Markus Braun makes his first public appearance in court today, more than two years after his high-flying digital-payment company Wirecard AG collapsed under the weight of fraud allegations, wiping out billions in shareholder value and destroying Germany’s efforts to breed a new technology champion rivaling Silicon Valley.

(Bloomberg) — Markus Braun makes his first public appearance in court today, more than two years after his high-flying digital-payment company Wirecard AG collapsed under the weight of fraud allegations, wiping out billions in shareholder value and destroying Germany’s efforts to breed a new technology champion rivaling Silicon Valley.

The Munich Regional Court opened the case against Braun and two co-accused on Thursday in a spacious courtroom located in the Stadelheim prison, among Germany’s largest prison complexes. With more than three dozen journalists registered to follow the proceedings, the trial is set to stretch well into 2024 as the presiding five judges pours over material collected in more than 700 binders of documents.

The case will retrace the steps leading up to the early months of 2020, when Wirecard fought an increasingly futile battle to portray itself as a digital payment pioneer under assault from short sellers and journalists alleging the company was built on fraud. In the end, the business quickly crumbled, with Wirecard first admitting that more than $2 billion in cash it had previously reported as merely missing likely never existed, and the company then filed for insolvency a few days later on June 25, 2020.

By that time, Braun, an Austrian who nurtured a cerebral aura with his rimless spectacles, had already been arrested. He has remained in custody for the best part of two years, making only a brief public appearance in Berlin two years ago in November where he was questioned by a parliamentary committee seeking to shed light on the scandal. He provided no insights into what may have led to the breakdown of the erstwhile darling of investors and politicians.

Braun appeared in court on Thursday in the instantly recognizable suit and black turtleneck sweater, following closely as prosecutors read through the more than 80 pages of charges.

Prosecutor Matthias Buehring detailed how Braun, his co-accused and others at Wirecard allegedly set up an elaborate system of fake accounts and payments to make credit providers and investors believe Wirecrad was a thriving business.

“The goal was to inflate the balance sheet and the sales to make the company look financially stronger and dress it up as more attractive for investors and clients,” said Buehring. They wanted “to conceal that the real business of Wirecard was loss-making and the loans sought were needed to prevent its collapse.”

Warning Signs

Wirecard’s demise proved an embarrassment for Germany’s regulatory and political institutions because red flags had existed for years. Damning reports by short sellers like Fraser Perring and a series of articles by the Financial Times questioned management’s accounting of business in Asia and the Middle East, charges the company always denied. Instead, Munich prosecutors initially took the company’s side, going as far as investigating journalists and short sellers instead of Wirecard.

As a result of Wirecard’s collapse, the head of the Bafin financial watchdog, Felix Hufeld, was forced to step down in early 2021.

Prosecutors finalized their probe into Wirecard’s decline and fall in March, having spent almost two years retracing the company’s demise. They have charged Braun alongside two co-defendants — former chief accountant Stephan von Erffa and Oliver Bellenhaus, who ran a Wirecard company in Dubai and who has become a key witness.

According to prosecutors, the trio “invented purportedly extremely profitable businesses, particularly in Asia” to make believe that Wirecard was a successful company. In reality though, underlying assets in Dubai, the Philippines and Singapore didn’t exist and paperwork was forged, according to prosecutors.

Large Payouts

Banks paid out loans of about €1.7 billion euros ($1.8 billion) and two bonds totaling about €1.4 billion, “operating under the mistaken assumption of dealing with a successful, prosperous, properly managed and in any case creditworthy DAX company,” prosecutors wrote in a statement when they filed their indictment.

By reporting fictitious results, the trio manipulated markets, using fabricated numbers to seek loans, say the prosecutors, who have charged the three men with aggravated fraud, market-manipulation and false accounting.

Braun was also charged with breach of trust by making Wirecard pay more than €200 million to an obscure company, a maneuver allegedly orchestrated with his right-hand man at the time, Jan Marsalek, then Wirecard’s chief operating officer. Some of the money was channeled back to the men, according to prosecutors.

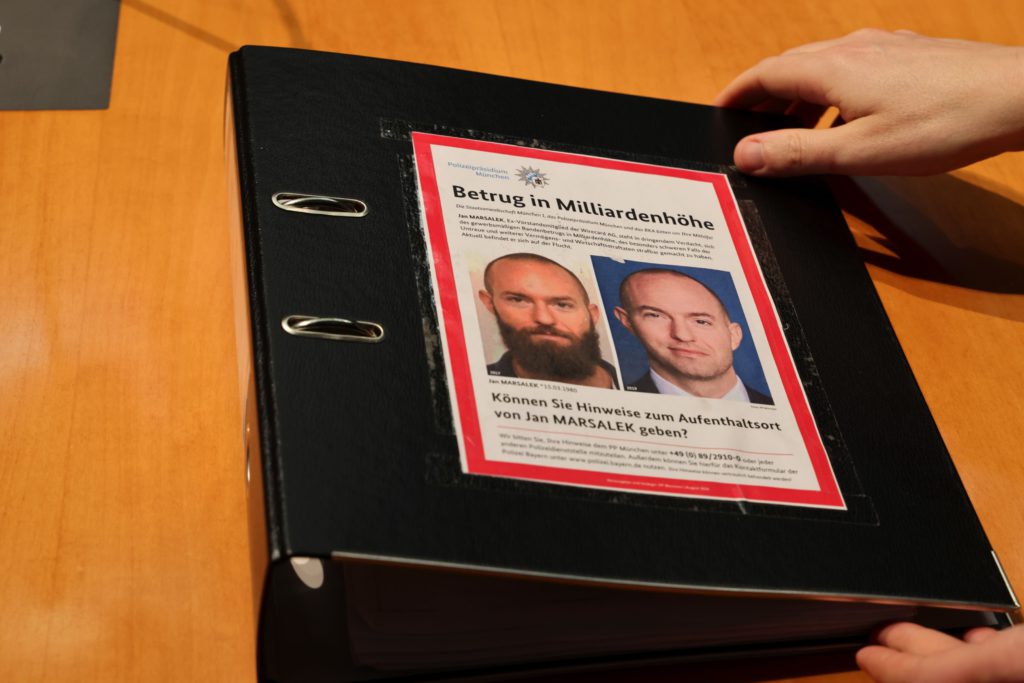

Marsalek fled when the scandal broke and remains at large. He’s now on Interpol’s most wanted list and a Munich probe against him and other suspects continues.

Retracing the business activities took a large team of investigators more than a year, involving more than 40 search warrants in Germany alone and the retrieval of data from places as far flung as Mauritius, the Philippines and Brazil.

No Release

While Germany has had its share of accounting scandals and high-profile corporate collapses, few compare with Wirecard because the failure marked the first time that a company listed on Germany’s benchmark DAX index went bust. Wirecard was long seen as Germany’s ticket to the world of digital payment systems as the world shopped, played and communicated online. When it all turned out to be built of sand, politicians and regulators faced tough questions how a sophisticated economy like Germany could have been so easily tricked, and why nobody followed up on early warnings.

Braun has denied the allegations and has insisted that the foreign partner business at the heart of the fraud allegations was real. His lawyer Alfred Dierlamm has said the evidence suggests that Marsalek and others set up an elaborate system to channel money out of Wirecard and into their own pockets, without Braun’s knowledge.

Dierlamm didn’t reply to an email seeking comment. Sabine Stetter, a lawyer for von Erffa, said she will comment on the case in her opening statement.

But a Munich appeals court that had to rule on several occasions in the past two years whether Braun could be held in pre-trial detention wasn’t swayed by Dierlamm’s argument, finding instead on each occasion that the evidence against the former CEO was strong enough to keep him in custody.

Two Sides

In the upcoming trial, prosecutors will lean heavily on their key witness: Bellenhaus, Wirecard’s former Dubai boss.

A month after Wirecard declared insolvency, Bellenhaus returned to Munich and turned himself in. He was taken into custody and has been held ever since, sharing his inside knowledge in a long series of interviews. He will be instrumental to prove that the partner business was fake, and the trial is likely to provide two contrasting sides: the cooperating Bellenhaus on one side, and the stonewalling Braun on the other.

Bellenhaus’s defense counsel Nicolas Fruehsorger said he expects a lengthy trial given the conflicting defense strategies and testimony of his client’s co-accused.

“But I have faith that the fact-based truth will prevail in the end,” he said.

(Updates with details from courtroom in fifth paragraph.)

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.