(Bloomberg) — Sign up for the New Economy Daily newsletter, follow us @economics and subscribe to our podcast.

Judging by the record number of people who’ve quit their jobs in the pandemic -– the so-called Great Resignation -– millions of Americans don’t really like their work.

Which doesn’t mean they’re not worried about losing out to robots — there’s an undercurrent of fear that automation is poised to displace human labor anyway. And the pandemic has triggered or heightened a whole range of other anxieties about working life, from job quality, security and mobility to the strength of social safety nets.

In a new book titled “The Work of the Future: Building Better Jobs in an Age of Intelligent Machines,” a team of Massachusetts Institute of Technology researchers published the results of a four-year project that examined these questions and plenty more.

Following is a summary of some of their findings and advice, illuminated by a conversation with two of the book’s authors.

Use Technology Better

The U.S. is short of workers right now, and may face a labor squeeze well after Covid, too. That suggests the key question isn’t whether there will be enough jobs — it’s whether those jobs will be good ones.

Part of the trick will be to find better ways to use technologies that already exist. Zoom calls have been around for a while, but it took the current crisis to push corporate managers into finding the most effective ways to use them.

In many industries, from meatpacking and warehousing to health care, the pandemic has accelerated the use of robots or computerization. But there’s been hiring in those industries, too, so workers aren’t necessarily getting replaced.

“Those things pull technologies from the future, five years closer to the present,” says David Autor, an MIT economics professor and one of the book’s co-authors.

The economy stands to benefit by becoming more productive, but that’s not true of every kind of automation. Self-checkout counters at supermarkets are an example of the “so-so” kind. “They waste your time,” Autor says. “They’re actually shifting work onto customers.”

The U.S. could tweak the tax system so it doesn’t encourage business spending on every kind of automation, regardless of whether it helps workers or the wider economy, the authors say.

Train More People

Taxes could be deployed to encourage training instead.

“There’s so many incentives and breaks that companies receive for investment in capital,” says Elisabeth Reynolds, who co-wrote the book as director of the MIT task force, and has served on the Biden administration’s National Economic Council since last year. “We really want them to lean in on the investment in human capital.”

The U.S. government spends less on “active labor market policies” — which include improving job readiness and help in finding suitable work — as a share of its economy than all its developed-country peers, according to OECD data from 2017. However, American business has put more money into training since then.

More of the training needs to be geared toward helping people without college degrees to get middle-class jobs, an area where the U.S. lags behind European countries like Germany, the book argues.

That’s something businesses are already looking at. Insurer Aon Plc, for example, dropped a degree requirement for some positions and organized its own specialized training via a local community college. International Business Machines Corp. and PwC have also relaxed their credential criteria.

Invest in Research

There’s plenty of innovation in the U.S. economy, and often it draws on past research funded by the government, whether it’s in aeronautics and computer science or medicine. But there’s less of that investment happening right now. Relative to historical levels –- and to peers or competitors, from Germany to China -– federal spending on research and development has fallen.

Those past investments “created enormous growth and opportunities,” Reynolds says. However, “the fruits of innovation, that productivity in the country, has not been shared across the board.”

The government should be plowing cash into the kind of “long-term, fundamental” research that businesses don’t have the incentive to take on, and that addresses important social problems like health care and climate change, the book — also co-authored by MIT aeronautics professor David A. Mindell — argues.

It should encourage technologies that augment human labor, rather than replace it, and try to spread innovation more evenly, both by geography and size of firm. In cases where public support turns into private profit -– the government lent money to Tesla Inc., now the world’s most valuable carmaker, in its early days -– an equity stake can help taxpayers enjoy some of the upside.

The Pentagon’s moonshot research arm, Darpa, is often cited as a successful incubator of innovations that turn out to be useful across the economy. The Biden administration wants to establish similar outfits for the health and construction industries.

Strengthen Safety Nets

Training can help people move upward. Automation will replace some rote tasks. Still, for the foreseeable future, some people will be doing jobs like cooking burgers –- and in the U.S. they get a worse deal than in most of the rich world.

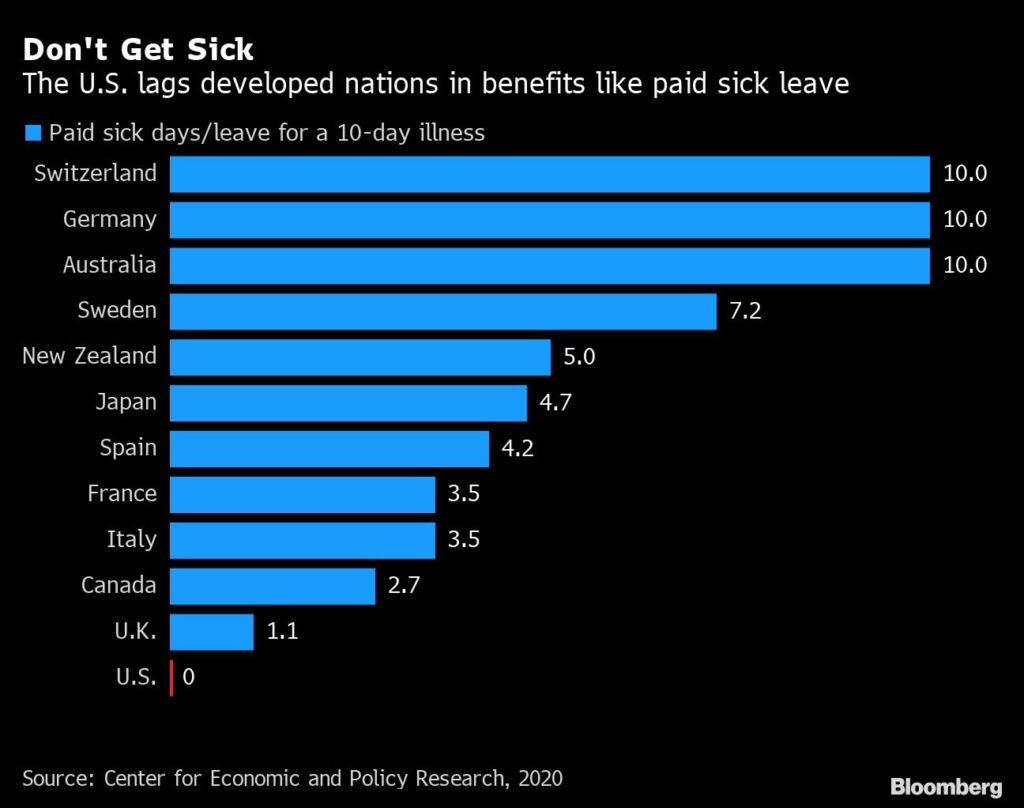

As well as raising minimum wages, the U.S. needs to overhaul its benefits system so more employees enjoy the protections that are standard elsewhere, like paid vacation and sick leave, the book argues. In the pandemic, emergency programs offered unemployment insurance and other safety-net provisions to part-time and freelance workers, but those measures have since expired.

“We have two different employment regimes that are just night and day,” says Autor. One is built around the New Deal of the 1930s, when jobs were full-time and often stable for life; the other, which encompasses the growing gig workforce, offers Social Security but “almost no other protections.”

“What we need is a system that is more scalable than that,” he says.

Help Workers Make Their Voice Heard

U.S. labor laws are rooted in an economy that no longer exists, the book argues. Union membership outside of the public sector has plunged, one reason why so many jobs are badly paid.

Entire industries -– including some of the fastest-growing, like home care –- lack institutions for collective bargaining.

That’s partly down to the traditional setup of American unions, which organize company-by-company instead of across sectors like in some other developed countries, according to Autor.

“We need to be able to open up the model of worker voice, to try out new experiments,” he says.

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.