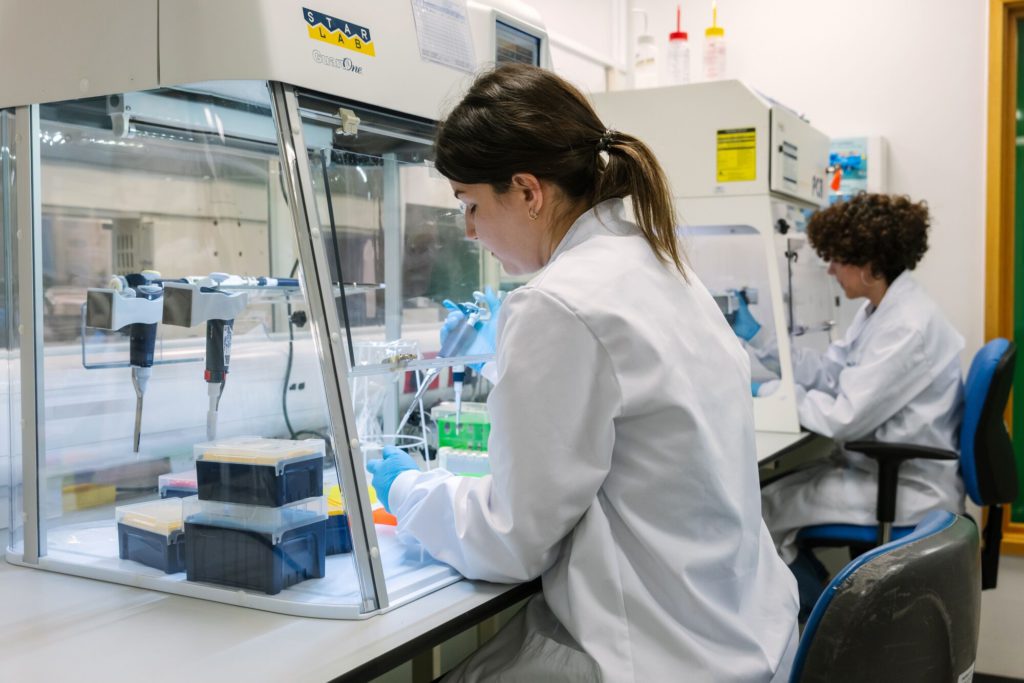

World-renowned academic institutions and a national health care system are a big draw for biotech and life sciences industries.

(Bloomberg) — This is the season when the UK pitches itself as a technology trendsetter.

In November, the government plans to convene hundreds of international financiers and executives to promote investing opportunities in British companies, including those working on nuclear fusion and “deep tech.” That same month, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak will host the inaugural AI Safety Summit, an event designed to position the nation as a global leader on the critical technology.

It’s a tough sell.

A sluggish national economy, tepid capital markets and the lingering impacts of Brexit have left the UK with few tech companies that credibly compete on a global scale. For the upcoming artificial intelligence summit, Sunak is chiefly inviting executives from Silicon Valley.

Still, there’s one area where the UK has the potential to make a big impact.

Several startups working in scientific fields like drug discovery, genomics and medical devices have leveraged Britain’s world-renowned universities and national health-care service to deliver impressive technical leaps — and some commercial success. The Bloomberg Technology Summit, held on Tuesday in London, will showcase a few of these biotech and health care standouts during a series of discussions about the UK’s global role in the most pressing questions in technology today.

“The UK is a very attractive place for the life sciences,” said Simon Dingemans, a senior adviser with the Carlyle Group and the former chief financial officer at GSK Plc.

He cited the concentration of research institutions, government support, and a range of investing vehicles. “That’s why the sector is so alive,” he said.

Last year, Dingemans became chairman of Genomics Plc, an Oxford-based biotech firm that analyzes a person’s genetic risk for disease.

Genomics has contracts with several pharmaceutical and insurance companies, including MassMutual, and reached “substantial revenue” this year for the first time, according to Chief Executive Officer Peter Donnelly.

He said his company, which has raised $82 million, is preparing another funding round.

Tech startup financing is falling in the UK, like everywhere else. Venture capitalists invested £7.9 billion ($9.6 billion) in the country during the first half of this year, a 58% drop from 2022 and below totals in the US and Europe, according to a recent report from data firm PitchBook.

But recent investment into UK health-care services and devices has shown the “most resilience” compared with other sectors, according to PitchBook. A 2021 report from McKinsey shows that the UK has far more biotech startups, venture capital deals and initial public offerings in biotech than the rest of Europe.

The UK leads the world in publications in the field, relative to gross domestic product, according to the study.

For entrepreneurs, the UK’s academic hubs are key for attracting ongoing investing and scientific talent.

“It’s probably the best place to be,” said Tim Guilliams, a biochemist whose drug discovery startup, Healx Ltd. emerged from Cambridge University. One of its chief rivals is Isomorphic Labs, a spin-off of Google’s DeepMind — which itself also came out of a British university.

Less internationally well-known schools are seeding startups as well.

Cerca Magnetics, a company that makes brain-scanning helmets for children, emerged from research at the University of Nottingham, where researchers provide an “ongoing IP pipeline” into the startup, according to Chief Executive Officer David Woolger. While the academic and public health care infrastructure is a clear boon to the startups, it has its limits.

British universities have been criticized for taking too much equity in fledgling companies, potentially stifling growth opportunities. Woolger said Nottingham has a 25% stake in Cerca, for example, but is in discussions about decreasing its share.

And many health startups are reliant on selling to the National Health Service, an institution facing a deepening crisis with a checkered history of incorporating new tech. “It’s a remarkable asset because it’s a cradle-to-grave, one-payer system,” said Dingemans.

“But it’s very difficult to access.”

Even when a startup can hitch up with the NHS, it isn’t always a ticket to success. Babylon Health, a British telehealth provider, declared bankruptcy earlier this year despite a wide NHS partnership.

Many companies that cut deals with the NHS must still pursue commercial deals in the US to grow, said Irina Haivas, a partner in London at venture firm Atomico, which backs Healx and other life science startups.

Biotech firms don’t see as much of this pressure, as they’re less reliant on selling directly to local healthcare providers. Still, these startups typically face much longer time frames for clinical trials and business deals, on top of difficult of lab work.

Yet investors bankrolling them are drawn to the potential outsized returns if these startups break into pharmaceuticals, medicine and health systems — all huge global markets. “In the short-term, they’re obviously harder to build,” Haivas said.

“But they have more uncapped upside if you do build them.”

–With assistance from Jessica Nix.

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.