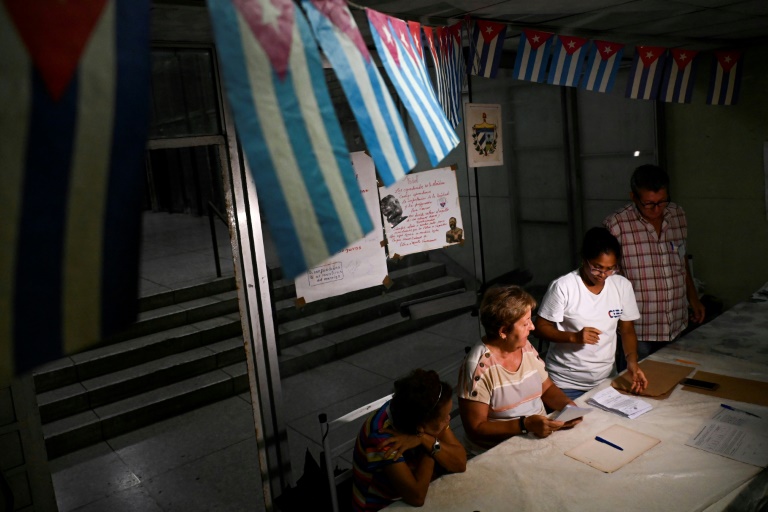

Electoral authorities count ballots at a polling station in Havana, on September 25, 2022

Cubans voted to legalize same-sex marriage and adoption as well as surrogate pregnancies in a referendum over the weekend, the communist country’s electoral officials said Monday.

Preliminary results indicate an “irreversible trend,” with almost 67 percent of votes counted so far in favor of the government-backed change, electoral council president Alina Balseiro said on state television.

“The Family Code has been ratified by the people,” she said.

President Miguel Diaz-Canel tweeted: “Yes has won. Justice has been done.”

The updated code represents a major shift in a country where machismo is strong and where the authorities sent LGBTQ people to militarized labor camps in the 1960s and 1970s.

Official attitudes have since evolved, and the government conducted an intense media campaign in favor of the overhaul, which will replace the country’s 1975 Family Code.

The new code permits surrogate pregnancies as long as no money changes hands, and legally recognizes same-sex adoptions, as well as several fathers or mothers in addition to the biological parents.

It defines marriage as the union between two people, rather than that of a man and a woman, while also boosting the rights of children, the elderly and the disabled.

“In the end we won!” wrote LGBTQ rights activist Maykel Gonzalez on Twitter.

“It settles a debt with several generations of Cuban men and women whose family projects have been waiting for this law. From now on we will be a better nation,” said Diaz-Canel.

– ‘Punishment vote’ –

According to the National Electoral Council, 74 percent of Cuba’s 8.4 million eligible voters cast a ballot with 3.9 million valid votes counted so far in favor and only 2.0 million against.

Turnout, however, was well below the last referendum when a new constitution was adopted in 2019 with 90 percent of people casting a ballot.

It is also the lowest percentage the communist government has received in a vote since Fidel Castro’s 1959 revolution.

Diaz-Canel acknowledged Sunday that “for such complex issues, where are is a diversity” of motives, people might cast “a punishment vote.”

Experts had predicted before the vote that many Cubans would use the referendum as a means to express their disapproval of the government.

Dissidents had called on citizens to reject the code or to abstain.

Cuban political scientist Rafael Hernandez said adopting the new family code was “an effective step in the direction of social justice” and that this was the “most important” legal protection for human rights since the revolution.

The law required 50 percent voter approval to be adopted.

The referendum came amid the country’s worst economic crisis in 30 years that was exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic.

It was the first time an issue other than a constitutional change had been put to a public vote in Cuba.

The main opposition to the law’s adoption came from Protestant and Catholic churches, the latter of which blasted the changes as “gender ideology.”