(Bloomberg) — In the spartan offices of his small private investment firm, Raj Rajaratnam, former inmate 62785-054, is searching for his next big trade.

All is quiet inside the townhouse in Manhattan’s East 50s — 200 miles and a world away from the federal prison where he served seven-and-a-half years for insider trading.

It’s been three years since the former hedge-fund magnate was freed from FMC Devens, the medical prison west of Boston where he did time with Ponzi schemer Nicholas Cosmo, AKA, the “mini-Madoff”, among others.

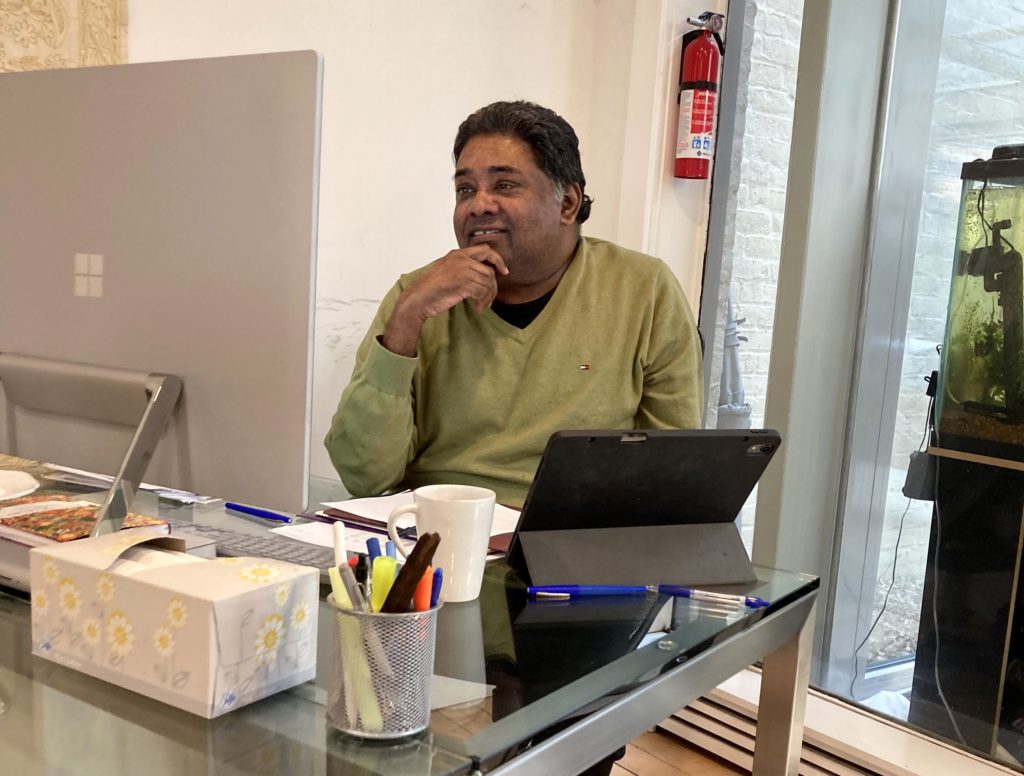

His new surroundings are undoubtedly a step up. But they’re surprisingly modest for the man known as Raj-Raj, the high-rolling trader who became the Ivan Boesky of his time. Nothing about this unassuming building might suggest this is where Rajaratnam — “Sunk by Greed” and “bound for brig,” the New York Post trumpeted 11 years ago — hopes to stage a comeback, maybe in more ways than one.

In his heyday at his multibillion-dollar Galleon Group LLC, computer screens crowded his huge, curved desk, monitoring markets around the globe. Here at Synamon Global LLC, Rajaratnam works at a utilitarian glass-topped table that looks as if it might’ve come from Ikea. A leather satchel is tossed on the blond-wood floor behind him. A beige tapestry hangs on one white wall, a red fire extinguisher nearby. The fish tank in the adjoining sunroom-workspace could stand a cleaning.

Rajaratnam, 65, is less fleshy than he was in his days as tabloid fodder. His temples are graying. The neat mustache is gone, as are the rimless glasses, but the gap-toothed smile is the same as ever. He peers into his monitor and pecks at the keyboard. Barred for life from managing other people’s money, and with Galleon long since shut, Rajaratnam spends his days tending his considerable personal fortune in obscurity. With about 18 people working or consulting for his family-office firm — the name “Synamon” echoes the spice most associated with his native Sri Lanka — he’s trading stocks, investing in real estate, whatever catches his eye.

As much as anything, Rajaratnam is looking for a shot at redemption. He’s embarked on a long, lonely quest to rehabilitate his reputation, or at least indict the legal system that indicted him. Ever since federal agents showed up at his pricey Sutton Place apartment in 2009, he’s maintained his innocence. His case riveted Wall Street, and with reason: He ended up being convicted on all 14 counts of securities fraud and conspiracy and sentenced to 11 years, one of the the harshest penalties the US has ever levied for insider trading. It was the first major insider trading case in which the government used wiretaps, a tactic often used against organized crime and drug traffickers.

Today Rajaratnam insists he doesn’t want to relitigate his case. But he’s been doing that a lot lately in media interviews and in a book, “Uneven Justice: The Plot to Sink Galleon,’’ published in December. Like Michael Milken, a symbol of the greed-is-good 1980s who has successfully refurbished his reputation and been re-embraced by the global business elite, Rajaratnam is also using his wealth for various philanthropic efforts, particularly in his native Sri Lanka.

But make no mistake: Raj Rajaratnam is unrepentant. He says he was the “fall guy” for the feds’ failure to convict any prominent bankers following the 2008 financial crisis. “I was entrapped, framed, unlawfully wiretapped, surveilled, and then made to endure a brutal and very public media lynching,” Rajaratnam writes in “Uneven Justice.” Federal agents and prosecutors crossed legal lines to convict him, he says. Threatened with prison, employees and business contacts testified against him to save themselves, he says.

At FMC Devens, where he was sent because he has diabetes and kidney disease, he did time with murders and sex offenders – he says he tried to avoid them – and befriended drug dealers and white-collar crooks. Some fellow inmates tried to extort money from him. “That was not going to happen with me,” he says.

“This is a huge infrastructure that has to change,” Rajaratnam says of the criminal-justice system.

That’s not quite the way federal prosecutors saw things. Government authorities called Rajaratnam “a billion-dollar force of deception and corruption on Wall Street.” Tapping a network of informants across swaths of corporate America, he illegally used inside information to trade stocks such as Goldman Sachs Group Inc., Google, Intel Corp. and Hilton Worldwide Holdings, prosecutors said. His trading generated profits or avoided losses of $72 million, not quite $10 million for each year he served in prison.

The explosive case exposed the trafficking in illicit information at the highest echelons of American finance. Roughly a hundred other people were eventually ensnared by insider trading cases. Most pleaded guilty or, like Rajaratnam, were convicted by a jury. Among those who went to prison were Rajat Gupta, former global head of McKinsey & Co. and former board member for Goldman Sachs, who blamed Rajaratnam for his downfall. The two were later reunited at FMC Devens, where Rajaratnam says they played bridge and Scrabble together. (Gupta was convicted of passing tips to Rajaratnam related to Goldman Sachs and was sentenced to 2 years; he has long maintained his innocence.)

“Yeah, we were civil to each other,” Rajaratnam says of Gupta.

Rajaratnam has been far less charitable toward Preet Bharara, the former US attorney who spearheaded the government’s sweeping crackdown. Some celebrated Bharara as the Sheriff of Wall Street for aggressively going after hedge fund managers. Others accused him of letting Wall Street off the hook for the financial crisis. To hear Rajaratnam tell it, Bharara used the power of his office to win at all costs and advance his own career. He mentions Bharara 325 times in his 333-page book.

Bharara today says he doesn’t care what Rajaratnam thinks. In an email, the former prosecutor called the hedge funder he put away possibly “the least sympathetic defendant ever.”

Says Bharara: “Raj Rajaratnam was a privileged billionaire who engaged in massive insider trading, and there was an avalanche of evidence to prove it.” Bharara pointed to Rajaratnam’s failure to win over jurors and judges, despite an aggressive and costly defense.

“Whatever fairy tales he may now tell to rehabilitate his reputation or settle scores or peddle his book, Raj Rajaratnam was and is guilty. Period,” wrote Bharara, who was fired by Donald Trump in 2017.

Still, like Milken, Rajaratnam may have another act yet. Anita Raghavan, a former Wall Street Journal reporter who wrote a book about Rajaratnam and Gupta, says that in all likelihood Rajaratnam is still a billionaire. She calls his book a “selective retelling” of the Galleon affair and says there was ample evidence at trial to convict Rajaratnam. But wealth begets wealth, and also influence. In the waning days of the Trump administration, Milken received a presidential pardon.

For his part, Rajaratnam won’t say if he’s still a billionaire.

“Yes I am, in many currencies — rupees, lira, pesos,” he jokes.

Back at Synamon, Rajaratnam is working with his small staff to spot investment opportunities

“We invest in real estate, as well as in the stock market,” he says. “And so I come to work every day. Rather than having hundreds of investors, we have one investor.”

Galleon specialized in technology and healthcare, waters Rajaratnam is still plying today. Synamon’s investments include companies in medical technology, cloud computing, cybersecurity and clean energy, including electric vehicles. Its real estate investment business is buying residential properties in New York and in 10 states across the South, he says. His employees include recent college students who are working for him as analysts. The US staff is spread among New York, Pittsburgh and San Francisco. A team in Sri Lanka covers e-commerce.

Ean Renaud, 23, has been working for Rajaratanam since a chance, five-minute encounter with him last year while meeting with another trader. Renaud is a former competitive swimmer who says he dropped out of college to launch a clothing line, then worked at a start-up and traded stocks for his own account. As a rookie analyst, he’s thrilled to benefit from Rajaratnam’s years of experience in finance.

“You can kind of tell, he’s grinning and he enjoys thoroughly what he’s talking about,” Renaud said. “He hopes to see the excitement return from the other person he’s teaching.”

In an online meeting, the two discuss a recent downturn in the shares of Chinese electric car makers.

Rajaratnam seems delighted to hear from Renaud that one, XPeng Inc., is developing a flying car. Another analyst briefed Rajaratnam on Procept BioRobotics Corp., which sells equipment for robotic surgery.

After the call, Rajaratnam’s office is quiet again. He takes a few M&M’s from a bag. “I really have no regrets about the decisions I made,” he said. “I’m not looking back with bitterness.”

Whether Rajaratnam can pick himself up after such a spectacular fall is anyone’s guess. But he still has the money to try. The year was arrested, Forbes estimated he was worth $1.3 billion. He says legal fees and fines cost him $200 million. As for what he’s worth today? “Subtract that from whatever number you think I had,” he says with a laugh.

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.