Almost as many Britons want higher interest rates to boost their savings income as would rather have an interest-rate cut to keep debt costs under control, according to Bank of England data.

(Bloomberg) — Almost as many Britons want higher interest rates to boost their savings income as would rather have an interest-rate cut to keep debt costs under control, according to Bank of England data.

Of more than 2,100 respondents to a survey by the central bank, 27% said it would be “best for them personally” if rates went up while 30% want them to fall.

The rest said it made no difference, policy should be unchanged or replied “don’t know.”

The results raise questions about how effective the BOE’s monetary policy will be in reining in inflation.

It suggests consumers are less sensitive to interest rate than in decades past and therefore likely to change their behavior more slowly in the face of higher borrowing costs.

“Many households are not as interest rate sensitive as they were,” said Karen Ward, European chief market strategist at JP Morgan Asset Management.

She believes rates may need to rise to between 4.5% and 5% to bear down on inflation, up from 3% currently.

More people now own their homes outright, and are likely to have built up a pot of savings, than have a mortgage.

The household sector is one of the key channels through which rate rises are supposed to restrain demand and bring down inflation.

The data, published last week, was collected after the BOE’s November vote, when the Monetary Policy Committee lifted rates by a historic 75 basis points to 3% to tackle the highest inflation in four decades.

According to the central bank, UK households have roughly £1.8 trillion ($2.2 trillion) of cash savings, which earn more as rates rise, and about £1.5 trillion of mortgage debt.

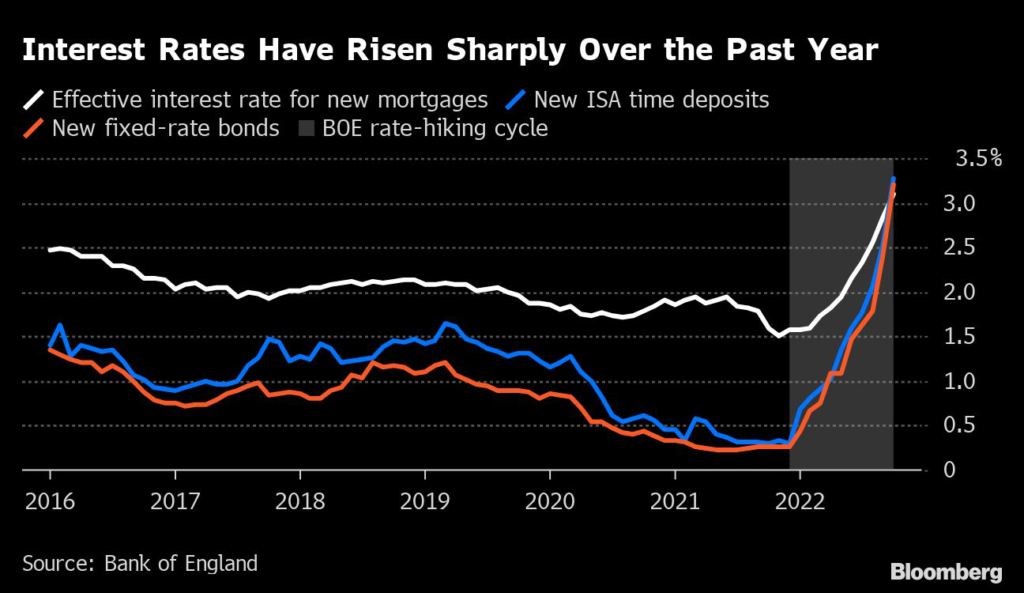

Both fixed-term savings and mortgage rates have risen sharply to over 3% on average in the past year.

Since the start of the pandemic, the survey has consistently found that more households believe higher rates would benefit them personally.

November was the first time the position reversed, suggesting 3% may be a tipping point. The BOE is expected to hike rates to 3.5% on Thursday.

Another reason the link between monetary policy and household spending may have weakened in recent years is the shift to fixed mortgages.

Of the roughly 8 million households with a mortgage, four fifths have tied in for two years or more.

On Tuesday, the BOE said rate rises would affect 4 million of the UK’s 28 million households in 2023 as people came off fixed deals and others remain on floating rates.

About 5 million more households are exposed indirectly as they are in the private rented sector where landlords can put up rents to cover rising mortgage costs.

However, that means two thirds of households are largely unaffected by rate rises through the property channel.

BOE officials have insisted that monetary policy also operates through the financial markets and corporate spending channels.

A breakdown of the BOE data shows those aged 55 and over, who tend to have accumulated net savings, are strongly in favor of rate rises while those between 16 and 44, who tend to have more debt, favor a rate cut.

Those between 45 and 54 lean slightly towards a rate cut.

The “DE” social group, which includes the semi-skilled, the unskilled and the unemployed, is most in favor of higher rates. The BOE data is weighted to reflect UK demographics.

The BOE declined to comment.

–With assistance from Andrew Atkinson.

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.