(Bloomberg) — More people may be once again hailing a ride from Uber Technologies Inc. and Lyft Inc., but investors remain wary that efforts to woo back more drivers could derail profitability goals.

Lyft plunged as much as 35%, the most ever, dragging Uber down more than 12% after both companies reported quarterly results that pointed to strong demand for rides, but failed to reassure Wall Street that a driver shortage that’s cost the companies hundreds of millions of dollars in bonuses was abating.

“We want to make sure Uber and Lyft don’t have to keep incentivizing drivers every time there’s a shock to the system,” said Robert Mollins, an analyst at Gordon Haskett Research Advisors

The driver shortage underscores the challenge of grappling with pandemic-induced swings in demand and reveals the fragility of a labor model ill-equipped to address them. By hiring drivers as independent contractors, ride-hailing companies were historically able to offer lower prices than traditional taxis. But the pandemic destabilized this workforce after demand for rides cratered and many found other jobs, were better off collecting unemployment benefits, or were more concerned about the risk of infection from being in close quarters with passengers.

While riders have flocked back as they resume office commutes and trips to the airport, luring back drivers and onboarding new ones is taking more time and money than investors expected. A spike in gas prices when the war in Ukraine broke out has dealt a blow to recruitment efforts, just as companies were scaling back bonuses. Both Uber and Lyft have added fuel surcharges to rides in a bid to help ease drivers’ gas bills.

Read more about Lyft’s earnings results that sent shares plunging the most ever

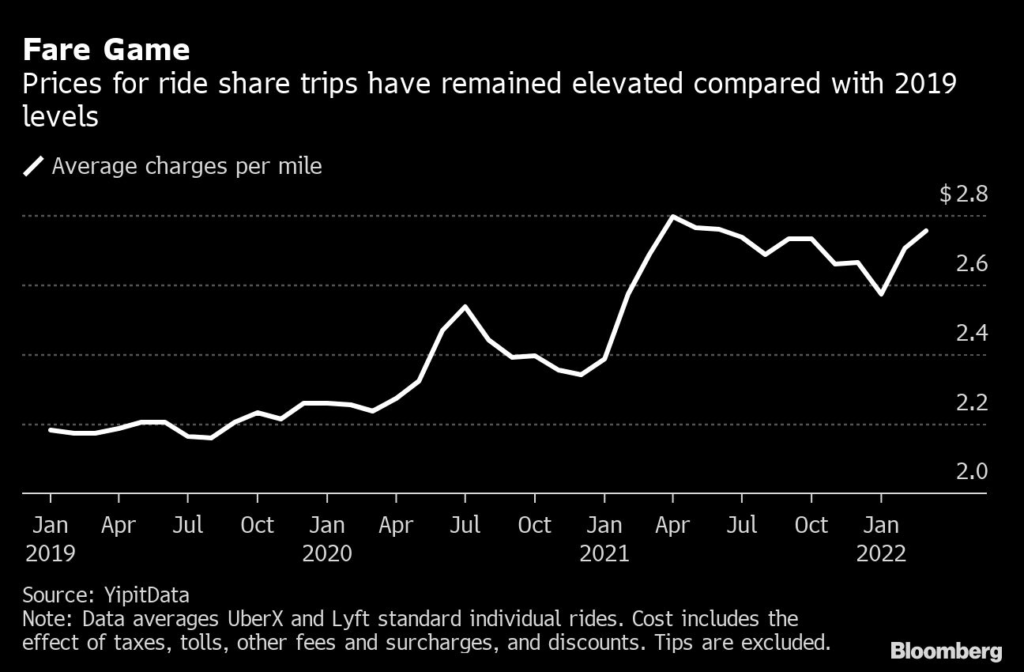

Solving the riddle of balancing riders with drivers is key to ensure the apps are still cheap enough and fast enough to not turn customers away. The average rideshare trip in the U.S. cost about $20 in the first quarter, up some 45% compared with the same period in 2019, according to market research firm YipitData. Meanwhile, average wait times during the week ending April 29 were roughly six and a half minutes, reverting back to December levels when shortages were more pronounced, a Gordon Haskett analysis analysis of 30 cities showed.

Once considered among the flagship Silicon Valley startups, disrupting the transportation model as we knew it and ushering in a new era of mobility, Uber and Lyft have seen their favor fade as they’ve had to reckon with city regulations and a pandemic that forced people into lockdowns. Lyft is down more than 70% from its 2019 initial public offering price of $72. Uber is off almost 40%.

The two companies laid out divergent strategies for their plans to boost drivers and meet an expected surge in ridership as Covid-19 wanes.

Lyft said it would ramp up spending on incentives in the second quarter and said it expects the imbalance of supply and demand to dissipate when the pandemic fully subsides. Meanwhile, Uber touted the benefits of its multi-vertical business, which includes food-delivery unit, Uber Eats. The delivery service has served as a unique pipeline for drivers for Uber to tap after many shifted to ferrying meals when rideshare demand tanked and now it gives them the unique opportunity to make money on both services.

Uber also said it has been making tweaks to the driver app, like unlocking the ability to see upfront fares before accepting a ride, improving maps and removing bugs. Rather than increase incentives, Uber plans to instead focus on its “holistic product experience as a way to attract, engage and retain earners,” Chief Executive Officer Dara Khosrowshahi said.

Still, Uber may not be able to fully escape incentives and analysts were concerned about a potential subsidy-war.

“If Lyft gets really aggressive with incentives, Uber might have to respond,” D.A. Davidson analyst Tom White said, noting this could have knock-on effects on profit margins.

The threat of eroding profits in the course of spending more on driver incentives looms large over Lyft and Uber, which reached profitability for the first time as public companies last year, though Uber seems to be seeing stronger demand, helping it pull ahead of its smaller rival. Lyft gave a forecast for earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization of $10 million to $20 million in the current quarter, substantially missing the $81 million Wall Street projected. Uber said it sees adjusted Ebitda of $240 million to $270 million, with the top end of that range beating the average analyst’s estimate.

Read more about how Uber managed to sidestep Lyft’s earnings debacle

Lyft’s disappointing outlook underscores the San Francisco-based company’s struggle to claw its way out of the pandemic.

Its forecast for adjusted Ebitda in the current quarter would be the second sequential quarterly decline. Chief Financial Officer Elaine Paul said the company feels like the worst is behind it, after omicron, and this coming quarter is “an opportunity to invest in kick-starting the next year of growth. We will do so with a focus on drivers, the overall marketplace and some additional brand marketing.” She said some of the costs related to driver incentives would be passed on to consumers through higher prices but others will weigh on profitability.

Though Lyft recorded a 40% increase in the number of drivers in the first quarter from the previous year, the company plans to invest more to boost driver supply in the second quarter, Paul said.

Meanwhile, Uber’s Khosrowshahi said the company’s first-quarter results “make clear that we are emerging on a strong path out of the pandemic.” Khosrowshahi said Uber’s driver base is at a “post-pandemic high” and that it expects engagement to continue “without significant incremental incentive investments.”

Unlike Lyft, Uber was able to rely on its food-delivery business Uber Eats, which boomed during the pandemic just as ride share demand plunged. The delivery segment, which includes orders across restaurant, grocery and alcohol, has continued to grow despite indoor dining resuming, with bookings up 12% from a year ago to an all-time high of $13.9 billion.

Growth at Uber Eats has also helped funnel more drivers into its ride-hailing business. The ability to toggle between ferrying meals and people to make money has enticed drivers, many of whom shifted to food-delivery during the pandemic. “The success there has been very very significant,” Khosrowshahi said.

(Updates to add information about fuel surchage and historcial stock information.)

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.