Federal scrutiny over startup’s prescriptions stirs discussion about venture capitalists’ role in funding behavior telehealth firms

(Bloomberg) — A few months into the Covid-19 pandemic, as lockdowns were boosting demand for telehealth and venture capitalists were looking for the next big idea in that field, one startup pitched a chance to take advantage of a “once-in-a-lifetime sea change” in psychiatric care.

In a July 2020 pitch document, Cerebral Inc. cited a federal rule that was loosened amid the pandemic to allow telehealth clinicians to write prescriptions for controlled substances such as the stimulant Adderall. This new freedom to prescribe highly regulated drugs online, along with Cerebral’s medication-management service, therapy offerings and a planned app, would accelerate a “landgrab” and boost its revenue to $65 million from $6 million in 18 months, according to the pitch.

The document offers a rare look at how the company attracted investors with projections of rapid growth as Cerebral competed with rivals to take advantage of the telehealth opportunity. Much of its plan was rooted in prescribing drugs that carry risk of abuse and in a high-volume approach that former employees say meant short appointments and infrequent followups.

“Now is the time to capture growth and establish [a] brand synonymous with telemental health,” the pitch says. And for almost two years, that’s exactly what happened. Led by founder Kyle Robertson, Cerebral saw rapid growth and three successful fundraising rounds that rocketed its valuation to $4.8 billion by December 2021. Then the company experienced a sea change of its own.

Bloomberg Businessweek reported in March that some Cerebral clinicians said they felt pressured to prescribe certain controlled substances. Two months later, US prosecutors told Cerebral that it was a subject of a federal grand jury investigation into possible “violations of the Controlled Substances Act.” Executives have denied any wrongdoing, but they announced in May that Cerebral would stop prescribing most controlled medications. The company’s board ousted Robertson from the chief executive officer’s role. And in July, executives disclosed that they had repriced Cerebral’s closely held shares to reflect a 95% drop in valuation from the peak. DEA agents have also interviewed employees of another telehealth company, Done Global Inc., asking about prescription practices, according to people familiar with the matter. Done didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Read more: ADHD Drugs Are Convenient to Get Online. Maybe Too Convenient

Now, in hindsight, the federal scrutiny has stirred public discussion among venture firms about how much responsibility investors bear when they encourage young companies to grow rapidly, especially in the digital health sector.

Robertson has alleged that the company’s “rapid and aggressive expansion of its controlled substance prescription practices” was the result of pressure from major investors — a claim that current executives have disputed. The former CEO made the allegation in a letter last month that demanded access to Cerebral’s corporate books and records. Robertson, who identifies as gay, also wrote that he experienced anti-LGBTQ bias from fellow members of the company’s board.

“These claims against Cerebral and its board are categorically untrue and baseless in law and in fact,” the company said in a prepared response. “They run contrary to our culture of championing diversity and inclusion and are the antithesis of what we stand for as a company. We will defend ourselves vigorously against these meritless and opportunistic claims.” One of the company’s biggest investors, SoftBank, also dismissed Robertson’s allegations, calling them “meritless.”

Many of the venture fund executives who passed on Cerebral said they saw warning signs — including plans to capitalize on the relaxed prescription rule — in some of its earliest business plans, including the July 2020 pitch deck. That document spells out how the young company planned to use initial funding to launch a therapy offering and introduce tiered subscriptions for varying service levels and price points, among other things. The startup’s competitive advantage would be its “Uber-like network effects and economies of scale,” part of a “one-stop solution for mental health” that would become cheaper and generate higher profit margins as more people signed up, according to the presentation. By the end of 2020, the pitch deck says, the company would introduce treatment for Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, which is usually treated with controlled stimulants.

Representatives of more than a dozen investment firms told Bloomberg News that after hearing Cerebral’s early pitches, they questioned whether the startup had too many incentives aimed at boosting growth rather than delivering high-quality care, as one executive put it.

“It was a volume business that was all about how many customers can I attract in a short amount of time,” said Dan Gebremedhin, a partner at Flare Capital, a venture capital firm that invests in early-stage healthcare startups but passed on Cerebral during the Series A funding round. “Just because I can see 30 patients in a day, doesn’t mean I should.” He added that Cerebral’s mission to increase access at a lower cost was noble, but treating more serious conditions conflicted with how it made money. “At the time, the company was focused on treating depression and anxiety,” he said. “But Adderall and stimulants? That’s a different story.”

In response to specific questions about its pitch deck and presentations to investors, Cerebral sent a prepared statement: “Delivering high-quality care for our patients is Cerebral’s highest priority and the company has made a significant commitment to clinical quality through a combination of rigorous training, data-driven insights, and investments in advanced technology.”

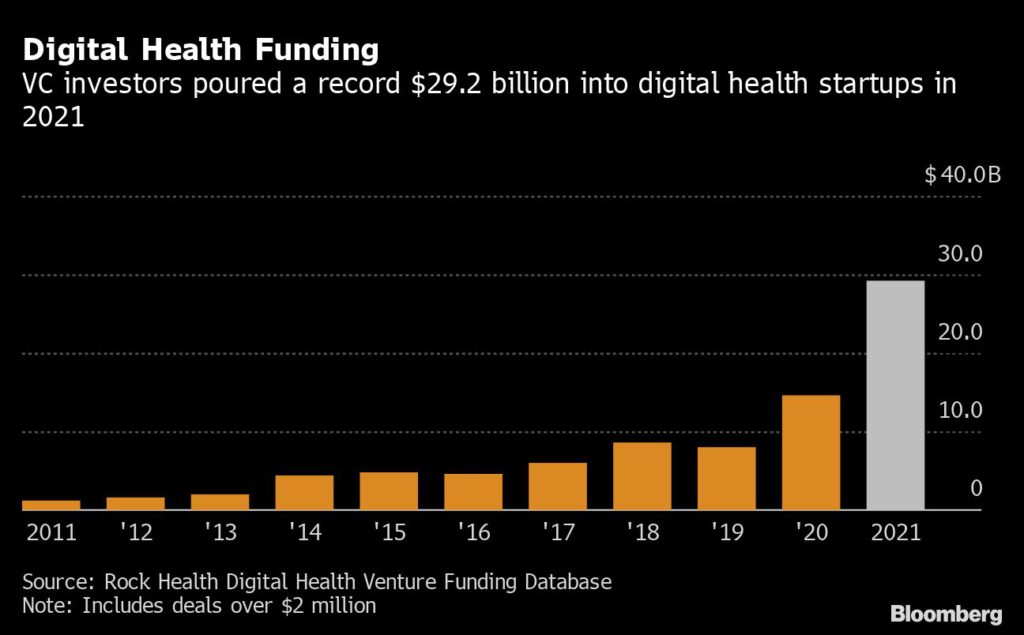

Telemedicine firms such as Cerebral aim for a lower-cost, wider-access approach that experts say has the potential to disrupt a healthcare system widely recognized as dysfunctional in many respects. After the pandemic hit, a record amount of investment cash flooded into the sector, and competition to fund the best ideas went into overdrive.

The scrutiny surrounding Cerebral and telehealth ought to serve as a lesson for venture capital executives, said Deena Shakir, a partner at Lux Capital.

“Hopefully, it puts pressure on VCs to do additional diligence before making an investment,” said Shakir, whose firm passed on a chance to back Cerebral. She cited the importance of examining corporate governance plans and board responsibilities closely but added that mental healthcare needs additional funders’ attention. “I hope it does not dissuade investors from investing seriously in mental health innovation, as there continues to be a massive need and opportunity for impact.”

Aike Ho, a partner at the early-stage venture firm ACME Capital, condemned what she called a “growth-at-all costs” ethos in Silicon Valley during a panel discussion at a digital health conference in June. “Who knew the next drug cartel would be VC-backed?” she said, without citing any company by name.

Similar concerns were aired last month when investors and executives from pharmaceutical and insurance companies gathered for an event at the HLTH Conference called “Scaling Mental Health, But Not at All Costs.” Liam Donohue, a founding partner at .406 Ventures, said first-time health investors must have patience and understand that mental health startups can take longer to generate revenue than other technology companies. Much of the capital that poured into mental health in the pandemic era “was from funds that don’t live in health care and don’t understand the ecosystem,” he said. “I sit on the board with a few and when you tell them that 18 months is a short sale cycle for a payer, their heads explode.”

Almost half the $29 billion of investment that digital health attracted in 2021 came from VCs who’d never backed healthcare companies before, according to a report from Rock Health, a consultancy and venture firm. As record numbers of startups held multiple fundraising rounds, the average digital health deal in 2021 brought in $39.5 million, up 82% from 2018, according to Rock Health’s data.

Most of Cerebral’s early backers were small VC firms with little experience in digital health. However, one major healthcare investor, Oak HC/FT, got involved, leading the firm’s first fundraising round, which brought in $35 million in October 2020. Its involvement lent credibility to Cerebral, other investors said. Oak HC/FT didn’t respond to requests for comment for this story.

A second funding round eight months later in June 2021 took the company’s valuation to $1.2 billion as it collected $127 million from prominent investors such as Len Blavatnik’s Access Industries, Silver Lake Waterman and Bill Ackman. Oak HC/FT reupped its initial investment with a second check. By then, Cerebral had begun offering ADHD treatment and said it would use new capital to add treatment for more complicated conditions, such as bipolar disorder, substance abuse and eating disorders. Silver Lake Waterman didn’t respond to requests for comment for this story. Representatives for Ackman and Access declined to comment.

Cerebral’s fundraising came as the Covid pandemic ignited fresh investor excitement over digital health firms.

“It was a total FOMO ecosystem,” said Angela Lee, a professor who teaches venture capital and leadership at Columbia Business School. “One way to compete is by being quicker with decisions, so investors weren’t asking too many questions.” She cited a January analysis by DocSend, a secure document-sharing platform, which showed that, on average, VCs spent just two minutes and 28 seconds reviewing pitch decks from all types of companies in the fourth quarter of 2021 — less time than in any previous quarter since DocSend started tracking the data in 2018.

Cerebral’s investors, meanwhile, have seen the firm’s valuation drop; its shares, which had reached $153 at their height roughly a year ago, have plummeted as much as 70% in some private stock exchanges, according to people familiar with the matter. According to a public filing with the California Office of Financial Technology Innovation, the company repriced its stock down to $1.39 per share in July, reflecting a 95% drop in its valuation compared with its peak last year.

Two Cerebral seed investors who asked not to be identified because of confidentiality agreements said they want to cut ties to the company. WestCap Group, which participated in all three of Cerebral’s fundraising rounds, is considering selling some shares, according to people familiar with the matter. “We are not marketing and have never marketed our shares,” a spokeswoman for WestCap said in a statement. She said the firm received “one inbound” offer and declined.

For Oak HC/FT, Cerebral’s setbacks contrasted with some previous successes. The fund had backed a number of digital health darlings, including Maven Clinic, Brightline Health and Noom. Speaking on a January 2022 webcast presented by law firm Cooley LLP about investment trends in digital health, Oak HC/FT partner Bill Deitch described the types of startups that catch his eye, without mentioning Cerebral specifically. It’s not always the case that winners boast glowing economic indicators right away, he said, “but they’ve got the early proof points that there’s lightning in the bottle.”

Since then, Oak HC/FT has removed mentions of Cerebral from its website.

–With assistance from Polly Mosendz.

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.