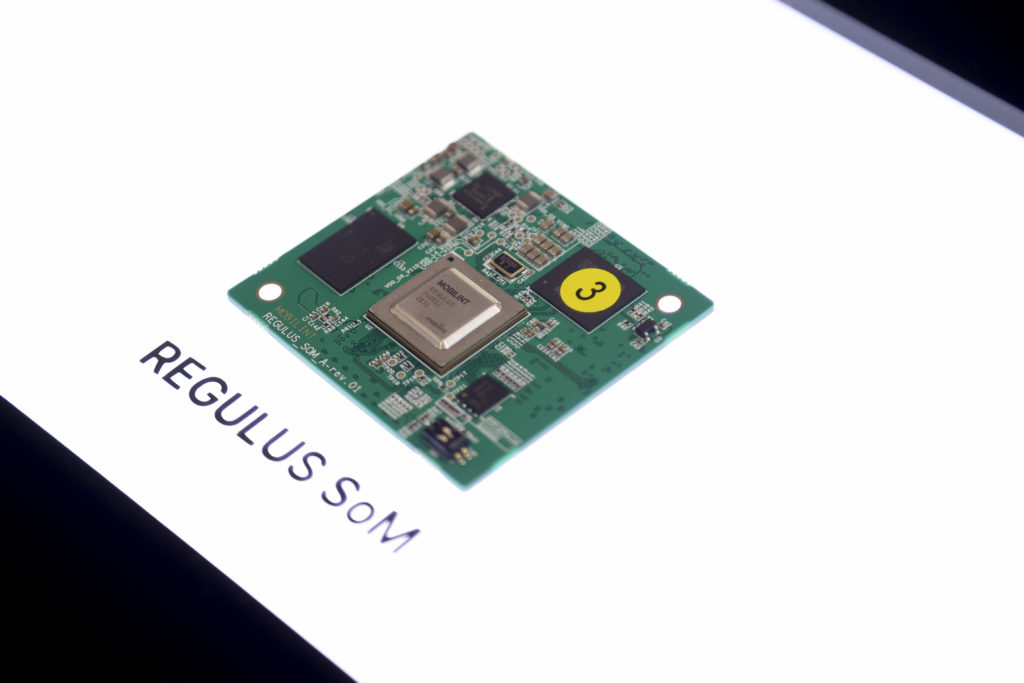

Poll workers handle ballots for the US midterm elections, in the presence of observers from both Democratic and Republican parties, at the Maricopa County Tabulation and Elections Center (MCTEC) in Phoenix, Arizona on October 25, 2022

Many are burning out, others fear for their safety: conspiracy theories born in the 2020 election are fueling harassment of poll workers across the United States — complicating their work and stoking fears of violence in the November 8 midterms.

Egged on by baseless claims of fraud from former president Donald Trump and others, many voters are taking matters into their own hands, with officials warning of real consequences for the democratic process.

“The only problems we have had, honestly, have been dealing with misinformation,” said Richard Keech, deputy registrar in Loudoun County, Virginia, outside Washington.

Voters streamed into the county Office of Elections when AFP visited on October 28, casting ballots early in a swing state where Republicans hope to pick up seats in Congress.

One asked if the voting machines were connected to the internet, echoing a huge, false narrative that spread online in 2020. Voting machines are not typically online — and thus are not vulnerable to hacking while polls are open.

However benign, questions like that can slow election workers down. Others are less innocent, veering into harassment.

Since August, Loudoun County has fielded more than 200 freedom of information requests about voting equipment and procedures, the highest number ever received — sapping precious resources.

A local group of “digital warriors” circulated a video falsely claiming county officials were storing photos of ballots.

“Within 24 hours, we had voters showing up at the front counter insisting to see the picture of their ballot to show that their vote was counted properly,” said Keech, who has worked for the elections office for over a decade.

In Arizona, ballot watchers inspired by a popular conspiracy film about the 2020 election have staked out and recorded activity at drop boxes.

In other battleground states such as Florida and Michigan, the Republican National Committee has recruited poll workers from groups that deny President Joe Biden’s 2020 victory was legitimate.

And in Pennsylvania, poll officials say they are concerned for their safety.

“There’s definitely a gravity weighing on us just kind of knowing what’s happening in other counties,” said Dori Sawyer, voter services director in Montgomery County, near Philadelphia. “Kind of, you know, wondering: When is it our turn?”

– ‘Threats and harassment’ –

Despite reports about vulnerabilities in electronic voting systems, Jen Easterly, director of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, said last month that the agency is “not aware of any specific or credible threats to compromise or disrupt election infrastructure.”

That said, “the current election threat environment is more complex than it has ever been,” she told reporters, pointing to potential harassment targeting officials and “insider threats” from poll workers.

After Trump’s presidential election loss, local officials became the target of unfounded claims about malfeasance. Some had to go into hiding due to death threats, as they recounted in congressional testimony.

The US Department of Justice has pledged to crack down on such threats going into the midterms, but the intimidation has already taken a toll.

“It’s kind of exacerbated the tensions around elections in a way that I’ve never seen before — and I’ve been doing this for almost 20 years,” said Tammy Patrick, senior advisor to the elections program at the nonprofit Democracy Fund and a former Arizona election official.

“We have seen states where a quarter of their election officials, a third of their election officials have resigned.”

According to Keech, about a third of the poll workers in Virginia’s Loudoun County are new this year. Other US states have not replaced those who resigned after 2020, and the job for the top election official in Fulton County, Georgia — which includes Atlanta — remains empty.

Experts warn this attrition spells trouble, as mistakes from inexperienced poll workers could be misconstrued as wrongdoing. And in some places, staffing gaps are being filled by members of election denial groups.

“Whenever you bring on a lot of temporary workers in the run-up to an election cycle, by the very nature you increase the possibility of that insider threat,” said David Levine, a fellow at the Alliance For Securing Democracy, a national security group, and a former Idaho election official.

– ‘Safeguarding’ –

Some voting processes have been changed as a result of harassment.

“We’ve made some additional physical security enhancements to our building or locations,” Keech said, including new locks at the Office of Elections.

He said Loudoun County also “further strengthened” chain-of-custody procedures for ballots.

In Montgomery County, Sawyer said she has had security briefings with local law enforcement and FBI agents. Her staff will also be present at drop boxes to explain how they are secured.

When voters call with “really intense concerns” about the election process, Sawyer said she reminds them that “we’re real people.”

“I care about democracy,” she said. “We get to choose our leaders. We kind of get to write our own destiny. I think that is worth safeguarding.”