The data are so important, staff were once instructed to have no facial expressions when walking the reports into the West Wing of the White House.

(Bloomberg) — The data are so important, staff were once instructed to have no facial expressions when walking the reports into the West Wing of the White House.

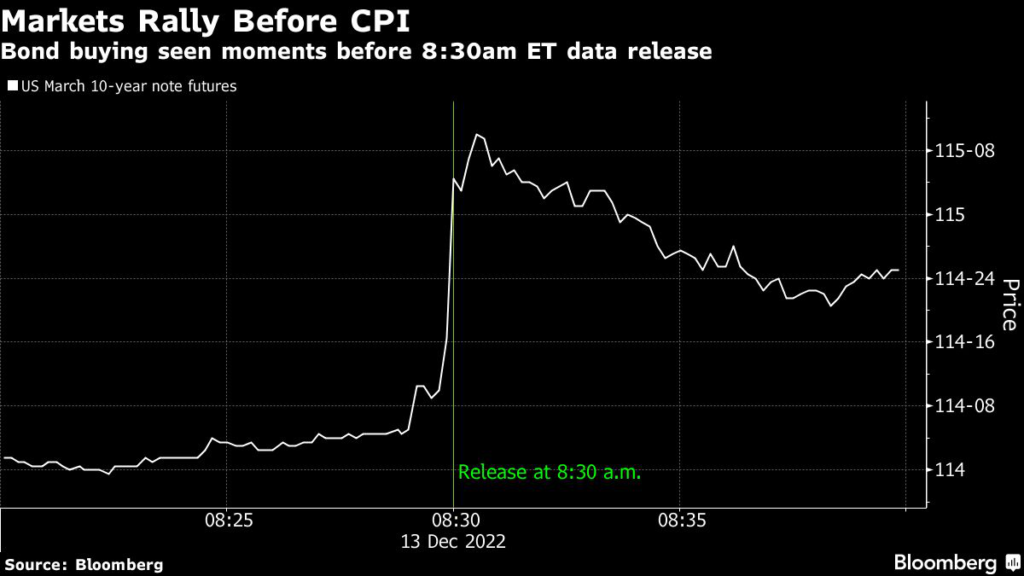

And yet, a surge in trading last week in the minutes before the release of the consumer price index — a closely watched US inflation measure — spurred concerns the figures fell into the wrong hands.

Those who develop, handle, and publish highly sensitive government data like the monthly CPI follow strict protocols.

Government officials said there was nothing different this time about the process, and no evidence of a leak or a hack.

Still, there are lingering questions, including whether someone could have pulled the November data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics website before its official publication at 8:30 a.m.

Eastern time. The BLS declined to discuss its release procedures, citing security reasons.

As inflation jumped this year to a four-decade high, the CPI has become one of the most watched economic indicators and a key data point in the Federal Reserve’s decisions to raise interest rates aggressively.

In the lead-up to the Dec.

13 release, an unusual volume of buying took place in Treasury futures. The rally continued after the data came out below estimates — meaning inflation was cooling faster than expected — delivering profitable trades for those who bought just before 8:30 a.m.

In a statement, the Securities and Exchange Commission declined to comment “on the existence or non-existence of a possible investigation.” A Commodity Futures Trading Commission representative also declined to comment.

Both regulators could have authority to investigate any potential attempts to manipulate the Treasuries market.

Here’s a timeline of what happens behind the scenes in the days before the CPI is released.

The account is based on comments from present and former employees across the BLS, the Treasury Department, the Fed and the White House Council of Economic Advisers, an agency that provides the president with economic advice.

A Week Before CPI

A small group of BLS staff begins compiling the CPI report about a week before its publication.

Once the report is drafted, it is reviewed by Robert Cage, assistant commissioner for consumer prices and price indexes, and Jeffrey Hill, associate commissioner for prices and living conditions.

BLS Commissioner William Beach also reviews the report, typically two days before its release to the public.

“It’s highly orchestrated and tightly controlled,” said Erica Groshen, a former BLS commissioner.

“This is a well-oiled machine.”

Eve of Report

Around 2:30 p.m. or 3 p.m. the day before publication, BLS sends the figures to the Council of Economic Advisers via secure electronic transfer, according to Karen Ransom, division chief of the division of publishing services at BLS.

At 4 p.m., BLS officials give a presentation to the CEA in a virtual meeting via Microsoft Teams.

The CEA then shares this information with a few key figures across the White House, Treasury and Fed, including Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen and Fed Chair Jerome Powell.

The CEA also briefs the director of the President’s National Economic Council – Brian Deese – and President Joe Biden via memo.

A limited number of CEA staff and an even smaller number of senior-most administration officials receive the reports on a strictly need-to-know basis, said a White House spokesperson.

The White House is not aware of any leaks, and there are very strict security protocols to prevent them, the person said.

When CEA staff walked the material over to the West Wing of the White House from their quarters at the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, about a two-minute walk, they would place it in a manila envelope and then inside a folder or two to make sure nothing was visible, said DJ Nordquist, former CEA chief of staff during the Trump administration.

“We were so worried that reporters knew it was a data day — and there were always reporters hanging around that area — that we would make sure to double or triple wrap the papers and walk across the street looking very serious.

No facial expressions,” said Nordquist, who is now executive vice president at the Economic Innovation Group, a think tank. “That’s literally how paranoid we were.”

The report is sent to the Treasury and Fed via encrypted, secure transmission and a secure network.

A Treasury spokesperson said the information is delivered to a secure facility and provided to a limited number of individuals who are permitted access.

The Fed declined to offer any details, but Eric Kollig, a spokesperson, said the central bank “has rigorous safeguards in place for handling non-public and market-sensitive information.”

The same goes for BLS.

Ahead of big indicators, access to the office areas where the report was being prepared were highly restricted, said Groshen, who served as commissioner from 2013 to 2017.

“Even the garbage cans are not emptied by the maintenance staff during that time,” she said.

CPI Morning

The morning of the release, a small group of staff at the Labor Department’s Office of the Secretary is given a virtual briefing starting at 8 a.m., Ransom said, adding that who attends depends on availability.

Everyone with early access is unable to leave the meeting until the report is out and bound by a nondisclosure agreement to keep the data secure.

Before the pandemic, a group of reporters received the data the morning of the release in a secure “lock-up” room at the US Labor Department.

Those lockups were disbanded during the 2020 shutdowns and haven’t been reinstated, part of an initiative to further ensure equal access to the data. Like other news outlets, Bloomberg News gets reports like CPI when BLS releases them to the public.

BLS declined to further elaborate on how the report is published online, saying that “for security reasons we do not discuss the details of our release publication procedures.” Last week, the agency said there was “no evidence” that its information-technology systems “were in any way compromised” and that no suspicious activity was detected.

Officials must also follow strict policies put in place by the White House Office of Management and Budget to “prevent early access to information that may affect financial and commodity markets.”

“Trust is very important for the statistical agency to be able to achieve its mission,” said Groshen, the former BLS commissioner.

“It is up to the agencies to show that they are worthy of that trust — to be transparent about their methods and to take the steps that they need to protect the data.”

“They have done an amazing job despite being underfunded for a very long time,” she said.

–With assistance from Edward Bolingbroke, Craig Torres and Ben Bain.

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.