When Epameinondas Gerolimatos, a soft-spoken 41-year-old, got his degree in economics in 2003, he assumed, like many other Greeks, that a career in banking would mean long-term job security.

The 2010 financial crisis and its decade-long fallout rattled his country’s faith in the industry, but Gerolimatos is again part of a sector that is shaping up to become one of Greece’s most influential – tech.

(Bloomberg) — When Epameinondas Gerolimatos, a soft-spoken 41-year-old, got his degree in economics in 2003, he assumed, like many other Greeks, that a career in banking would mean long-term job security.

The 2010 financial crisis and its decade-long fallout rattled his country’s faith in the industry, but Gerolimatos is again part of a sector that is shaping up to become one of Greece’s most influential – tech.

After signing up for a national unemployment registry, in May Gerolimatos was offered a spot in a free certificate program run by Microsoft.

A month later, he was one of 25 out of 150 to pass his course, which is part of an effort to train 100,000 would-be specialists in information technology by the end of 2025. Three months and yet another Microsoft certificate program later, Gerolimatos was weighing job offers, eventually becoming a security engineer at a global accounting firm.

As tech companies go big on Greece, Gerolimatos’s story may soon become common.

While a recent surge in inflation and a growing fear of recession could slow international investment, so far, the sector has been thriving.

In 2020, Microsoft announced plans to build three data centers outside Athens, doubling its number of local employees to just above 300 for the time being.

In Thessaloniki, the country’s second-largest city, Cisco set up an international innovation and digital skills development center, and Pfizer is building a network of research hubs focused on artificial intelligence.

This fall, Google announced that it would break ground on a cloud hub near Athens that it claims will boost the country’s economic output by more than 2 billion euros ($2.1 billion) and create 19,400 new jobs by 2030.

The government has also been pouring money into the sector: in coming years, it plans to develop innovation districts in Athens and Thessaloniki that will house large enterprises, academic institutions, startups and incubators.

Beyond the Mediterranean nation’s obvious charms and easy access to Africa and the Middle East, global tech players have also been lured by generous tax incentives and an abundance of renewable solar and wind energy.

Although the numbers remain relatively low – just above 330 million euros in 2021 – foreign direct investment in Greece’s information and communication technology sector has more than tripled in the past two years, and now accounts for roughly 3% of the country’s total GDP.

In 2021, the sector ranked sixth out of 19 economic sectors in terms of attractiveness for foreign direct investment. If the ruling New Democracy party has its way, that number could grow bigger still.

In a recent speech at the opening of a new data center run by cloud computing company Digital Realty, Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis announced his ambition for technology to contribute 10% to the country’s economic output in the next five years.

“This year, Greece set a record in filing and granting approvals for new patents,” the Prime Minister told the crowd, citing this as evidence of ongoing innovation.

Since taking office in 2019, when the country was starting to climb out of its debt crisis, Mitsotakis has pushed tech as one of Greece’s paths toward prosperity.

This is an appealing narrative, and a slightly ironic one for a prime minister in the midst of a tech-related scandal.

Mitsotakis has been under intense pressure since August, when it was revealed that businesspeople, journalists and political opponents had their phones tapped with sophisticated malware. The government has repeatedly denied that its security services bought or used the spyware, called Predator, whose parent company was based in Greece.

Still, action has been taken to rein in renegade tech use. In early December, the lawmakers approved a law that would ban malware and make it harder for national intelligence services to put someone under surveillance.

Mitsotakis, naturally, wants to direct public attention elsewhere.

With a national election scheduled for next year, he has been trying to make good on previous campaign promises, such as making it easier for people who left the country during the economic crisis to return home.

A rise in well-paid tech jobs has offered a critical assist in achieving this goal.

“Some 20% of new hires are people who were living and working abroad,” said Theodosis Michalopoulos, Microsoft’s general manager for Greece, Cyprus and Malta.

One returnee is Christina Leimoni, who left a director-level job in the UK to become Microsoft’s Chief Operating Officer for Greece, Cyprus and Malta.

Before she took the position, Leimoni hadn’t considered moving back to her home country, in part because she was concerned that as a lesbian, she and her wife and daughter “would not have been regarded as a family.” The dynamism of today’s Greece convinced her to take the role, and rather than return to the closet, Leimoni has become an advocate for LGBTQ issues.

“There’s an amazing momentum in the country,” she reflected.

The c-suite isn’t the only rank at which the demand for experience has outpaced available supply. To draw in skilled international talent, the government launched a visa program in 2021 for digital nomads, and so far has issued some 450 visas.

For local talent, tech companies have taken it upon themselves to train prospective employees. In addition to Microsoft’s certificate programs, more than 250,000 businesses and individuals have gone through Google training initiatives in Greece.

“Technology can’t be useful if there are no digital skills,” said Peggy Antonakou, the company’s Southeast Europe general manager.

Of course, Athens is far from the only city with aspirations of becoming a tech hub.

Lisbon has tried for years, with limited success. But with Greece now on stable political and economic footing, big tech companies say that investing in it isn’t a difficult decision. The country has sped up its digital transformation in recent years, boasts a well-educated population whose salary expectations are a relative bargain for international employers, and is renowned for its stunning natural beauty and quality of life.

As Antonakou said of the search giant’s investment, “If not now, then when?”

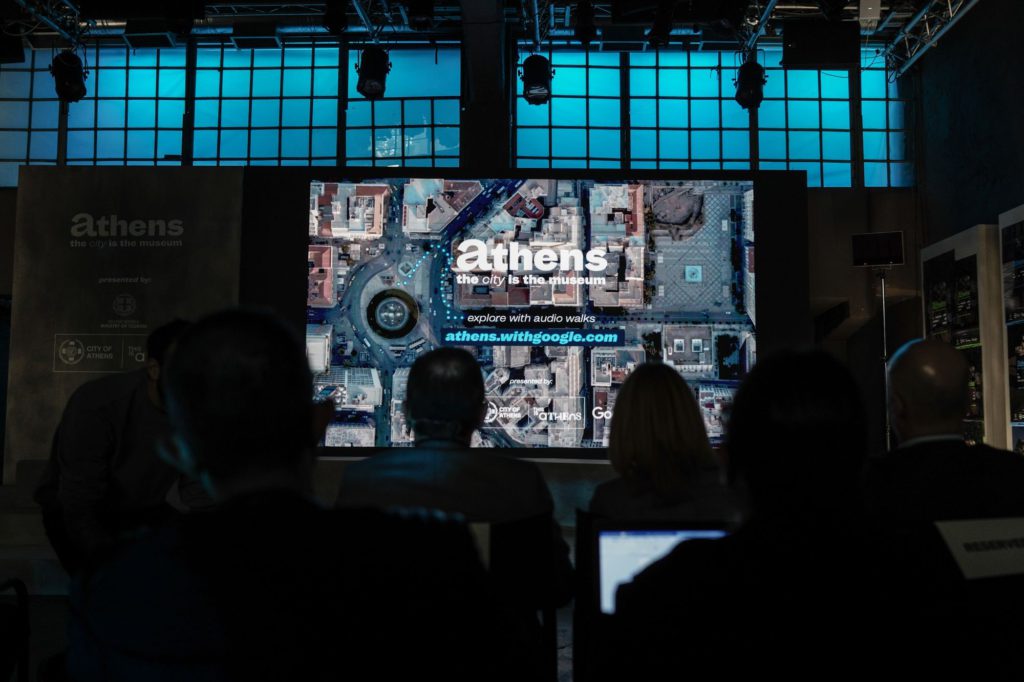

On a warm and sunny November morning in Athens, a mix of journalists, laid-back locals and government officials gathered at a café and events space close to the site of an ancient market for the launch of a new website that was the result of a collaboration between Google, the tourism ministry and the city.

As attendees stretched out on blue banquettes bearing the logo of Olympic Airlines, presenters explained how the site’s curated audio walks offered a novel take on Athens by featuring stories from native Athenians.

The aim, they said, was to transform the Greek capital into “an open-air museum.”

Athens, of course, has long been described as a museum. But the infusion of tech money and jobs promise something different, for both the capital and country at large.

Rather than looking backward, the hope is that Greeks may soon have another success story to brighten their future.

(Updates with further details on FDI in fifth paragraph. A previous version of this story was corrected as it described “Athens: The city is the museum” as an app.

It is a website.)

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.