(Bloomberg) — Red Star FC, a small football club with a tired, old stadium in a northern suburb of Paris, has rebellion in its DNA.

One of its most famous players was Rino Della Negra, a communist and resistance fighter executed under the Nazis in World War II. Red Star has a stand named after him, in which many hardcore fans cheer their team. It was from here where smoke bombs were hurled and banners unfurled this month in opposition to Red Star’s proposed takeover by Miami investment firm 777 Partners.

The protest, which saw a game against FC Sete 34 abandoned, was among the starkest indications yet of growing opposition across Europe to the multiclub ownership model that’s all the rage for a new wave of data-driven football investors.

Another came last week when Sheikh Mansour bin Zayed Al Nahyan’s City Football Group, the Abu Dhabi-financed company that owns English Premier League champions Manchester City FC and teams in the U.S. and Asia, saw an attempt to bring NAC Breda into its fold rejected by followers of the Dutch side.

“I feel that we have retrieved what they almost took away,” said Arjan van Toor, founder of the NAC Breda supporter group B-Side Rats.

“We feared that CFG would send a lot of talent from all over the world here, while not focusing on the youth from Breda,” he said. “We were afraid that we were going to lose the club’s identity.”

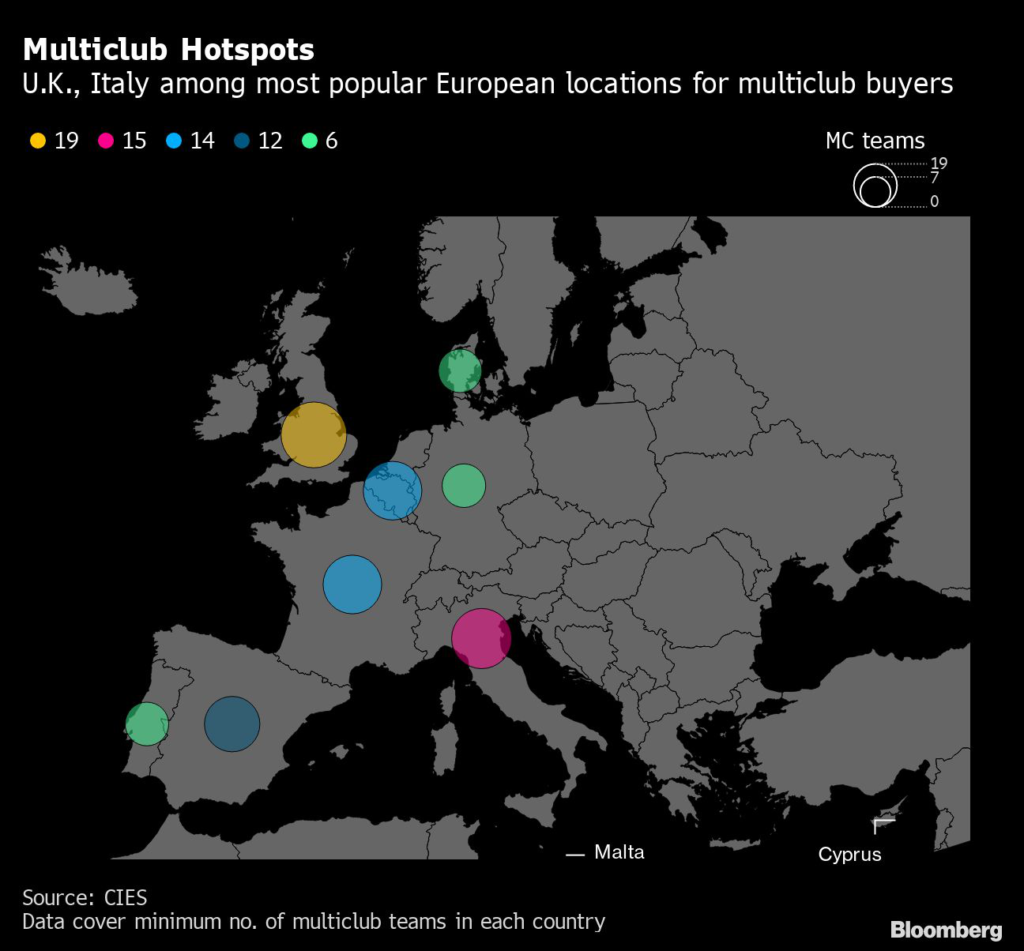

At least 24 football investments were made by a multiclub owner in 2021, according to data compiled by research group CIES — a record. This year is already on course to top that thanks to a string of deals across Europe and Latin America.

U.S. investors, in particular, are drawn by the growth potential and lower valuations in European football compared with sports franchises back home. Such is their appetite for a slice of the world’s favorite sport that some have even started targeting clubs in Germany, where strict ownership rules prioritizing fan needs over financial excess have for years deterred buyers.

777 and its co-founder Josh Wander have been trying to add Red Star to their stable of historically significant clubs, which already includes Italy’s Genoa, Standard Liege in Belgium and a stake in Sevilla FC of Spain. Red Star announced on April 6 that it was in exclusive negotiations to sell itself to 777.

But in the city where foreign money bankrolls the mighty Paris Saint-Germain FC, 777’s promises of new investment and a raised global profile for third-tier Red Star are falling on deaf ears among its largely anti-capitalist fanbase.

“The Red Star is our club, our world,” a fan group named after Della Negra wrote in an open letter to 777 that was posted on Twitter this month. “In our world, there is no place for a conglomerate of football clubs, for trading of players between subsidiaries or outrageous marketing.”

For the time being, Red Star fans won’t be able to make these feelings known from the Rino Della Negra stand. The club has been ordered to play its matches behind closed doors after this month’s fiery protests.

Representatives for 777, City Football Group and Red Star declined to comment. Red Star’s owner Patrice Haddad said in a statement earlier this month that he picked 777 due to their determination, understanding of the club’s uniqueness and their willingness to commit sizeable financial resources.

Fan Disfavor

Multiclub proponents point to its advantages as a system for developing future stars of the game without the need for hefty transfer fees. Cost synergies spanning everything from human resources to scouting, and the potential to strike more lucrative sponsorship deals, have also fueled interest in the structure.

“From an owners’ perspective, the multiclub model derisks the investment,” said Kieran Maguire, a lecturer in football finance at the University of Liverpool. “It allows for continuity and consistency across the whole group in terms of training techniques and players’ development.”

That doesn’t wash with critics, who say this kind of ownership stifles competition and creates farm teams with the sole purpose of serving the trophy asset within a group at the cost of their own standing and success. In a written response to a UEFA consultation on the future of European football, fan body SD Europe in September described the model as a “growing threat” to competitiveness in the game.

“These groups are creating a system of feeder clubs that serve as training grounds for higher-level endeavors,” SD Europe wrote. “For fans of the feeder clubs, the chance or the dream of winning anything would be diminished.”

Pacific Media Group, one of football’s biggest multiclub exponents, is another that’s feeling the heat. Two of its clubs, AS Nancy-Lorraine of France and Barnsley FC in the U.K., were relegated from their respective leagues on the same day last week after seasons in which supporters of both have publicly voiced opposition to their owner. Nancy’s game against Quevilly-Rouen was abandoned on Friday after fresh protests.

Paul Conway, Pacific Media Group’s co-founder, said that, for many football fans, it’s not so much the multiclub model as foreign investment in general that’s the problem. “It’s just an anti-investor thing,” he said.

Talent Pools

The U.K., France and Belgium are among the richest European hunting grounds for investors seeking to acquire teams, in no small part because of their reputations for producing exceptional, young talent. This can afford owners of clubs in multiple jurisdictions the chance to move the brightest stars in their stables to where they’re needed most, before eventually selling them on for big money.

When Pacific Media Group’s Danish team Esbjerg fB was short of players last summer, Barnsley loaned the club emergency backup. The move meant Esbjerg got the players it needed and one of them, Matty Wolfe, developed to the point where he was able to return to Barnsley as a first-team regular.

“One of the benefits of the multiclub model is that when a club has a down year, other clubs within the system can help it in rebuilding for the following season,” Conway said.

Not all are opposed to multiclub owners. Fans of Botafogo took to the streets in wild celebration in January at news the Brazilian team would be bought by John Textor, another U.S. investor whose portfolio includes English Premier League team Crystal Palace FC and Belgium’s RWD Molenbeek.

Crystal Palace is backed by others including David Blitzer, the Blackstone Inc. executive who’s also invested in German team FC Augsburg. Under multiclub ownership, the south London team has carved out an exciting brand of attacking football that’s impressed both fans and pundits.

“If you start with the belief that the benefits are going to flow freely and in all directions, then you can have something amazing,” said Textor of the multiclub model. “If you start with a bias about one club being stronger than the others, then you have a problem from the beginning.”

Capitalist Football

Back in Paris, 777 is on a charm offensive to ensure it succeeds with its takeover of Red Star. In mid-April, Wander and other representatives from the firm met with Saint-Ouen mayor, Karim Bouamrane, to talk through their plans as owners ahead of a public discussion on the deal before the summer.

To be sure, Wander may find it harder to convince followers of the club that they can enjoy the benefits of private equity money while at the same time staying true to their grassroots values. Many are in no mood for a sit down and “do not want to see capitalist football,” according to Jules Neyret, a member of Red Star supporter group Collectif RS Bauer.

“We want a club that respects its area also and that’s impossible to do if it owns four or five clubs,” Neyret said. “If the main thing you’re interested in is sporting success, then you should go to support PSG.”

(Updates with Red Star comment in 13th paragraph)

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.