About three weeks after Russian troops invaded Ukraine, Indonesian housewife Liesye Setiana was forced to close her banana chip business as cooking oil supplies dried up across the country.

Millions of consumers and small business owners in the world’s fourth most populous nation have been rattled for months by skyrocketing cooking oil prices.

As the war between the two major grain and sunflower seed producers sent jitters through global markets, many producers rushed to shift their goods abroad to cash in on soaring rates.

Setiana would travel to a supermarket over an hour from her remote East Java village of Baruharjo to buy a daily eight-litre batch of palm oil that could keep her business alive.

But the 49-year-old mother of two would be turned away, with sellers heavily rationing the commodity used in products ranging from cosmetics to chocolate spreads.

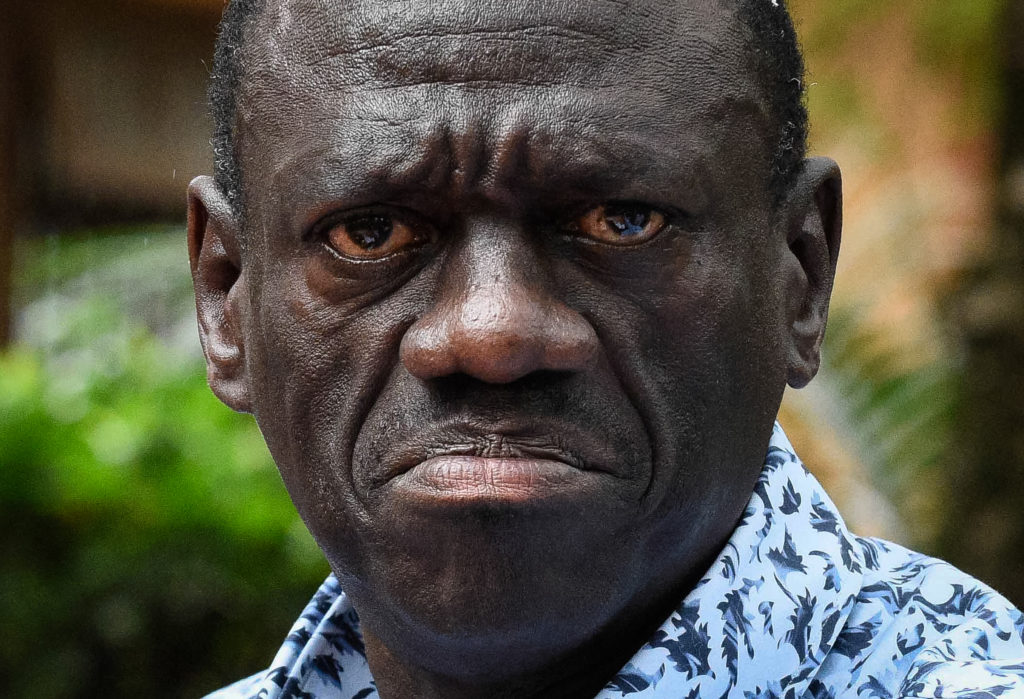

“I was fuming and told the employees that I really need the cooking oil for personal use, not for hoarding,” said Setiana, who used to make up to 750,000 rupiah ($52) a day selling her savoury yellow snack.

“How come we have cooking oil shortages when Indonesia is the world’s top palm oil producer?”

Her battle for supplies is just a snapshot of the cooking oil crisis that has spurred hours-long queues of residents with jerry cans in hand across Indonesia’s most populous island, Java, and others such as Borneo.

Two people died in March from exhaustion — including one who had queued at three different supermarkets, according to local media — as they waited in searing heat to get their hands on a product that rose to 20,100 rupiah a litre at its height.

– Counting costs –

Indonesia produces about 60 percent of global palm oil supplies, with one-third consumed domestically. India, China, the European Union and Pakistan are among its major export customers.

The squeeze on cooking oil at home forced the Indonesian government to impose a now-lifted ban on exports last month, easing prices and shoring up domestic supplies.

But at the end of May, the price of bulk cooking oil, the most affordable in the country, still hovered at about 18,300 rupiah per litre on average, above the government’s target of 14,000 rupiah, according to official data.

The price spike has left many with difficult decisions to make.

Sutaryo, who like many Indonesians goes by one name, runs a tempe chip business out of his home in South Jakarta. He was forced to jack up his prices and lay off four employees to stay afloat.

“After the surge of cooking oil prices, we have to be smart in calculating our production cost. Our consumers are left with no other choice but to accept a higher price for our kripik tempe,” he said, referring to the traditional soy-based crackers.

With demand yet to recover, production at Sutaryo’s home factory has slid from 300 to 100 kilogrammes a day, and daily revenue is down to six million rupiah from 15 million before the pandemic.

About half-a-dozen workers cut thin slices of tempe before throwing them into frying pans of hot oil, letting them sizzle until crispy.

It is a far cry from the hustle and bustle of the business’s pre-pandemic peak, said Sutaryo, when he had workers frying tempe chips outside for lack of space.

– ‘Significant’ impact on poor –

Cooking oil prices were already on the rise in 2021, but the impact of Moscow’s assault has driven them to record highs, said Mohammad Faisal, executive director of the Center of Reform on Economics (CORE Indonesia) think tank.

The government is now moving to secure even more supplies at home, meaning there is unlikely to be a repeat of the spike seen after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, he said.

But while prices may come down in Indonesia’s towns and cities, they will stay high for those living in rural and remote areas like Setiana.

“For lower-income people, the impact is significant because, at the same time, there are increases in the prices [of other commodities],” Faisal told AFP.

With local prices unlikely to fall, and with little money coming in since her husband was laid off, Setiana now has other worries — like no longer being able to afford school fees for her children.

“If prices of staple goods go up, we have little left for other expenses.”