By Tim Hepher and Padraic Halpin

WASHINGTON/DUBLIN (Reuters) – Boeing’s first strike in 16 years could further compound global shortages of jetliners that have been pushing up airfares and forcing airlines to keep older jets flying longer, industry executives and analysts said.

The U.S.

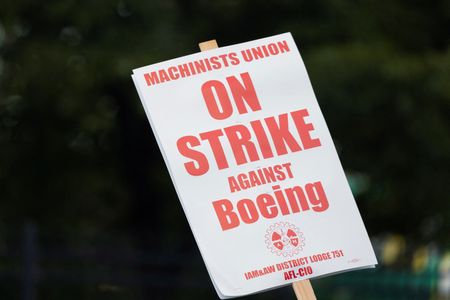

planemaker’s West Coast workers went on strike at midnight on Friday after overwhelmingly rejecting a contract deal, halting production of Boeing’s workhorse 737 MAX.

It is Boeing’s first strike since 2008, and Boeing Chief Financial Officer Brian West warned a prolonged walkout could hurt output and “jeopardize our recovery”.

“Boeing is a systemically important company for global aviation,” Ross O’Connor, chief financial officer of Irish leasing company Avolon, told Reuters on Friday.

A strike “could have an impact on production levels, which could exacerbate some of the supply shortages that are in the market at the moment for sure,” he said after Avolon announced it had acquired a large portfolio of jets from Castlelake.

Airlines have struggled to expand capacity to meet rising demand as supplies of jetliners are curtailed by parts shortages, industry-wide recruitment problems and overloaded maintenance shops.

Analysts have been warning the most promising part of the industry’s all-important business cycle could run out before airlines have a chance to enjoy the full benefits of demand.

“It’s going to be a significant amount of time before we see that balance.

I’m starting to evolve the hypothesis that it won’t be (extra) supply that corrects it, but instead a softening of demand,” said Rob Morris, global head of consultancy at Cirium Ascend.

Some say high air fares – although good for airlines in the short term – could themselves accelerate that tipping point.

“My view is that (average fares) will rise; and when ticket prices go up, then all other things being equal, you have lower traffic levels,” said aviation economist Adam Pilarski, senior vice-president at AVITAS consultancy.

As Boeing halts production of its most-sold jet, European rival Airbus is also struggling to meet its goals.

Airbus Chief Executive Guillaume Faury expressed optimism at a U.S. Chamber of Commerce conference this week that the European planemaker would meet a recently lowered target of 770 deliveries this year, following a profit warning and engine supply glitch in the summer.

But following a short-lived spike in deliveries in July, industry sources questioned how comfortably the world’s largest planemaker would exceed last year’s 735.

Dwindling numbers of planes in storage and record-high utilization of existing planes confirm the supply squeeze.

FLEET AGE RISING

For now, Boeing’s lower production levels compared to Airbus may limit the incremental effect of the strike.

Yet analysts said airlines have little room to maneuver.

With leasing companies also running out of available capacity, carriers need to keep existing jets flying longer.

For most of the past 15 years, the average age of the fleet declined as airlines and leasing companies took advantage of low interest rates to invest in new fuel-saving jets.

In 2010, the average age of the widely flown single-aisle jet fleet was about 10.2 years, according to Cirium data.

After dipping to 9.1 years during the pandemic as airlines grounded fleets, the age started growing again. It now stands at 11.3 years “and still heading upwards,” Morris said.

That is despite efforts to reach net zero emissions by 2050, which rely partly on modernizing the planes in service.

“It must mean that we’re burning more CO2 than we should be because we’re using more old aircraft…so one of the things that can go wrong is sustainability,” Morris said.

The airline industry says it is confident of reaching a target of net zero emissions by 2050.

(Additional reporting by Rajesh Kumar Singh, Allison Lampert; Editing by David Gregorio)