(Bloomberg Businessweek) — Alyssa McKay used to work part-time at a frozen yogurt store in Portland, Oregon, making minimum wage to cover her college tuition. Now the 22-year-old earns more than $100,000 a year on the short-video platform TikTok. Brands like Coach, Netflix and Amazon Prime Video pay up to reach her 9 million followers, mostly teenage and pre-teen girls who wouldn’t dream of visiting Facebook.

“TikTok definitely 100% changed my life,” says McKay, who recently moved into her first apartment with her dog.

The most downloaded app of 2021, TikTok has surged to a billion-plus global users, who consume an infinite feed of short clips delivered instantly by algorithm. While the platform has long helped creators like McKay step to the center of the attention economy, the company is only now starting to cash in on all that popularity.

TikTok raked in nearly $4 billion in revenue in 2021, mostly from advertising, and is projected to hit $12 billion this year, according to the research firm eMarketer. That would make it bigger than Twitter Inc. and Snap Inc. combined — three years after it started accepting ads on the platform.

“It’s definitely a threat to Google and Facebook,” said Pieter-Jan de Kroon, chief executive officer of the online ad firm Entravision MediaDonuts. “TikTok is starting to command a percentage of the media budget that’s more in line with its audience size.”

Alphabet Inc.’s Google and Facebook, now Meta Platforms Inc., are the giants of online advertising, a duopoly so powerful they have been hit with antitrust complaints in the US, the UK and the European Union. TikTok and parent ByteDance Ltd. is shaping up to be the most serious threat to that chokehold since the pair rose to power over the past two decades.

With a billion monthly active users, TikTok is still smaller than Facebook (2.9 billion) and Instagram (2 billion), also part of Meta. Yet TikTok’s programming is proving unusually compelling: Its average user in the US now spends about 29 hours a month with the service, more than Facebook (16 hours) and Instagram (8 hours) put together, according to mobile researcher Data.ai. Scott Galloway, a professor at New York University Stern School of Business, has likened the service’s addictiveness to opium.

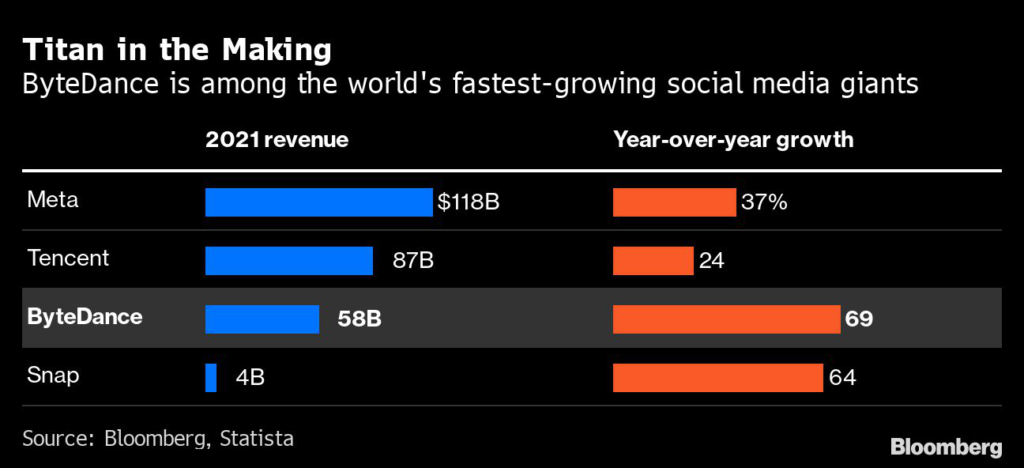

This isn’t beginner’s luck. ByteDance, TikTok’s parent, has been developing apps with algorithms for recommending just the right video clip or news story ever since Zhang Yiming founded the company ten years ago. The Beijing-based firm built a Chinese version of the TikTok platform, Douyin, that already has more than 600 million users and a battle-tested business model. ByteDance’s revenue hit an estimated $58 billion last year and its growth is faster than any other major social network.

TikTok is starting to show the profit potential in countries like the US. The company is now charging as much as $2.6 million for a one-day run of a TopView ad — the first thing that pops up on users’ feed when they open the app — roughly four times what it charged a year ago, according to a document reviewed by Bloomberg News. A 30-second Super Bowl ad runs about $6.5 million — but TikTok can charge that rate every day.

The ByteDance model goes beyond advertising. TikTok is diversifying into music distribution, game publishing and Twitch-style subscriptions. It’s also edging into e-commerce, blurring the line between social media and online shopping in ways that could challenge Amazon.com Inc. The video-sharing platform now lets merchants set up digital stores in countries like Britain, Indonesia and Thailand, where millions of users purchase products directly inside the app without any involvement from traditional e-commerce.

“TikTok is TV for Gen Z,” said Jo Cronk, president of marketing firm Whalar. “If you want your brand, your product, your service to get attention with Gen Z, that’s just a non-negotiable today.”

Read ByteDance founder Zhang Yiming’s first interview with foreign media

Mark Zuckerberg is starting to sound a little worried. The Meta co-founder blasted his Chinese rival for censorship in 2019 and later told Congress that hindering American innovation would only help Chinese companies like TikTok, perhaps to blunt antitrust scrutiny.

Then in February, Meta reported disastrous earnings that triggered a $230 billion stock wipeout. Zuckerberg name-checked TikTok no fewer than five times in a post-earnings call. The primary thing he flagged for recovery was to spend more resources on Reels, essentially a TikTok copycat.

“This is really telling that it was the first time that Mark Zuckerberg called out a competitor like that several times on a call,” says Avi Ben-Zvi, a vice president at ad agency Tinuiti. “The competition from TikTok stands out as the No. 1 challenge.”

In a sign of the rivalry, Meta allegedly hired political consultants to run campaigns against TikTok in the US, including op-eds and letters to regional news outlets targeting the app. In one example, the firm paid by Meta spread rumors of a “Slap a Teacher TikTok challenge” to local media, even though no such effort existed, the Washington Post reported in March.

Executives at Meta are now trying to quickly learn and apply lessons from TikTok’s success, with the hopes of reviving their growth, especially with a younger audience. Both Facebook and Instagram have been aggressively pushing users to Reels, promoting videos heavily in feeds even if people haven’t chosen to connect with such content.

Meta declined to comment for this story, as did Google.

Zuckerberg Is So Worried About TikTok He’s Blowing Up Instagram

TikTok’s road to monetization really began under Donald Trump. The 45th president of the United States targeted the app as part of his anti-China political strategy, threatening to ban the service because of alleged security risks. In the heat of the conflict in 2020, ByteDance agreed to sell a majority stake in TikTok to Oracle Corp. and Walmart Inc. — and pledged to create 25,000 American jobs.

TikTok ended up outlasting Trump and the fire sale was called off. Yet with ByteDance retaining 100% ownership, the company began to make real progress with its business model. The point person for this effort is Blake Chandlee, TikTok’s Texas-based president for global business solutions.

Chandlee, who joined the company in 2019 after a decade at Facebook, makes the case that traditional advertising is dying, and businesses will die if they keep putting money into the same old TV shows or social networks.

“When people think branding, they still think TV. And I just think that’s wrong,” Chandlee says in an interview from Cannes Lions, a five-day festival for the advertising community in the French resort town. “We should be purposely disrupting television.”

Chandlee and his team — a fleet of engineers, data analysts and sales reps in the thousands in cities from Shanghai to Austin and Warsaw — work with brands to partner with influencers like McKay and create viral challenges, goofy camera effects and immersive full-screen videos. “Don’t make ads. Make TikToks,” their motto goes.

Advertisers are now making TikTok an integral part of their media strategy and budget. “Two years ago, they were really in the testing experimental mode before the political winds shifted,” says Ryan Detert, CEO of the Influential marketing firm. “Now it’s beyond testing, and it’s like how much money we should be pumping into this platform.”

Richard Henne, co-founder of clothing store Ivory Ella, says his firm uses TikTok to attract middle-school and Gen-Z girls, key target customers it’s not getting from older social networks. While the firm has been spending a quarter of its social marketing budget on Facebook and Instagram, he’s now trying to “lower that number as much as possible, as soon as possible because they’re obviously losing their grip on the marketplace.”

TikTok has an edge against Meta that Apple Inc. helped solidify. Last year, the Cupertino, Calif.-based company updated its iPhone operating system so that users have to opt in to let apps like Facebook track their activities as they used other software on their phones. Most users decided not to let Meta track them, a change Zuckerberg has blamed for financial troubles like those in February.

TikTok, it turns out, isn’t relying so much on that kind of tracking data. Its artificial intelligence discerns a user’s likes or dislikes largely from activities on the platform, picking up on how long you watch, say, a cat video, a skateboarding clip or lip-synced dancing. TikTok’s algorithms can then match up users with not just content, but advertising too.

Take Oanh Nguyen, a 31-year-old in Los Angeles who’s built a 13-million-person fanbase on TikTok since Covid put her hair salon out of business. Nguyen makes comedy skits on her account “Moontellthat” and in one of her sponsored videos, the creator rushed to wash her hair and dress up for a big family gathering, only to find out her boyfriend was playing a prank on her. Proctor & Gamble paid the couple $20,000 to feature its Pantene shampoo in the 30-second production, she says, which has 5 million views.

It’s the Gen Z version of the product placement that’s been around for decades — think Nike in Back to the Future or FedEx in Cast Away. TikTok set up a $200 million fund in 2020 to pay creators to get views, and pledged to grow the pool to $1 billion in the US over the next three years.

YouTube, Instagram and Snapchat later followed suit. Every major social network is now trying out short videos on their main platforms, raising the competition to surreal intensity. At Meta, engineers are rewriting the algorithms for Facebook and Instagram to surprise and delight people with videos they didn’t know they wanted to see — the very core of TikTok’s appeal.

Such moves by Meta are risky, but deemed necessary; Facebook, the top moneymaker, is suffering from an aging audience. Lower-than-expected demand from advertisers, which Meta attributed to stress factors like inflation, the supply crunch and the war in Ukraine, doesn’t seem to be affecting TikTok as much because it just turned on the money machine. And Meta needs its strong revenue growth to continue, in order to fund Zuckerberg’s futuristic immersive internet, called the metaverse. It’s an effort that will lose “significant” money in the near term, Zuckerberg has said.

The cutthroat battle has been a bonanza for creators like Maria Luisa Van Zwieten. The 29-year-old Dutch cosplayer earns up to ten grand from brands enlisting her to make TikTok videos in a good month — and now she can make an equivalent amount by posting the same clips on Reels.

“There’s less work for me, but double the earnings, so I was like all good,” Van Zwieten says.

Chandlee and his team keep experimenting. In May, TikTok started to allow top creators to get revenue share from the ads placed in between their video content, a move that mimics YouTube’s long-running program with vloggers. TikTok also started to sell its TopView ads by clicks and impressions instead of just one-day bundles, allowing more targeting and budgeting options for clients accustomed to similar options with Facebook.

Marketers and ad agencies say Meta still offers better products in media buying, the good old ad placements that translate directly into purchases or app installs. Fabian Ouwehand, Munich-based founder of the Many Creators agency, says many companies simply haven’t bought the idea of making TikToks instead of ads.

“Still I’m in these calls with big companies and they say, ‘yeah, but we want to create something like a TV commercial.’ And then the TikTok team is always so frustrated,” says Ouwehand, who now heads the social e-commerce unit for German home shopping network HSE after the firm acquired his agency. “Because many still don’t get it, still, how to create a TikTok video.”

ByteDance’s Zhang has called the blending of entertainment and buying his “next major breakthrough.” In 2020, Douyin, the Chinese TikTok, hosted $26 billion of e-commerce transactions in its first year of offering shopping in the app and that business tripled in size over the past 12 months. The idea is to take care of as many steps of a purchase as possible, with in-app stores, customer support and built-in payment functions.

TikTok has teamed up with Shopify Inc. to let merchants embed their web shops into videos on the platform. The transactions have been processed by those third-party sites, similar to on Facebook Shops. But more recently TikTok took an approach that mimics Douyin more closely: since mid-2021, it rolled out in-app stores with a more frictionless experience in countries including Britain, Indonesia, Singapore and Thailand.

“The journey to purchase something is very, very easy. It’s like one click away,” says Fauza Istighfareva, a Jakarta-based manager with digital agency Leverate Media.

TikTok plans to grow its e-commerce gross merchandise volume to $2 billion this year and $23 billion in 2023, according to a person close to ByteDance who asked to remain anonymous while discussing private information. Indonesia, one of its most populous markets, will make up a big portion of that target, the person says.

“When it comes to monetization, Douyin is typically two or three years ahead of TikTok, including in e-commerce,” says Zheng Yi, a partner with Zoo Capital, a Chinese venture firm investing in tech. TikTok’s move into e-commerce, he adds, “could be a big game changer.”

All of this had ByteDance on track for a blockbuster initial public offering — up until about a year ago. The company’s valuation rose to more than $350 billion in private transactions last year, Bloomberg News reported, making it the most valuable startup in the world, ahead of SpaceX and Stripe Inc.

But its prospects have taken a hit from the plunge in technology stocks worldwide and from China’s crackdown on its private sector. President Xi Jinping’s administration has rolled out sweeping reforms against the country’s internet giants, including Alibaba Group Holding Ltd., Tencent Holdings Ltd. and ByteDance.

Over the course of the past year, Beijing’s hardline policies led ByteDance to shut down most of its online education operations, offload a stock trading app and disband its venture investment arm. Communist Party officials even unveiled a 30-point guide for regulating the algorithms of services like Douyin. Zhang, the first Chinese founder to create a truly global internet player, stepped down as CEO and chairman last year amid the political pressure.

China Plans Control of Tech Algorithms U.S. Can Only Dream Of

Politics remains an enormous risk in the US too. While the Biden administration scrapped efforts to ban TikTok, China hawks continue to view it as a potential security threat. On June 17, Buzzfeed News reported that China-based ByteDance employees had repeatedly accessed nonpublic data about US TikTok users as recently as this January. The same day the story ran, TikTok announced that “100% of US user traffic” is being routed to Oracle servers in Texas.

ByteDance has been shifting more attention to TikTok as uncertainty mounts at home. The Chinese company hired Chew Shouzi from handset maker Xiaomi Corp. last year and then promoted him to TikTok CEO. Other key execs who made the switch from ByteDance to TikTok include Zhu Wenjia, the coding wizard behind its algorithms, and Bobby Kang, who led Douyin’s live-streaming commerce business. There’s been speculation ByteDance may look to spin off TikTok and set it up as a non-Chinese business, though the political risks of such a move are enormous.

The intrigue is largely lost on TikTok’s stars. Creators like McKay worry less about who’s calling the shots in Beijing or Washington than creating just the right skit for a viral hit. After graduating this summer, she is trying her hand at acting and landed the lead in a film called Cake (town), “a modern day rust belt Romeo and Juliet.”

“I’m still going to continue doing short-form content even if my acting career takes off.” says McKay. “I just love sharing my life, so I would always do it regardless.”

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.