(Bloomberg) — China’s tightening Covid rules and extended lockdowns are making a 2020-style V-shaped economic recovery a dim possibility this time around.

The slump in output may not be as deep as two years ago, when most of the country was under some form of restriction from late January through much of February following the outbreak in Wuhan.

Currently, areas making up only about 30% of gross domestic product are under full or partial lockdown, according to estimates from Nomura Holdings Inc.

However, this time around, given the ability of the highly infectious omicron variant to evade stringent controls, there’s greater risk of cities shutting down and then reopening repeatedly over several months.

Major hub Shanghai is still in lockdown after five weeks, and while cases are easing there now, Beijing and other cities are tightening restrictions to curb their own outbreaks.

The result is that businesses will have to live with the ever-present threat of disruption of the kind that’s halted production at companies like Tesla Inc.

and roiled supplies at Sony Group Corp. Consumer confidence and spending will likely also remain weak, putting the government’s GDP growth target of about 5.5% for this year further out of reach.

“The main concern is that given the high transmissibility of omicron, the containment and lockdowns could be in place longer than in 2020,” said Wei Yao, head of research for Asia Pacific and chief economist at Societe Generale SA.

“The confidence shock could be more sizable because the difficulties of extinguishing outbreaks make it almost impossible for business and households to forecast an end to recurring disruptions.”

CHINA INSIGHT: Plunging Subway Use, Home Sales Show Lockdown Hit

Unlike 2020, the economy must also weather the Covid crisis without one of its key growth drivers: property.

Home sales are dropping, real-estate investment is plunging and property developers are under severe financial strain after Beijing tightened rules last year to curb runaway prices and control debt.

Another difference from two years ago is the global environment.

Central banks around the world are hiking interest rates to curb soaring inflation, energy prices are spiking because of Russia’s war with Ukraine, and global demand for China’s exports — a key driver of the economy’s 2020 rebound — is set to slow.

“There is less space for policy easing than in 2020,” said Louis Kuijs, Asia-Pacific chief economist at S&P Global Ratings.

“Debt and leverage is materially higher now than at the beginning of 2020, constraining the ability to use fiscal policy and credit to support growth. On the monetary side, rising US interest rates also make it harder to ease monetary policy.”

Here’s a deeper look at how the economic impact of the current lockdowns differ from two years ago and what the implications are likely to be.

Retail Sales

Retail sales have never recovered from the pandemic, with growth rates well below the 8% or more expansion seen in 2019 and before.

Sales fell in March nationwide even before Shanghai was fully in lockdown, and with restrictions expanding nationwide since then, it’s expected that consumption dropped in April too.

In Shanghai alone, sales plunged 19% in March and consumption at restaurants and hotels was down almost 40% from a year earlier.

Mobility Data

The number of people riding the subway in 11 of China’s largest metro systems has slumped back to the level seen in 2020, as the lockdown of Shanghai and Zhengzhou and outbreaks in other cities forced people to stay home.

An average of 29 million people took the subway each day over the past week in those 11 cities, down 43% from a year earlier.

Even without Shanghai, that was still a 14% slump in the number of passengers, and outbreaks in other areas are continuing to affect ridership. Beijing has shut more than 70 metro stations so far to prevent infections from spiraling out of control.

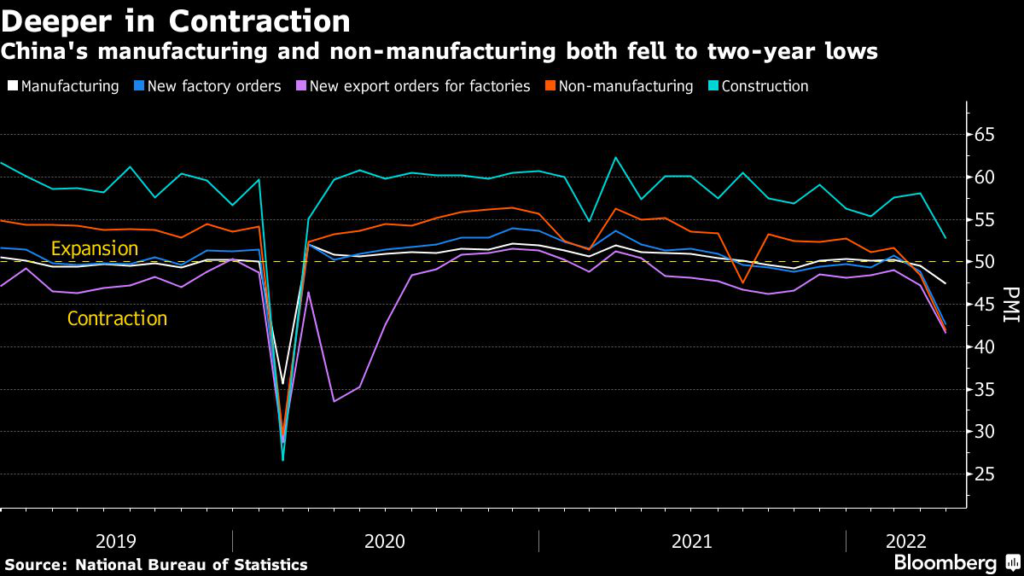

Manufacturing Slump

The official purchasing managers’ index for manufacturing, a leading indicator for factory output, fell to 47.4 in April, when Shanghai was in lockdown.

In February 2020, the index fell to 35.7, indicating a deeper contraction in output then.

To minimize production losses, local governments have allowed some businesses to continue operating in so-called closed looped systems, where employees are kept at factory locations and undergo regular Covid testing to prevent outbreaks.

“Productions are not completely shut and ports are still partially functional even in cities under lockdown such as Shanghai and Shenzhen with ‘close-loop’ management,” said Liu Peiqian, a China economist at NatWest Group Plc.

“Exports were also growing, albeit at very low rate compared to regional peers.”

However, while the government is trying to get production back on track, many foreign businesses say they’re still unable to resume operations.

Restrictions on the movement of people and testing requirements at border checkpoints have led to truck shortages, making it difficult for companies to transport their goods across provinces or to the ports.

Logistics Nightmare

The PMIs show disruptions to supply chains are almost as severe as in 2020. Suppliers are experiencing the longest delays in over two years in delivering raw materials to their factory customers.

Satellite data also show port activity is below levels seen in early 2020.

Disruptions to factory output and logistics resulted in an abrupt slowdown in export growth and added to strains on global supply chains.

Export growth slowed in April to its weakest pace since June 2020, while imports contracted for a second month.

Two years ago, exports contracted the most on record when the coronavirus outbreak led to extended holidays, depressed factory output, and blocked transport and movement across the country.

Property Woes

Even though many cities have loosened home purchase restrictions and cut mortgage rates this year, housing sales have continued to tumble, curbing demand in related industries from steel and cement, to furniture.

More importantly, the downturn has cut local governments’ income from land sales which is a key source of revenue, limiting their ability to boost spending to spur growth.

Many provinces are forecasting double-digit declines in land sale revenue this year, including rich areas like Beijing, Shanghai and Zhejiang. In 2020, regional authorities reported a 15.9% jump in the income.

An extra burden on local finances is the increased expenditure on virus testing.

Since the Labor Day holidays in May, many cities have implemented mandatory regular nucleic acid testing for residents to access public transportation and venues. If this strategy was expanded to the whole of mainland China, it would cost between 0.9% and 2.3% of the country’s GDP, according to an estimate from Nomura.

Job Losses

The surveyed unemployment rate climbed to 5.8% in March amid the lockdowns, the highest since May 2020, according to the latest official data.

In 2020, the jobless rate reached a peak of 6.2%.

The latest PMI surveys indicate a slightly smaller loss of jobs now than two years ago, but even so, employment in the manufacturing and non-manufacturing sectors in April were both at their worst levels since February 2020.

Going into this year, job losses were already mounting, especially among technology firms and after-school tutoring companies, after Beijing’s regulatory crackdown on those sectors.

Tech giants like Tencent Holdings and JD.com Inc. have made national news headlines with tens of thousands of layoffs.

Chinese Premier Li Keqiang held a national teleconference this month, warning of a “complicated and grave” job situation, language that conveyed more concern about the employment outlook now versus two years ago.

At the same meeting, Li’s deputy Hu Chunhua urged officials to “closely follow changes in the job situation, identify emerging problems in a timely manner and effectively prevent and resolve risks and hidden dangers in labor relationship and other issues,” a call that wasn’t made in 2020.

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.