(Bloomberg) — California’s carbon market was supposed to be a model for the US, harnessing the power of capitalism to fight climate change in the world’s fifth-biggest economy.

But nearly 10 years after “cap and trade” began, there’s little proof the system has had much direct impact on curbing planet-warming pollutants. California has seen big cuts in greenhouse gas emissions — but such gains have little to do with the much-vaunted carbon market. As officials debate how to reach the state’s goal of zeroing out emissions by 2045, critics on both sides of the political spectrum say the market isn’t working.

“The California cap-and-trade program is really a failed experiment in regulation,” said Jim Walsh, policy director for the Food & Water Watch environmental group, which says the system lets polluters pay to keep polluting. “It’s done little if anything to address the climate crisis.”

The issues with California’s carbon-curbing initiative in some ways echo those of Europe, whose own market languished for years before reforms gave it greater strength. The US example may offer lessons to China, which just started its own program after years of study.

California’s cap-and-trade system sets an annual limit—the cap—on the amount of emissions the state’s economy can produce. The cap gets tighter every year, lowering emissions. Companies buy an “allowance” for each ton they emit, purchasing these permits through quarterly state auctions or from a secondary market. Allowances in that marketplace are trading at $30.73, up about 50% in the last year.

Two big issues, many critics contend, undermine the system. The cap on emissions has never been tough enough to force much change on its own, even with efforts to tighten it. Oil refiners and other companies have spent more than $19 billion over the years on auctioned permits to emit greenhouse gases. The expense gets baked into the price of their products, boosting gasoline prices an estimated 24 cents per gallon, according to Argus Media, in a state with the nation’s priciest fuel. But those costs haven’t done much to lower emissions.

“We’re paying, but we’re not getting the results we wanted,” said state Senator Brian Dahle, whom the state Republican Party has endorsed for governor this year. He wants the program audited as the state grapples with an affordability crisis that may be pushing some residents to leave. “It’s driving up the cost of all goods in California, and if you’re on a fixed income or hourly wage, you’re feeling the pain right now,” Dahle said.

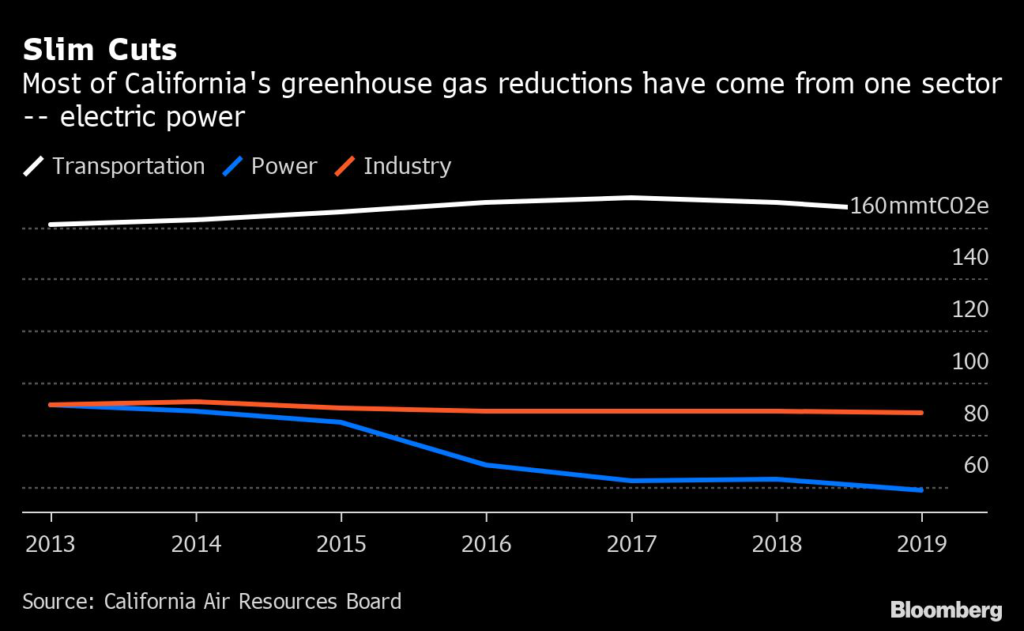

At the same time, other California climate programs that take a more direct approach — ordering specific industries to change their ways — have had a measurable impact on emissions. That’s particularly true in the electricity industry, whose rapid shift to renewable power has produced the state’s biggest emission cuts.

The result is that a program once considered a centerpiece of California’s climate fight is underperforming.

California officials released a report Tuesday with four proposals for eliminating net emissions by either 2045 or 2035, with the earlier date floated by Governor Gavin Newsom and favored by environmentalists. The proposals don’t specify which programs will be required to meet either deadline, but the report notes that cap-and-trade will probably cut emissions less in this decade than previously expected.

“It certainly is not up to par for being a driver of deep decarbonization,” said Chris Busch, research director at consulting firm Energy Innovation.

California’s emissions have fallen 6.5% since 2013, when the state started requiring companies to pay to pump greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Yet the big declines aren’t from cap and trade. California’s electric utilities, for example, slashed their emissions 36% from 2013 through 2019 due to a state law that forces them to use more renewable power, shifting from fossil fuels on a timeline set by the legislature. The first version of that law passed a decade before the carbon market opened.

Cars, trucks and other transport represent the state’s single biggest source of greenhouse gases, and since 2015 the cap-and-trade system has covered the fuel they burn. Transportation emissions in 2019, before Covid-19 hobbled the economy, were virtually identical to 2015, after rising for two years and falling for two. Officials credit the progress on stricter fuel-efficiency standards, electric vehicle incentives and more biofuel use—all due to state programs other than cap and trade.

European Example

The European Union launched a similar market in 2005, and the emissions it covers have since dropped by about a third. It didn’t always go smoothly. The global financial crisis in 2008 produced a glut of permits and tanked prices, which plunged from a pre-crisis high of 31 euros to 2.50 euros. A set of fixes to introduce automatic permit supply control, limiting any potential glut, restored credibility. Permits now trade above 80 euros.

China, meanwhile, started its national carbon trading scheme last year. It is the largest market for emissions, covering about 4.5 billion tons from the country’s power sector, and there are plans to expand to other industries including metals and airlines in the coming years.

Like Europe, California’s system has faced oversupply. Many companies covered by the system get some allowances for free in an effort to limit the impact to consumers. In February, an advisory committee report warned that companies have bought and held on to so many allowances—“banking” them for future use—that the state is in danger of missing its 2030 target of cutting emissions 40% below 1990’s level. The number of banked allowances, the report said, is larger than the emissions cuts expected from the program through that year.

The California Air Resources Board, which oversees the program, says banked allowances should be used up well before 2030.

The agency has tweaked cap and trade before and plans to revisit the program again next year. The cap has already been tightened—it now shrinks 4% per year compared to roughly 2% before 2021. Board Chair Liane Randolph said in an interview that she wants to see how those changes play out before considering more.

“We have a huge suite of strategies, and I don’t think we can leave any of those strategies on the table,” she said.

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.