(Bloomberg) — Sweden’s top army officer has been waiting a long time to get back to the windswept Baltic Sea island of Gotland.

Karl Engelbrektson was a unit commander on Gotland in 2005 when Sweden withdrew its military from the crucial perch in the center of the Baltic, taking advantage of the post-Cold War peace. Even then, he thought the move was ill-judged.

“Disbanding large parts of the armed forces, in the peace euphoria of that time, may have made sense to a lot of people,” Engelbrektson, clad in army fatigue next to a German-made Stridsvagn 122 tank, said in an interview at the Gotland base in late March. “History proves that this was a mistake.”

Gotland gives the Swedish military a dominant position in the Baltic from which it can control critical naval routes and airspace, a strategic bastion that seemed irrelevant before Russia invaded Ukraine. A wealthy Nordic nation that had become accustomed to being far away from war zones, Sweden — along with governments across the region — is preparing for the possibility, unthinkable until recently, of a conflict with Russia.

Sweden lies at the center of the Baltic Sea region, the northern flank of the European Union, where neighboring Finland shares a 1,300-kilometer (800-mile) border with Russia and the Baltic states — Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania — had a half-century history under Soviet rule.

When Sweden and Finland held military exercises off Gotland in March, four Russian fighter jets briefly violated Swedish airspace east of the island — an incident the Swedish Air Force regarded as especially serious given the context.

Vladimir Putin’s invasion order — and experts on Russian state television holding forth on an incursion into the Baltic — has triggered a rush across the north of the EU to top up defense budgets, arm previously hollowed out militaries and deliver weaponry to Ukraine. In Sweden and Finland, both of which carefully remained non-aligned during more than four decades of the Cold War, consensus is building to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

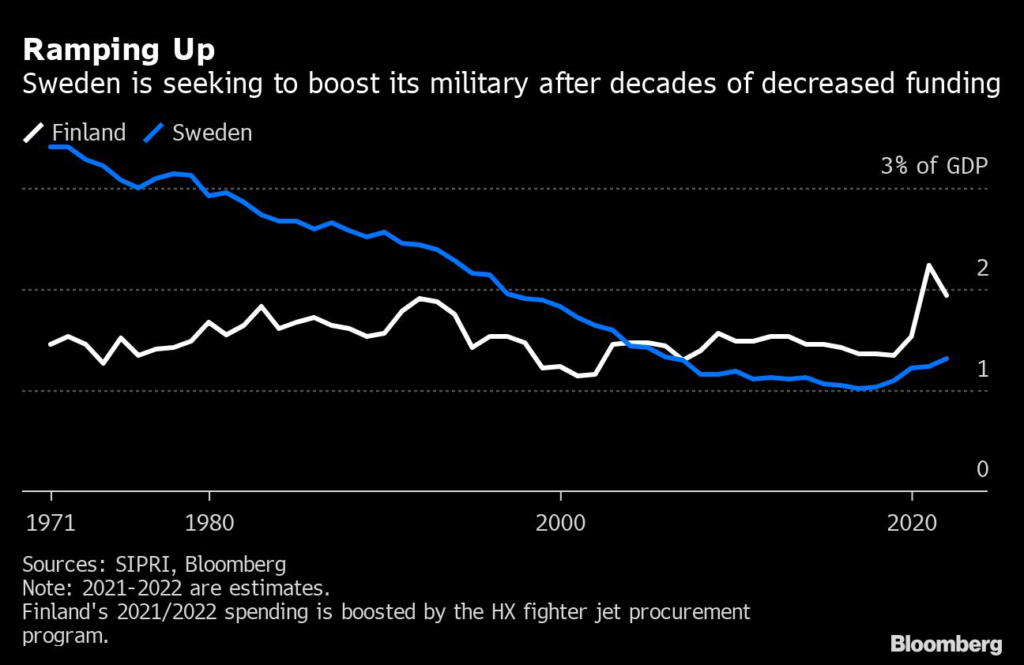

Few places encapsulate the shift as Gotland, where Sweden stationed artillery and anti-aircraft units as well as an armored brigade of several thousand troops in the decades when western Europe faced the Soviet threat. In the 1960s, the nation could muster 800,000 troops from a population of fewer than 8 million, and dished out 4% of its gross domestic product on defense.

After the collapse of the Berlin Wall, spending plunged and Sweden embraced the new security equilibrium. When Engelbrektson’s unit left in 2005, Putin was still making overtures to the U.S. and its allies and Gotlanders faced only the onslaught of summer tourists in search of crisp Baltic beaches and the medieval walls of Visby, the county seat.

Although a permanent garrison returned in the years after Putin seized the Crimean peninsula from Ukraine in 2014, the Swedish public was largely sanguine until recently.

Security experts have noted that the Swedish island would be a linchpin in any Russian incursion into the Baltic states. Lieutenant General Michael Claesson, the chief of the Swedish military’s joint operations, said control over Gotland gives a nation effective control over the Baltic.

Any NATO response to a rapid attack would be stymied if Russian forces held the island, Claesson said. The island, Sweden’s largest, got a shout-out in Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy’s address to the parliament in Stockholm, who said all of Russia’s neighbors are in danger.

“You can make it harder to defend NATO territory in the Baltics, as well as Sweden and Finland,” the officer said in an interview. “You also have to consider that we aren’t part of any military alliance, and it may be tempting to Russia to challenge a country that doesn’t have formal security guarantees.”

War jitters on Gotland have taken hold, even though Sweden hasn’t ceded control of the island since 1808, when it was briefly occupied by Russian troops during the Finnish War, in which the Russian Empire helped itself to a third of the Kingdom of Sweden — modern-day Finland.

“We get questions every day about shelters, about how much water and food you should store at home, et cetera,” Rikard von Zweigbergk, the head of preparedness and civil defense for the Gotland region, said in an interview.

Claesson gave the order to send reinforcements and armed personnel carriers to Gotland in January. The deliberate show of force prompted the Kremlin to blame Sweden for escalating tensions in the region. The complaint, from Putin’s chief spokesman, Dmitry Peskov, gave Claesson a “sense of accomplishment,” he said.

Sweden’s martial action cuts to the heart of a policy debate in the country, where officials are torn between caution over a delicate regional balance and a recent surge in public support for joining NATO.

Polls now show a plurality of Swedes favor entering the alliance. Prime Minister Magdalena Andersson — who faces an election in September — isn’t ruling out membership, even as she’s said an application in the current situation could threaten regional security. Her government, which currently spends about 1.3% of GDP on defense, wants to bolster that level to 2% of GDP — the NATO threshold — as soon as “practically possible.”

“The war in Europe will affect the Swedish people,” Andersson said earlier in March. “Russia is now threatening the entire European security order, on which Europe’s countries, including Sweden, base their security.”

Sweden, known more for its high living standard and lack of corruption, is no stranger to arms. A significant weapons exporter, it has provided everything from artillery rounds to jet fighters to militaries across the world. The anti-tank shoulder-fired weapon NLAW, originally developed by Sweden’s Saab AB, is one of the most important pieces of equipment for the Ukrainian forces fighting the Russian army.

Engelbrektson, the army chief, said on Gotland that the financial commitment and Sweden’s industrial capability put it in a good position.

“We are in the fortunate position that we can actually throw money at a problem and get results,” he said.

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.