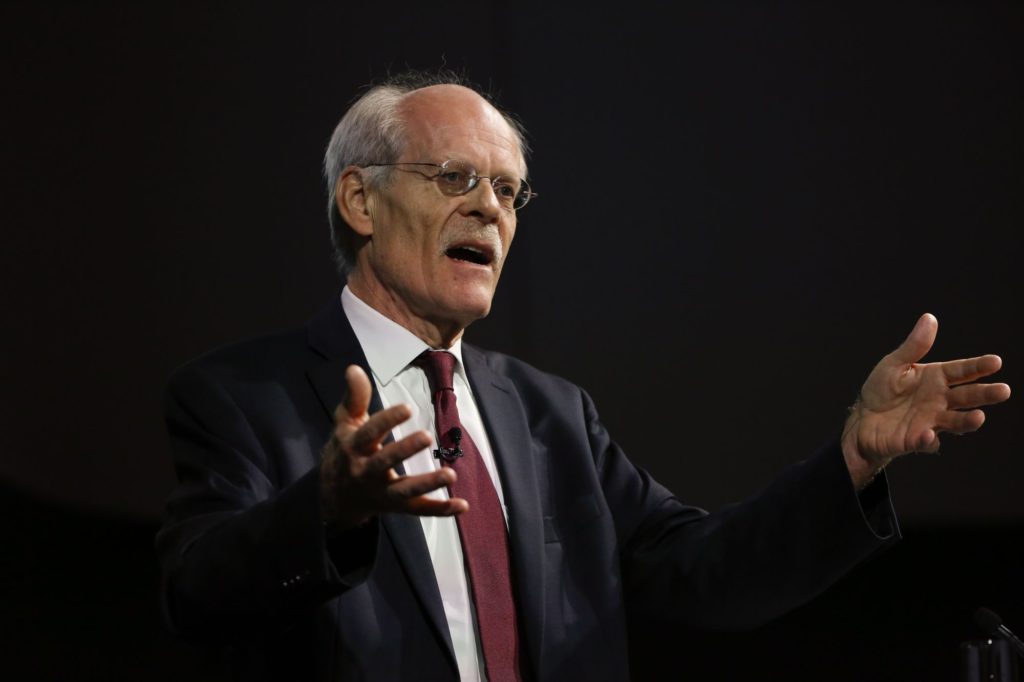

“About a hundred years ago, every sovereign state decided that the government should have a monopoly on the production of money. The reason was that only the government could provide a currency that trades at par with no questions asked” and isn’t subject to bank runs, said Gary Gorton, a professor at the Yale School of Management who spoke alongside Ingves.

“The question of whether states should have monopoly over money production has arisen again,” Gorton said.

In the past, it was common for consumers and businesses in many parts of the world to transact using numerous privately-issued banknotes and coins, frequently causing conversion and settlement headaches. Monopolizing currency issuance established a division of labor between central banks and commercial institutions that is common today, where the latter focus on lending.

Yet declining cash use and a flood of new payment technologies means the bulk of money transacted by consumers is actually no longer issued by central banks. Instead, electronic money on bank accounts marks a liability of commercial banks. The growing popularity of cryptoassets like Bitcoin or stablecoins may pose yet another challenge to central banks’ control of the means of payment.

“In the old days everything was on paper. Now we’re moving into another world where nothing will be on paper,” Ingves said. Central banks should not let go of the structure established more than a century ago, he argued, because “if history gives us any guidance, that’s a bad idea.”

“We need to ensure we can maintain the exchange rate between central bank money and private sector money,” he said. Otherwise “you end up with serious problems in the system, and those were exactly the problems that we had in the 1800s when banks issued all sorts of notes and coins on their own.”

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.