Don’t blame bad liquidity for every ill in a year of central bank-spurred market fireworks.

(Bloomberg) — In the telling of investors lashed by soaring interest rates and runaway inflation, Wall Street trading went from bad to worse this year — all thanks to vanishing liquidity. Stock and bond markets are now supposedly so broken that money managers were unable to buy and sell in size without moving prices along the way, making the great 2022 selloff even worse.

Cue violent swings in everything from Treasuries and small-cap equities to commodities.

Yet casting liquidity as enemy No. 1 is an all-too-familiar ritual whenever markets go south, especially in a year of chaos that’s been the worst for 60/40 portfolios since the global financial crisis.

In the view of top traders from the likes of Man Group, BNP Paribas Asset Management and DWS Group, tough investing conditions are par for the course as central bankers drain financial excess from every corner, stoking volatility and liquidations.

That’s not to say the plumbing in key markets isn’t in need of fixing, especially within fixed income, whether it’s US Treasuries, European repurchase agreements or UK gilts. But senior traders canvassed by Bloomberg say blaming the middlemen for every ill over the past 12 months is simplistic — and global markets are far from busted at their core.

“There isn’t anything systemically wrong in the markets and I don’t think we have any existential threat,” says Rupert Fennelly, head of EMEA electronic equities sales and coverage at Barclays Plc. “Things will get better when the macro backdrop gets better.”

Institutional pros are instead grappling with more esoteric liquidity challenges in their day-to-day. Among other issues, the stock market is getting crowded at the closing bell as index-tracking funds rebalance en masse. Meanwhile, retail trading is largely benefiting firms such as Citadel Securities rather than public exchanges, spurring US regulators to propose reforms to the market structure that they say would boost transparency and competition.

Here’s a rundown of the big liquidity debate across assets, according to executives who spend their day on trading floors.

First off, yes, bond trading has proved challenging this year

Bid-ask spreads on US Treasuries famously widened in the great 2022 bond bear market, but research from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York suggests they still remained below pandemic highs. By other measures, things proved more problematic. A gauge of how much Treasury yields are deviating from a fair-value model jumped near the highest since 2010.

Even Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen expressed concerns over bond liquidity. New York Fed researchers pointed out last month that market depth weakened in the two-year note akin to the dark days of the pandemic, reflecting uncertainty over the near-term outlook for monetary policy.

One well-known reason: Tighter post-2008 regulations have spurred banks to take less bonds on their balance sheet to facilitate trading. Meanwhile, high-frequency firms can’t sharply expand capacity in times of stress, says Darrell Duffie, a professor at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, who has worked with the Fed to study market liquidity.

At the same time, the Treasury market as a percentage of the US economy is now significantly larger than before the global financial crisis, while the central bank is no longer backstopping private-sector buyers as it pares its bloated balance sheet.

“It means that the market has to handle more Treasuries with the same amount of intermediation capacity. That makes it more difficult for the market to absorb that,” said Duffie. “So it doesn’t take as big of a stress event to cause a destruction to liquidity or even a market dysfunction.”

However, the Fed research also suggests that poor liquidity in the five- and 10-year note is broadly in line with the overall volatility of the market and trading volumes have held up. Other market participants say things are at least beginning to improve, especially in light of the fact that the bond selloff has eased of late.

“Anything that is rate-sensitive has been pretty challenging to trade,” said Chris Woolley, director of trading at Man Group, which runs about $138 billion. “If you look at top-of-book liquidity in bond futures for example, that is probably at its most recent lows, but I think the momentum of that has slowed down in terms of getting worse.”

The market is at least offering solutions to the bond-liquidity problem

With banks taking on less risk, fixed-income investors are increasingly trading with each other in an arrangement that may eventually give rise to all-to-all trading, with platforms that give a broad array of participants the ability to transact on a level playing field.

“Broker-dealers are acting more like agents and matching buyers and sellers,” says Doug Longo, co-head of product specialists at Dimensional Fund Advisors, which runs $540 billion. “Because of that we’ve moved a significant amount of trading to peer-to-peer networks.”

Another hot trend is portfolio trading, where investors get to buy or sell a large slate of bonds in one go, partly thanks to the boom in fixed-income exchange-traded funds.

“You don’t execute bond trades line by line anymore,” said Werner Eppacher, global head of trading at DWS Group, which manages roughly $886 billion. “That’s clearly an improvement, especially for institutional investors.”

All told, the bond marketplace has all the ingredients to imitate the more-liquid stock market, with electronic trading of corporate securities notching a record in 2022, according to Coalition Greenwich.

“If you look at the average daily trading volume, it’s pretty much in line in terms of where it was in 2021,” said Longo. “When asset managers design a strategy that doesn’t work in all environments, the first thing they start to complain about is there’s no liquidity in the market.”

Stock liquidity has by no means reached crisis levels, even if this year was a little tough

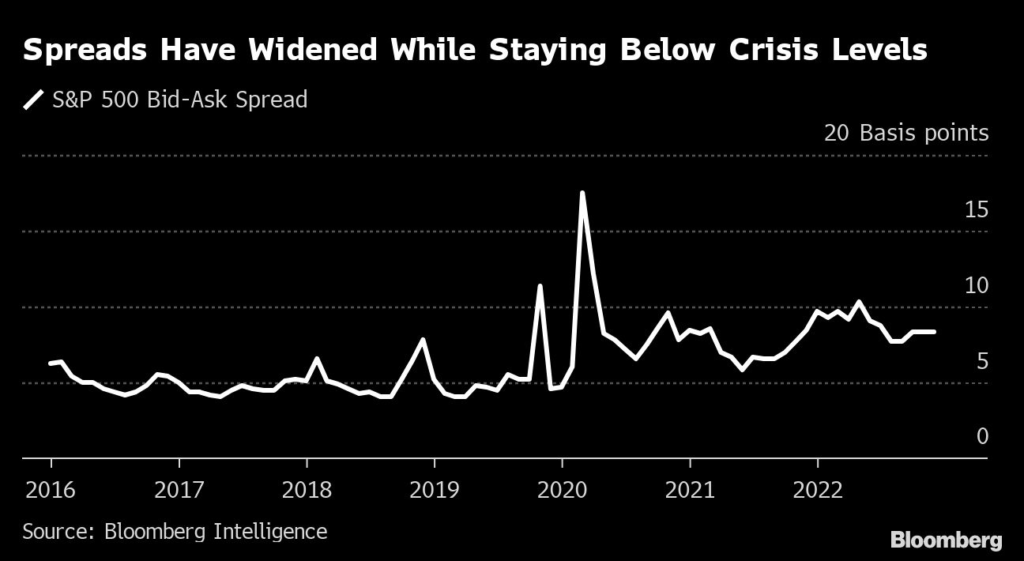

Bid-ask spreads on the S&P 500 Index are nowhere near the levels notched during the 2020 selloff, though they have yet to recover to pre-pandemic levels. That’s one reason why stock traders interviewed by Bloomberg are surprisingly sanguine.

“I actually don’t think this year has been particularly worse than other sell-off markets,” said Inés de Trémiolles, global head of trading at BNP Paribas Asset Management, which oversees about $612 billion. “I’m old enough to remember other turbulent market times when there was a sudden regime change. In this case we knew monetary policy was going to change at some point.”

That’s not to say things are going swimmingly given still-elevated transaction costs across securities. Yet it’s hard to find evidence of big structural problems, according to Hitesh Mittal, the former head of trading at quant firm AQR Capital Management who now runs the algo shop BestEx Research. He says equity spreads this year are still adhering to their usual relationship with volatility, a sign that markets are by no means broken at their core.

“Liquidity is poorer in the market, but it is supposed to be poorer when volatility is higher,” said Mittal.

A more pressing concern perhaps: Trading volumes are increasingly concentrated around the close

A flurry of rules-based rebalancing and hedging is increasingly taking place toward the close of a stock session as index managers track closing prices, quants obey volatility targets and market-makers hedge their exposures. All that late-session activity is spurring fears that the equity market is more vulnerable to volatility blow-ups.

According to de Trémiolles at BNP, it’s increasingly a similar story in other asset classes like bonds, currencies and futures thanks to the rise of passive investing.

“We have people who have a lot less activity during their day and then all hands need to be on deck around the close,” she said. “I pray that we don’t have any type of operational incident — you know an electricity blackout or whatever — around that time.”

In Europe, as much as 24% of monthly on-venue stock volumes were executed at the closing auction in 2022, compared with typically less than 20% in the years before 2018, according to data provider big xyt. Similar dynamics are on display in the US. This has fueled something of a feedback loop, drawing even more funds to trade at the close on the basis that transaction costs may well be lower. Yet this is not an ideal setup for funds that need to trade throughout the session.

“We certainly need to be more thoughtful about how to make sure the funds can get access to the right liquidity at the right points in the day,” said Woolley at Man Group.

Institutional investors are feeling the FOMO when it comes to the retail boom

In the GameStop Corp. era, retail flows at brokerages like Robinhood Markets Inc. are typically handled by a small group of market makers such as Citadel Securities, which often offer a payment in return. These firms mostly execute these trades internally, meaning the orders never end up on open venues like the Nasdaq that display price quotes to the public. As such, individual investors aren’t necessarily contributing to the overall liquidity of the market, given a large amount of stock dealing is effectively conducted in private.

While retail speculation has faded somewhat, an average 42% of stock trading volumes were executed off-exchange this year, compared with 37% in the five years through 2019, data compiled by Bloomberg show. All this is raising questions about whether there’s enough competition for these orders among market makers. It’s something the Securities and Exchange Commission appears worried about. The regulator laid out proposals this month that aim to direct more business to exchanges, while stopping short of banning so-called payment-for-order-flow.

“This is causing challenges for institutional managers like us, when we’re trying to estimate accessible market volume,” said Joel Feinberg, head of trading at Acadian Asset Management, an $83 billion quant firm. “You just see traders in general and institutions tending to move to more schedule-based strategies which split orders up into smaller increments over the course of the day. That leads to more blocks being automated and being traded smaller in size throughout the day.”

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.