(Bloomberg) — Elon Musk wants to mine it, China is scouring Tibet for it, battery makers are crying out for it. Lithium, the wonder metal at the heart of the global shift to electric cars, is in a full-blown crisis. Demand has outstripped supply, pushing prices up almost 500% in a year and hindering the world’s most successful effort yet to halt global warming.

The shortage of lithium is so acute that in China, which makes about 80% of the world’s lithium-ion batteries, the government corralled suppliers and manufacturers to demand “a rational return” to lower prices. Analysts at Macquarie Group Ltd. warned of a “a perpetual deficit,” while Citigroup Inc. nearly doubled its price forecast for 2022, saying an “extreme” rally could be coming.

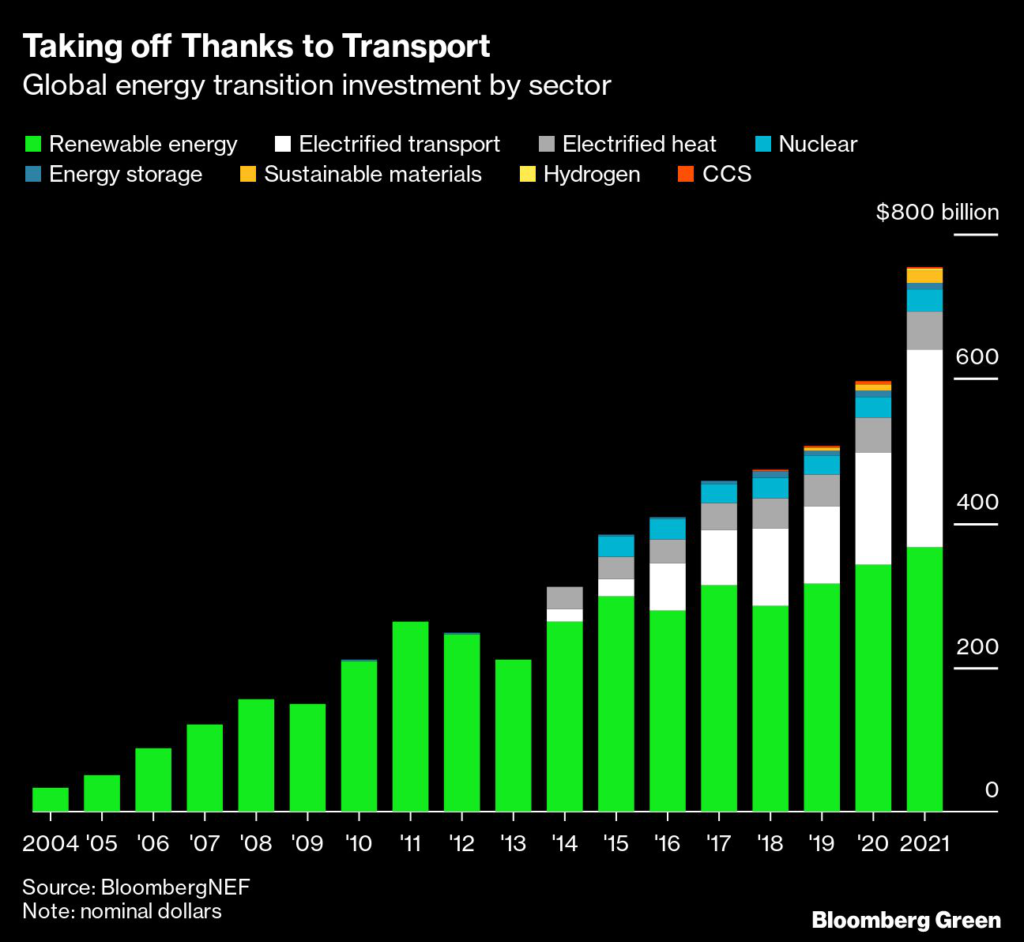

The consequences of failure to produce enough lithium are potentially devastating. Global investment in EVs has grown faster than any other new-energy sector over the past few years, outstripping even wind and solar power. Current lithium spot prices could add up to $1,000 to the cost of a new vehicle, Benchmark Mineral Intelligence said. Along with higher prices of other raw materials, that is reversing years of falling prices as EVs race to become cost-competitive with gasoline-powered cars. If battery makers can’t get enough lithium, it would curb the expansion of clean-energy vehicles, making it harder to meet global emissions targets.

“It looks like the expansion ramp up is not going to be fast enough to hit demand” over the next three years, said Cameron Perks, an analyst at Benchmark. EV makers “have been asleep at the wheel.”

The crunch prompted a characteristically blunt tweet from Musk in April. “Price of lithium has gone to insane levels!” he posted on Twitter. “Tesla might actually have to get into the mining & refining directly at scale, unless costs improve.”

Musk’s Tesla Inc. and Chinese automakers BYD Co., Xpeng Inc. and Li Auto Inc. have all already raised sticker prices, as has Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. Ltd., the world’s biggest EV battery maker. “The industry is facing very strong headwinds in terms of cost escalation,” XPeng President Brian Gu told Bloomberg TV in late March.

The silvery-white metal, the third-lightest element after hydrogen and helium, is in the throes of an unprecedented boom because a slump in 2018-2020 that halved its value caused chronic underinvestment in new sources of supply just as EV demand was taking off. For battery makers, those woes have been compounded by the pandemic and Russia’s war in Ukraine, which have snarled supplies of other ingredients they need, including nickel, graphite and cobalt.

Tightening supply and higher prices have prompted a flurry of acquisitions and joint ventures as battery makers and automakers try to secure supplies, and unleashed a wave of resource nationalism among governments. As early as last June, Fitch Solutions said lithium had become a “strategic mineral,” and warned of “rising government intervention.”

EVs and batteries drew $271 billion and $7.9 billion of investment respectively in 2021, according to Kwasi Ampofo, head of metals and mining at BloombergNEF. “The upstream part of the value chain has, on the other hand, attracted relatively low investment over the last five years,” he said.

Read: How Hot Is Lithium? A Chinese Mine Auction Draws 3,448 BidsLithium has taken a long time to hit the mainstream. Discovered in 1817 by Swedish chemist Johan August Arfwedson, it wasn’t produced in quantity until the US government began stockpiling it to make hydrogen bombs in the late 1950s. After the Cold War, production declined until the metal began to be adopted for use in light alloys, coin cells and then mobile phone batteries in the 1990s.

More than half of the global resources are located in the so-called lithium triangle between Argentina, Bolivia and Chile, where producers pump lithium-rich brine from underground lakes and allow the liquid to evaporate for 12-28 months to yield a slurry that can be profitably processed. Current technology recovers only about 50% of the lithium in the brine.

Much of the remaining supply comes from deposits of an igneous rock called spodumene, with Australia the biggest miner. The ore is roasted and leached with sulfuric acid and the silvery-gray residue typically shipped to China to be made into lithium hydroxide and lithium carbonate – compounds that can be combined with nickel or cobalt to make battery electrodes, or with solvents to make electrolytes.

The quickest way to increase supply is to ramp up output from these existing sources. Ganfeng Lithium Co., one of the world’s largest producers, said it’ll use record profits to boost output. Australia’s Pilbara Minerals Ltd. aims to raise production capacity more than 50% by the September quarter by expanding its Pilgangoora mine in Western Australia, a project that includes Chinese partners Great Wall Motor Co. and CATL.

For many brine-lithium producers, increasing output quickly is constrained by their permits and the time taken to let the liquid evaporate.

One longer-term solution is to find new deposits.

Mining superpowers Australia and Canada has both promised to help develop critical mineral resources, including lithium. China recently announced that its geologists had discovered a spodumene deposit on the Qinghai-Tibet plateau in the region of Mount Everest that could hold more than 1 million tons of lithium oxide. But it takes years to develop a new mine and, in some countries, the process is becoming more difficult due to resistance from local communities.

“There is plenty of lithium in the ground, but timely investment is the issue,” said Joe Lowry, founder of advisory firm Global Lithium. “Tesla can build a gigafactory in about two years, cathode plants can be built in less time, but it can take up to 10 years to build a greenfield lithium brine project.”

Read: Hunt for Lithium Sparks Rush Into Argentine Mountains

Rio Tinto Group’s proposed $2.4 billion Jadar mine on farmland in western Serbia, which would be Europe’s biggest, stalled as thousands of protesters marched in the streets. Rio says the mine, originally scheduled to open in 2026, would create more than 2,000 jobs and meet the highest environmental standards, including using recycled water and electric trucks. Savannah Resources’ Barroso project in Portugal and Lithium Americas Corp.’s proposed mine in Nevada are others that have to negotiate local opposition.

Chile’s Constitutional Convention this month approved an expansion of environmental governance that includes reshaping water rules and other environmental protections that could affect lithium producers if the charter is ratified in a September referendum. “If you’re a multinational company going in to Chile right now, you have to think twice, because you don’t know what the rules are,” Lowry said.

But lithium producers face an even bigger problem. Part of the reason consumers are prepared to pay a premium for an electric vehicle is that it’s better for the environment. But the lithium supply chain is far from green.

“Lithium mineral producers have the greatest need to reduce their emissions profiles,” said Dominic Wells, senior sustainability and cost analyst at Wood Mackenzie Ltd.

Environmental Cost

The Atacama desert of northern Chile is one of the driest places on Earth, but extracting the mineral from salt flats 10 times the size of New York’s Central Park and processing it requires a lot of water. According to BloombergNEF, it can take about 70,000 liters of water to make one ton of lithium. Mining spodumene is energy intensive and together with shipping the concentrate to China for refining can emit 3.5 times more carbon dioxide than lithium extracted from brine, according to Wood Mackenzie.

“There’s a lot of dirty things happening in producing these materials,” said Steven Vassiloudis, chief executive officer of Novalith, which is working on a system that would streamline processing of spodumene and absorb carbon. “Hard-rock lithium has such a high carbon footprint because of the energy requirement” and the many steps needed in conventional processing.

Automakers are wading in to protect the “green” image of their electric cars. BMW and a group backed by German automobile giants including Daimler AG and Volkswagen AG and have begun separate investigations into water use and production methods in the South American salt flats.

Companies are pursuing new technologies to lower expenses, cut water use and green their operations. Charlotte, North Carolina-based Albemarle Corp., the world’s biggest lithium producer, is seeking responsible mining certification for its operations in Chile and said it will reduce the intensity of freshwater use by 25% by 2030 in areas of high water risk.

“Producing lithium to use as little electricity and water is a critical goal,” said Ken Hoffman, senior expert at McKinsey & Co. “Coming up with one or several of these novel ways to produce ‘green lithium’ will be vital to the long term success of this industry. Whomever is able to deliver this technology, they should see very strong returns.”

That prize has spawned a raft of startups. Many are pursuing direct lithium extraction, a term used to describe ways to chemically capture lithium compounds that would speed up production.

“DLE can massively increase supply,” said Hoffman at McKinsey who estimates the technology could come online as soon as late next year. “You don’t need two years of drying lithium out from brine. And instead of getting about 40% of lithium out of the brine, you can get more than double the amount.”

If they succeed, it will still take time to catch up with demand.

“Even if DLE happens, we are still far behind the car companies’ EV plans for at least a decade,” Lowry said. “DLE has to be customized. It’s not a one-size-fits-all technology.”

Albemarle, which carries out its own research, said DLE so far has shown to be “typically less economic and less sustainable than conventional brine resources.” The company said it continues to investigate DLE and other processes to meet sustainability goals.

Alternative Batteries

The environmental and supply issues have prompted companies to look for alternatives to the lithium-ion battery, including hydrogen. But none have come close to supplanting lithium in the all-important passenger car market, and most are years away from commercial viability.

“Lithium-ion will remain the dominant battery technology, at least up to 2035,” said BloombergNEF’s Ampofo. “Automakers will potentially have to become miners to help develop and scale up some of these next generation lithium extraction technologies.”

Lithium-ion batteries fall into a sweet spot that balances high energy density and safety. The mineral is the least-dense solid element with the greatest electro-chemical potential and a very low melting point, producing an excellent energy-to-weight performance.

Ulderico Ulissi, battery research lead at London-based Rho Motion Ltd., an energy transition researcher, predicts that solid-state and sodium-ion batteries could eventually challenge lithium-ion packs in some applications in the second half of the decade. “EV qualification, however, is a lengthy process and scaling up manufacturing of new technologies can bring several challenges.”

Recycled Cells

Another potential source of lithium is from recycling old batteries, a practice that could meet 16% of annual demand by 2035, according to BloombergNEF. But battery retirements are only set to surge after 2030. “Basically, there’s just not enough batteries to be recycled right now,” said McKinsey’s Hoffman, adding that recycling presents its own environmental problems. “There is no great way to recycle a battery today.”

One roadblock to investing in output is that not everyone is convinced that the market will remain undersupplied and miners don’t want to be burned again by the kind of glut that caused prices to slump in 2018.

The upshot is that the lithium crunch isn’t likely to go away soon, leaving an industry that exists because of the need to protect the environment with little option but to ramp up output as fast as possible, even with a supply chain that spews emissions and guzzles scarce resources.

“Yes, it helps to be green,” said Perks at Benchmark. “But right now, we need all the lithium we can get.”

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.