Russian President Vladimir Putin’s two decades of relations with the West, initially marked by fascination over what the ex-KGB agent stood for and then bursts of cooperation, have now reached a point of no return with his invasion of neighbouring Ukraine.

The attack has created an indelible rupture between Russia and the European Union and United States as long as Putin stays in power, with Moscow now likely to turn to China as its main ally.

But this appeared in no way inevitable — Russia spent much of Putin’s rule as a member of the G8 club of top nations and he claimed that in 2000 he even suggested to US president Bill Clinton that Russia could join NATO.

When Putin was promoted by an ailing president Boris Yeltsin in 1999 from security chief to Russian prime minister and then his successor, the West had little idea who he was.

At a meeting with Putin in June 2001, US president George W. Bush famously declared that he had looked the new Russian leader in the eye and “was able to get a sense of his soul.”

Putin remained an enigma for most Western capitals.

But despite the crises prompted by the Russian invasion of Georgia in 2008 and the annexation of Ukraine’s Crimea in 2014, cooperation continued often intensively.

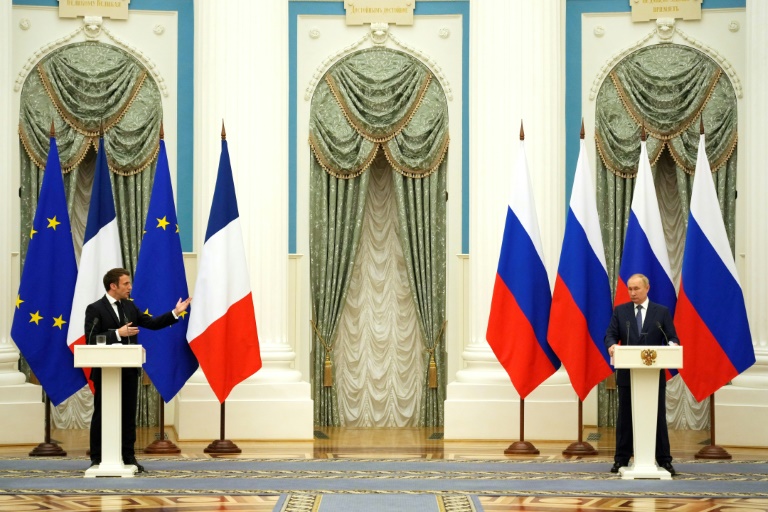

Few Western leaders have invested as much in a relationship with Putin than French president Emmanuel Macron.

He argued in a famous interview with the Economist magazine in November 2019 that NATO was brain dead and Europe needed a strategic dialogue with Russia.

Examining Russia’s long-term strategic options under Putin, Macron said in the interview that Russia could not prosper in isolation, would not want to be a “vassal” of China and would eventually have to opt for “a partnership project with Europe”.

Macron notably described Putin as a “child of Saint Petersburg”, the former Russian capital built by Peter the Great as a window onto the West.

Even last weekend, Macron was engaged in frenetic last minute diplomacy to prevent catastrophe, even trying to broker a summit between Putin and US President Joe Biden.

– ‘Chosen unilaterally’ –

But announcing the invasion of Ukraine on February 24, Putin went back to a litany of historic and recent political grievances to justify the move.

He notably repeated his arguments that Russia had been stabbed in the back by the West with the “cynical deception and lies” over NATO expansion.

In a landmark 2007 speech to the Munich security conference, Putin had lashed out at the role of the United States, saying a world of “one master, one sovereign” was “pernicious” for all.

But for Macron only one person is now to blame for the situation. “War has returned to Europe, this was chosen unilaterally by President Putin,” he said Saturday.

Former German chancellor Angela Merkel, who had more experience with Putin than any other Western leader during 16 years in power and could also converse with him directly in Russian, said: “Russia’s war of aggression marks a profound turning point in European history after the end of the Cold War.”

Russia now finds itself targeted by the toughest sanctions ever agreed against Moscow by the EU, US and UK and facing the collapse of key projects such as the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline to Germany.

– ‘Junior partner’ –

Its airlines are being refused the right to fly over the territory of some European countries, its teams are no longer welcome for matches and even artists who fail to condemn the invasion risk being ostracised in the West.

“We have reached the line after which the point of no return begins,” Russian foreign ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova said on Russian television.

For now, Putin may find some solace in his relationship with China, although Beijing conspicuously abstained over a UN resolution condemning the Russian aggression rather than echoing Moscow’s veto.

“Cut off from West, Russia has no choice but to become junior partner of China,” argued Charles Grant, director of the London-based Centre for European Reform.

“Beijing is ambivalent on invasion — it won’t criticise Russia in public and blames the US — but values stability and territorial integrity.”

Dmitry Trenin, director of the Carnegie Moscow Centre, forecast “wide-ranging” repercussions of the invasion which marked the “end of post-Soviet era for Russia” and heralded a period of “much more reliance on China”.