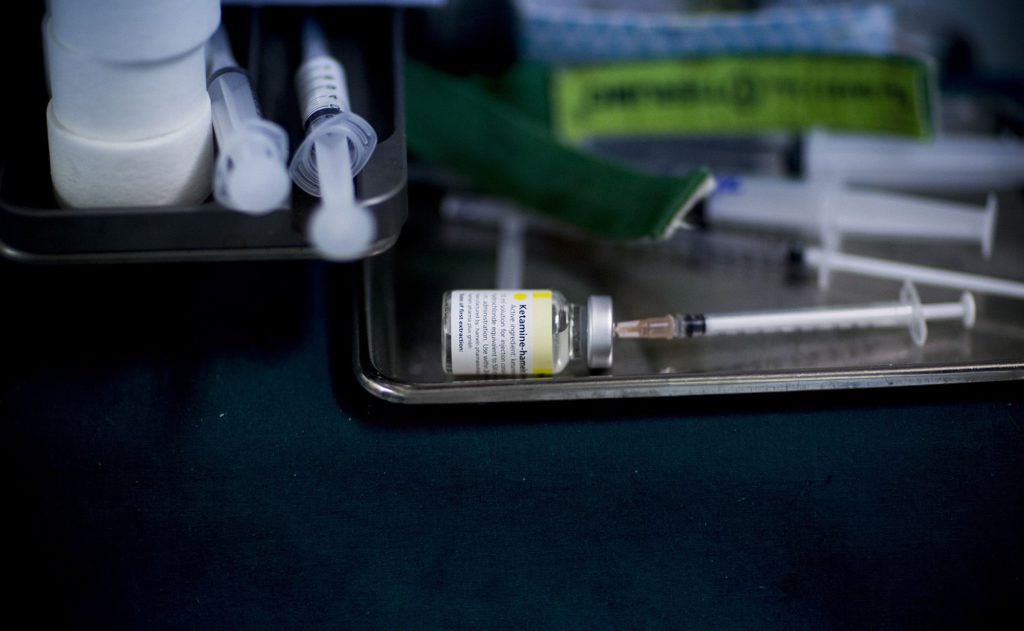

Covid regulations made therapeutic ketamine available via telehealth, but concerns about abuse could mean trouble for the startups selling it.

(Bloomberg) — A controversial depression treatment that boomed during the pandemic could become far less accessible by next year — potentially leaving patients high and dry and the internet upstarts that supply them looking for a contingency plan. Covid-era measures that allowed doctors to remotely prescribe ketamine, an often-abused drug increasingly popular for treatment-resistant depression, could unwind this spring. That could spell trouble for companies such as Mindbloom and Nue Life that will be forced to rethink their businesses amid concerns that at-home access has increased abuse of the drugs.

“I tell these folks, ‘There’s going to be a reckoning coming, and when that reckoning comes, you probably will lose everything,’” said Anthony Coulson, a retired DEA regional head who now consults for startups about controlled substances.

For the past three years, the public health emergency has temporarily suspended a 2008 law called the Ryan Haight Act that forbids the prescription of controlled substances via telemedicine. That allowed patients with depression to access ketamine — a drug originally designed as an anesthetic that also has hallucinogenic effects — without leaving their homes.

But whether the Biden administration will renew the emergency status yet again when it expires in the spring remains to be seen. Republican lawmakers including Washington congresswoman Cathy McMorris Rodgers have been actively pushing against it. If that happens, mail-order businesses might be required to make drastic changes to their business models, such as requiring patients to attend at least some in-person visits.

Making ketamine available via telehealth has had two major effects that may ultimately influence the fate of these companies. It is now wildly more accessible, with companies like Mindbloom advertising mail-order treatments to millennials via Instagram. Some companies offer sessions for as little as $167. It is also far more vulnerable to abuse: People who want to use the drug recreationally for its mind-bending effects or because they have become dependent on it can now get it more easily.

“One of the big concerns about ketamine is about its abuse liability,” said John Krystal, a pioneering Yale researcher who helped define the drug’s therapeutic potential. “If people are getting many doses at home, then the potential for abuse goes up significantly.”

One ketamine startup, Mindbloom, opened its first in-person clinic in Manhattan with much fanfare in early March 2020, promising a “spa-like setting” with zero-gravity chairs, weighted blankets and aromatherapy. Then, within weeks, the world shut down. Mindbloom had already tested at-home ketamine options, so it pivoted fully to virtual treatment, and business boomed. Mindbloom is now available in 35 states and Washington DC.

While there are still plenty of in-person ketamine clinics, the virtual business is what has caught the attention of venture capitalists. Shipping ketamine through the mail offers better profit margins and the possibility of quickly scaling. Instead of paying rent for an office, you can use software and virtual calls to guide patients through the experience. Mindbloom, which offers at-home options, charges roughly $200 per treatment. Meanwhile Polaris, a well-known San Francisco clinic, can cost up to $1250 for a three-hour session including talk therapy.

Unlike in-person patients, a patient doing at-home treatment could take more in one sitting than is prescribed, or could give the drugs away to someone else. And supervision over teleconference is less rigorous. At Mindbloom, for example, patients must do a video call ahead of their first session, but subsequent sessions are “self-led.” The patients are told they must have a monitor in the house – like a friend or family member – during a session, but Mindbloom declined to specify how that request was enforced.

Leonardo Vando, Mindbloom’s medical director, said in a statement that the concerns about at-home ketamine therapy are “speculative” and have been “raised by people whose businesses compete with telehealth.” He added that data indicates remote ketamine therapy can be effective and safe, and that “it’s important to make lower-cost, more-accessible treatment options like this available if we’re going to turn the tide of the mental health crisis.”

Julia Mirer, a physician who’s now a psychedelics consultant, including to some of Mindbloom’s competitors, said she was taught in medical school that doctors should never assume patients are taking drugs correctly. Ketamine, she’s observed, is no different. “I’ve talked to people who said, ‘My doctor sent me three sessions. It was really great, but after the second time, my wife and I took some to have fun,’” Mirer said. At its worst, ketamine can be treated like “a dependable escape,” she added. “It becomes too easy to enjoy the ketaverse.”

Often, patients start with an online appointment with a prescribing clinician. If approved, the drugs are administered virtually by often-unlicensed ketamine guides, who videoconference with patients before, after, or sometimes during their session. Mindbloom’s guides, for example, are hourly contract workers who are not required to be licensed in any way, though many of them have coaching experience. Providers are also still refining the best doses and treatment schedules for the virtual environment. And virtual clinics also face many of the same complications and criticisms as other upstarts launched to prescribe specific drugs, like Hims and Roman. With this business model, typically the company makes money if a doctor is able to treat a patient with the specific drugs the company offers. Mindbloom, for example, offers ketamine therapy, not generalized treatment for depression.

Coulson, the retired DEA agent, said that companies selling ketamine via telehealth may not be thinking of the health of their patients first. “The concerns are making money,” he said.

All of these factors mean that when the public health emergency ends — and it will, eventually — things may get complicated for businesses built around prescribing ketamine at home. Mindbloom, for one, said it is prepared to re-introduce in-person exams if needed by using partnerships with other clinics, in-home exams, or their own spaces. The company said it is also betting that telehealth waivers may remain even if the public health emergency ends. For now, the US government is extending the deadline three months at a time, with calls to end it only growing louder. Whenever regulations change, it’ll likely mean patients will have to be seen in person at least once — and that an already-tangled web of state licenses will get even knottier.

That uncertainty has left some investors wary. Dustin Robinson invests in psychedelic startups, but his firm hasn’t invested in any that depend on telehealth, he said: “I’m probably too familiar with the risks involved of what could happen.”

–With assistance from Riley Griffin.

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.