The Bank of Korea needs to see strong signs that inflation is under control before plotting any pivot away from policy tightening, Governor Rhee Chang-yong said Friday, dismissing as premature speculation about a return to easing next year.

(Bloomberg) — The Bank of Korea needs to see strong signs that inflation is under control before plotting any pivot away from policy tightening, Governor Rhee Chang-yong said Friday, dismissing as premature speculation about a return to easing next year.

The central bank came closer to the end of its tightening cycle when it raised the key interest rate by 25 basis points to 3.25% on Thursday. The BOK’s board holds a range of views on the terminal rate: three favor 3.5%, one thinks enough has been done, while two want the door kept open to going above 3.5%.

“At least in the first half of next year, we will think about when to pause and then how we’re going to handle this inflation,” Rhee said in an interview with Bloomberg TV’s Kathleen Hays. “Once we have seen strong signs that inflation is under control, then we have to think about the next trade-off.”

Citigroup Inc. and Nomura Holdings Inc. are forecasting the BOK will begin cutting rates as early as mid-2023, predicting Korea’s economy will need the policy support.

Rhee said a variety of factors will help determine the course of policy, including the Federal Reserve’s decision in December, global oil prices, Covid policies in China and credit-market conditions in Korea.

“Considering all these factors, we decided to maintain our flexibility and think about our next move probably in January,” Rhee said. “It’ll be very hard to judge where we’re going to stop or when, but our board members believe probably we can go to about 3.5%.”

The governor added that he wouldn’t be surprised if some board members changed their mind over the terminal rate. He declined to provide his own forecast, adding that he would reveal it if the board was evenly split.

It’s “premature” to discuss any rate cuts and the BOK will need strong evidence of inflation slowing to its mid-term target of a 2% range before the board can discuss the potential for easing policy, he said. The BOK’s latest forecasts released Thursday show inflation holding above 2% through 2024.

The bank has delivered a total of 2.75 percentage points of rate hikes since August 2021, including two half-point moves. The tightening helped Korea position itself earlier than most nations in the fight against asset bubbles and inflationary pressures.

However, its faster-than-usual tightening in recent months has fueled credit risks triggered by the default of a local government-backed developer.

“I think there’s excessive sensitivity,” the governor said of the credit risks. Coupled with the UK’s now-retracted stimulus, the Korean case offers a lesson for the world that “one small mistake can jeopardize the whole economy.”

Overall, Korea’s financial markets remain in good shape despite the credit rout associated with the real estate market, which stemmed from a mistake by a local province, he said. Rhee downplayed the prospect of needing to provide the kind of liquidity support seen at the start of the pandemic.

“You cannot give this heavy medicine before you try other measures,” he said.

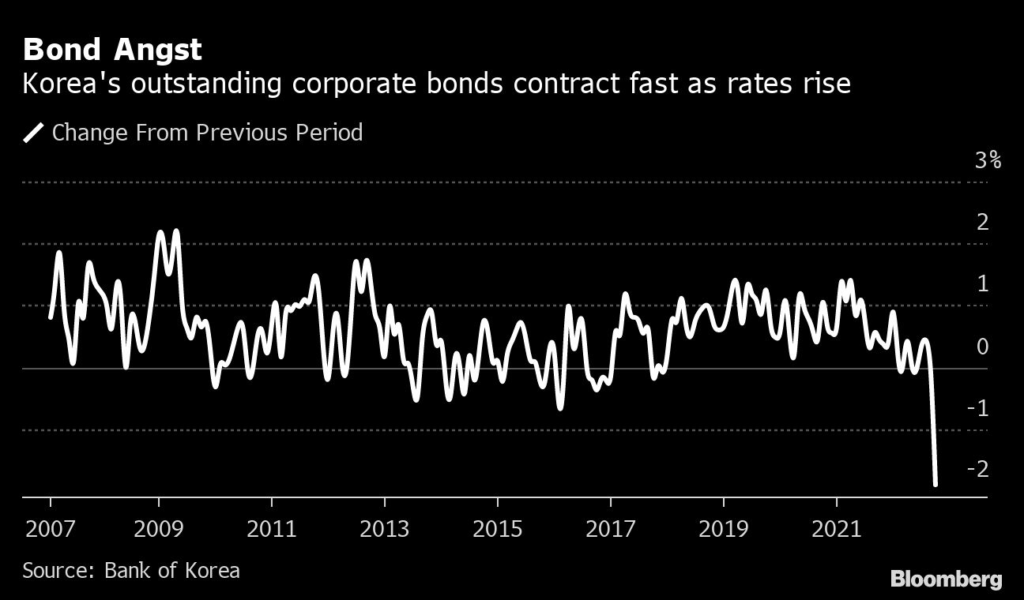

In a sign of credit strains, Korea’s corporate bond market shrank the most on record last month. Meanwhile, credit yields have kept climbing.

“I wouldn’t be surprised they are not coming down given that we are still increasing interest rates,” Rhee said.

Among other concerns weighing on Rhee’s mind are sputtering exports. Korea posted the first fall in overseas shipments in two years in October, with chip sales falling by the most since late 2019.

The BOK on Thursday projected the economy will grow 1.7% next year, sharply slower than previously forecast, while inflation is seen at 3.6%.

Inflation will stay elevated early next year, prompting the bank to “focus more on how to stabilize it,” as growth slows due to a “more severe slowdown” in Europe and the US, Rhee said. He also highlighted Korea’s heavy reliance on chip prices.

Rhee took office in April after helming the Asia-Pacific department of the International Monetary Fund, an institution that bailed out Korea during the Asian financial crisis a quarter-century ago.

While today’s Korea barely resembles the economy then, the credit rout highlighted its vulnerabilities as a nation closely intertwined with the global economy and Fed policy.

Rhee said earlier this year that the BOK may have won independence from the Korean government but not from the Fed. Recent outsized hikes reflected the urgency of keeping pace with the Fed in order to minimize the risk of capital outflows that could pummel the won.

“What I meant is that as a small open economy, the foreign exchange sector is one of the important factors in deciding monetary policy,” he said. “We are not mechanically following the US interest rate, but we are very mindful of its impact on our exchange rate.”

The Fed hikes have been harsh on the won, the worst performing currency after the yen in Asia this year. It’s made Korea’s imports more expensive and added to financial burdens for the nation’s debt-laden households.

“Korea’s leverage ratio, especially household debt, is in a relatively high range,” he said, calling it a a medium-term challenge. “You cannot deleverage in a very short period of time. That will cause many negative side effects.”

–With assistance from Jaehyun Eom and Kyungji Cho.

(Updates with rate-cut speculation, charts, further comments.)

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.