Smaller sportsbooks like MaximBet and Fubo Gaming have shut down amid mounting industry challenges.

(Bloomberg) — Just a few years ago, the sports-betting industry was flying high. Fresh off a Supreme Court ruling that allowed sports wagering to expand beyond Nevada, one state after another legalized it, investors poured money in and roughly 50 sportsbooks popped up aiming to cash in on the frenzy.

Now, a growing number of the services are shutting down, and the industry’s future looks uncertain.

In a crowded, hyper-competitive landscape dominated by a few deep-pocketed giants, many apps are struggling to survive. Currently, the four biggest sportsbooks — FanDuel, DraftKings, BetMGM and Caesars — control about 90% of the US market, leaving little room for smaller rivals, according to the research firm Eilers & Krejcik Gaming LLC.

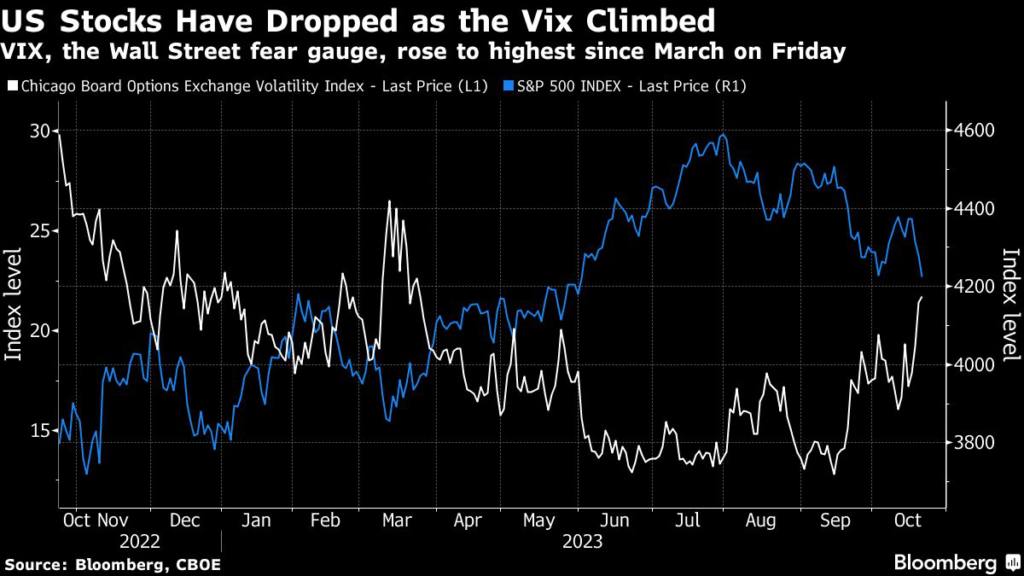

Recently, investors have begun losing patience with apps that hemorrhage money on big advertising campaigns and promotional offers of free bets to attract customers. Since hitting a high in March 2021, DraftKings Inc. has fallen about 80% during a stretch in which the S&P 500 has been flat. The failure to legalize sports betting in California last month has raised questions about how the industry will keep expanding.

“There was this huge, inflated excitement around the space in 2019 and 2020,” said James Kilsby, an industry analyst at Vixio. “In the past 12 months or so the tide has turned.”

Some have already called it quits or scaled back their ambitions. Earlier this year, Churchill Downs Inc., the company that runs the Kentucky Derby, closed its sports gambling operation. Several months later, in October, FuboTV Inc.— a publicly traded streaming service that had expanded into sports betting — did the same. Last month, 888 Holdings Plc, which runs a Sports Illustrated-branded betting app, said it’s shifting its strategy to focus on states that allow online casino games due to “the intense competition in sports betting and the dominance of the top four brands.”

“The market conditions have been brutal during the last 12-18 months.”

The struggles to live up to the initial hype may best be exemplified by the tumultuous saga of MaximBet. In 2020, Carousel Group launched the website SportsBetting.com. A year later, seeking to boost its name recognition, the company teamed up with Maxim, the lickerish men’s magazine known for its scantily-clad models, and rebranded the service as MaximBet.

From the start, MaximBet’s owners pitched their app as a pulse-quickening lifestyle brand, offering giveaways of glittering merchandise and access to glamorous soirees, packed with celebrity guests. In October 2021, MaximBet threw a Halloween party at an air and space museum in Denver where attendees listened to DJs and tested their skills on flight simulators. The rapper Fat Joe performed. One employee recalled handing out snowboards, ski trips, XBoxes and tickets to suites at Colorado Rockies games.

Over time, MaximBet experimented with other strategies to stand out. It tried, unsuccessfully, to persuade Colorado regulators to approve betting on the Puppy Bowl. It struck a marketing deal with Colorado Rockies outfielder Charlie Blackmon, making him the first active baseball player to be paid by a sports betting company in more than a century. And in May, MaximBet announced that Nicki Minaj, the popular rapper with more than 200 million Instagram followers, was becoming an investor, adviser and ambassador for the brand. According to the company’s press release, Minaj would promote MaximBet’s “lifestyle components” and help attract more female bettors. TMZ promptly crowned her the “1st Lady of Sports Betting.”

“Get ready for the sexy parties and remember: scared money don’t make NO MONEY!!!!” Minaj said at the time. “Place your bets!!!!”

But in the months that followed, besides a smattering of social media posts, Minaj did little to promote the app, according to a former employee. Minaj didn’t respond to a request for comment through her publicist. Meanwhile, the allure of Bacchanalian betting bashes failed to produce a stampede of new subscribers.

In its first six months operating in Colorado, MaximBet spent $3.7 million on marketing, or more than double its gross gaming revenue, according to an investor deck viewed by the sports business website Sportico. On Nov. 16, after struggling to find investors, MaximBet announced it was shutting down. According to a person familiar with the matter, in its short, festive life, MaximBet had amassed fewer than 10,000 customers.

Daniel Graetzer, founder of MaximBet, disputed that number. In hindsight, he said he wished he’d started MaximBet two years sooner and raised more money when it was easier to do so.

“The market conditions have been brutal during the last 12-18 months,” Graetzer said in an email.

These days, investors are often more reluctant to fund sports-betting companies, in part, because the decline in DraftKings’ stock price has cooled interest in taking companies public, dimming the prospects of a lucrative exit, said Chris Grove, a partner emeritus at Eilers & Krejcik Gaming and an investor in early-stage sports betting companies.

The rash of sportsbook shutdowns is already leaving a mark on the world of professional sports teams. Last year, Fubo reached a sponsorship deal with the the New York Jets that involved opening an expansive Fubo-branded lounge at MetLife Stadium where fans could place sports-related bets in kiosks or via smartphone. Now, in the wake of Fubo’s exit from the betting industry, the Jets are suing Fubo, alleging the company still owes the team money. A Fubo spokeswoman said the Jets’ complaint “is without merit” and the company plans to “vigorously defend our position.”

The spate of closures likely won’t mean much to giants like FanDuel, which would see little benefit from buying smaller apps with few customers and inferior technology, Grove said. Instead, he expects to see more mergers between sports betting companies and online casinos, which are more profitable. In May, DraftKings bought Golden Nugget Online Gaming Inc., which offers games like online poker.

After four years of intensive lobbying, sports gambling is now legal in more than 30 states. But after California voters rejected legalization last month, “future market expansion is going to be much harder to achieve,” said Kilsby, the analyst at Vixio. The industry’s biggest hope may be persuading Texas to legalize sports betting in next year’s legislative session.

How a potential recession could impact customer activity in the months ahead is unclear. To date, little research has been done on the connection between economic downturns and sports gambling. During the last global recession in 2008, legalized online sports betting did not exist in the US.

Whatever happens economically, more sports-betting apps are expected to shut down. Eilers & Krejcik, the research firm, said last month that Fox Bet, a sports betting app owned by Flutter Entertainment Plc, was on “borrowed time” and “closure looks inevitable.” Three years after its debut, and with heavy promotion during Fox’s TV broadcasts, the app has so far captured less than 1% of the US market. Flutter declined to comment.

“We’re starting to get a sense of who the winners and losers are,” Grove said.

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.