(Bloomberg) — When a retail union targeted an Amazon.com Inc. warehouse in Alabama last year, organizers generally avoided provocation, holding rallies far from the facility and urging placard-carrying activists to stay off the company’s property.

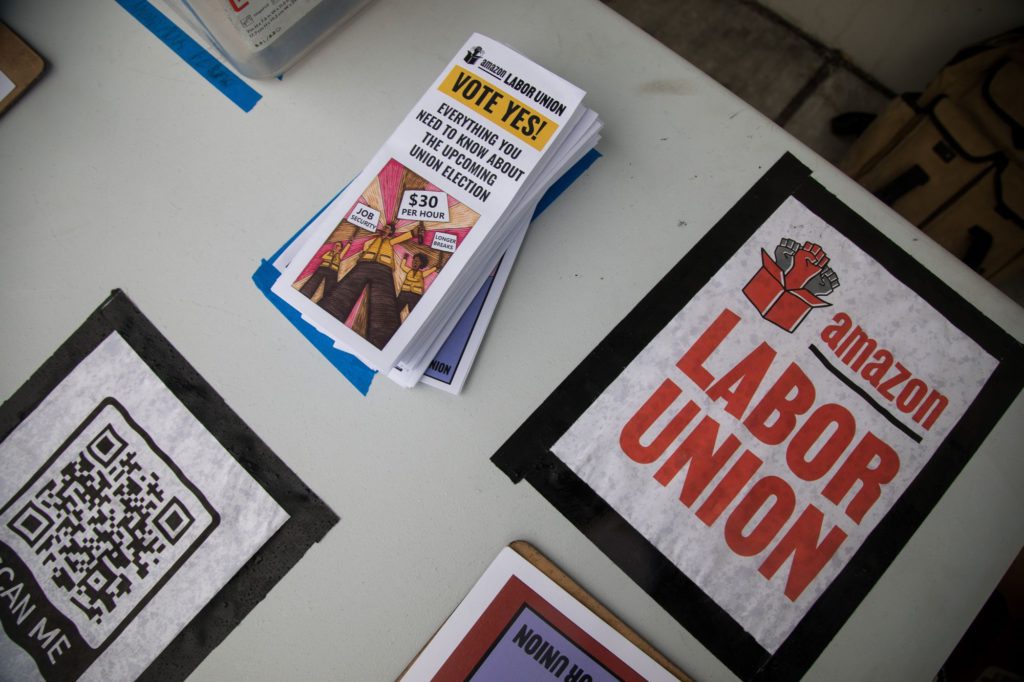

Christian Smalls, an upstart labor leader hoping to unionize Amazon facilities in Staten Island, New York, has tossed that playbook. Over the past couple of years, Smalls has tweeted photos of Amazon consultants he deemed “union busters” and encouraged supporters to disrupt anti-union meetings inside the gigantic JFK8 warehouse. Meanwhile, he staked out the Amazon parking lot, handing out union literature, playing loud rap music and buttonholing workers as they came and went.

Time and again, Amazon says, it warned Smalls he was trespassing. Finally, on the afternoon of Feb. 23, the company called the police, and Smalls was arrested and charged with trespassing, resisting arrest and obstructing governmental administration. (Smalls says a judge adjourned the case for six months and will dismiss the charges so long as he isn’t charged with a crime during that time.)

One can argue with his methods—and some do—but it’s hard to deny Smalls’ achievement. In mid-February and early March, his fledgling Amazon Labor Union won two important victories: approval from federal labor officials to hold a union election at one warehouse and sufficient worker support to hold a vote at a second facility nearby. The first election is scheduled to commence on Friday and run through March 30, while the second vote is set for April 25 through April 29. If successful, Smalls will have created not just the first union to breach Amazon’s U.S. warehouses, but perhaps cemented his position as the face of a new labor movement.

In Amazon, Smalls confronts a deep-pocketed foe that handily defeated the efforts to unionize the Alabama warehouse last year. The novice labor organizer has made rookie mistakes, including failing to gather enough employee signatures in his first attempt to force an election at the JFK8 warehouse. But he and his allies have come this far with little support from organized labor. “I know I’m a misfit, there’s no shame in my game,” Smalls says. “I say what I say and that’s what got me here. The same thing with the union: It represents what the workers want to say.”

In an emailed statement, Amazon spokeswoman Kelly Nantel said: “Our employees have the choice of whether or not to join a union. They always have. As a company, we don’t think unions are the best answer for our employees. Our focus remains on working directly with our team to continue making Amazon a great place to work.”

Smalls, 33, grew up in Hackensack, New Jersey, playing basketball, football and running track at Hackensack High School. He had a short stint as an independent rapper (one of his songs can be found on Amazon, though it can’t be played or purchased) but abandoned these aspirations after having kids, a twin boy and girl now aged nine. From 2012 to 2015, Smalls worked various jobs in New Jersey, including stints at Walmart, Home Depot, a grocery warehouse distributor and MetLife Stadium. He toiled at Amazon warehouses for a couple of years, then in 2018 went to work at the then-new JFK8 fulfillment center in Staten Island, where he supervised employees picking items.

When the pandemic struck in 2020, Smalls and thousands of his colleagues became so-called essential workers, who were expected to pick, pack and ship products to home-bound customers. It was a scary time because no one knew if Covid-19 was circulating in the warehouse, and Amazon was then providing little guidance. “It was business as usual,” Smalls told Bloomberg last year. “We weren’t socially distanced. We were sitting in the cafeteria shoulder to shoulder, you know, eating lunch.”

After workers began calling in sick and showing up with symptoms, Smalls and colleague Derrick Palmer organized a walkout. Not long after, Amazon told Smalls to stay home because he had possibly been in contact with an infected colleague. Smalls showed up for a rally and was fired, prompting him to file a lawsuit alleging racial bias in Amazon’s Covid safety protocols. (A judge dismissed the case in February.)

As tensions rose in Staten Island, senior Amazon executives discussed the situation on a call. In a leaked transcript of the meeting published by Vice, General Counsel David Zapolsky suggested focusing attention on Smalls, who is Black, because he “wasn’t smart or articulate.” Critics decried the comments as racist. Zapolsky later apologized and denied that his remarks were racially motivated.

The incident was a galvanizing moment for Smalls. “Ironically they said to make me the face of the whole unionizing efforts against Amazon,” he told Bloomberg last year. “And from that moment forward, that’s when I really started to really get involved in organizing. And now I’m trying to make them kind of eat those words.”

With Covid spreading across the U.S., Smalls started the Congress of Essential Workers, which mostly traveled around the country protesting Amazon and founder Jeff Bezos. Smalls and his associates weren’t above pulling stunts of questionable taste, once deploying a mock guillotine outside Bezos’ Washington mansion. These antics alienated some activists, who believed Smalls was just seeking attention. “You have to be more strategic,” says Adrienne Williams, a former Amazon delivery driver and member of the Congress of Essential Workers. “He wanted the publicity that came with that fake protesting.” Smalls denies that.

Williams and other members of the group also signed a public letter criticizing Smalls for failing to set up a non-profit and for using money raised on a personal GoFundMe page for his advocacy. Williams says she felt Smalls was blurring the lines between his activism and his own needs. An attorney for Smalls sent the signees a cease-and-desist letter after the missive spread online. “The money I raised, people donated to me personally,” Smalls says. “What I did with that money is what I did with it.”

Started in April 2021, the Amazon Labor Union targeted four facilities that, according to the company, employ about 10,000 workers. Attempting to sell the benefits of union membership to that many people is a daunting task; last year, according to the National Labor Relations Board, bargaining units comprised about 60 people on average.

Smalls argues that his union has a better shot at winning the election than more established players like the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union, which lost in Alabama and is currently contesting a do-over vote there that ends March 28. He notes that New York is a union town, unlike Bessemer. New York State has the second highest union membership in the country, with 22.2% of workers belonging to a union, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. But most of them work in the public sector.

Smalls has projected a fun-loving, we’re-just-like-you vibe to win over workers—dancing, joking around and snapping selfies while collecting signatures. He wanted to avoid what he views as mistakes made in Bessemer, where the union touted support from politicians and celebrities. “Amazon definitely attacked that aspect of it,” he says. “The campaign lost touch with their workers.” Celebrity sightings in New York have been rare: In mid-March activist-actor Susan Sarandon dropped by an ALU phone-canvassing event.

Read more: Teamsters Boss Has Tough Words for UPS and Sets Sights on Amazon

While organized labor can draw on union dues to help finance campaigns such as the one in Bessemer, Smalls says he has mostly relied on GoFundMe to fund the ALU’s activities—raising more than $100,000 since April 2021. Early on in the campaign, Smalls also accepted legal assistance and help collecting signatures from the local chapter of the United Food and Commercial Workers Union. Smalls says the union is still paying the fees for an ALU attorney. He doesn’t take a salary, and says he has relied on money raised on his GoFundMe page along with financial support from family and friends.

The Staten Island saga has made Smalls into something of a media darling and earned him qualified praise from RWDSU President Stuart Appelbaum, who said in an interview: “I’ll give him credit for taking advantage of the moment and the groundwork that was laid by the Bessemer campaign. I want him and everyone else organizing Amazon workers to be successful.” John Logan, the department chair of labor and employment studies at San Francisco State University, says the ALU’s independence prevented Amazon from defining itself as a job creator standing up to Big Labor. “I hate the word optics,” he says. “But the optics are kind of ‘Amazon the corporate bully trying to crush the little guy who’s on the side of the workers.’” Calling the police on Smalls, he adds, risked backfiring.

The ALU and Amazon have been competing aggressively to win hearts and minds on the warehouse floor. As in Alabama, the company holds “information sessions,” during which managers and labor consultants try to persuade workers that a union wouldn’t necessarily improve their wages and benefits. In early February, workers belonging to the ALU disrupted one of these meetings by challenging management’s talking points, stalling the presentation. In response, according to a video reviewed by Bloomberg, a manager at the JFK8 facility told workers not scheduled to attend that they could be dinged for “insubordination.” The meeting was canceled.

Gauging the strength of ALU support isn’t easy. Unions need only collect signatures from 30% of workers to force an election, meaning the rest of the workforce could be pro or anti-union. “A lot of people are on the fence,” says one worker, who plans to vote in favor of unionizing. “One girl said no because she said Chris doesn’t have the experience and she doesn’t need anyone being her voice. Me? I can’t speak up for myself.” The election in Bessemer was instructive. Despite months of campaigning and support from leading politicians including President Joe Biden, the union lost by a 2 to 1 margin and may lose the second election, as well.

Smalls has refrained from setting out a detailed agenda should the ALU win but says he has surveyed workers to assess their priorities. Among them: bringing back monthly productivity bonuses the company eliminated in 2018, giving hourly workers Amazon stock and raising pay to $30 an hour compared with the current average starting wage of $18 an hour. “If we lose, it’s not the end of the ALU, it’s really the beginning,” Smalls says. “We have a couple of chances here. We’re hoping that we’ll be successful the first time around.”

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.