(Bloomberg) — No question about it, parts of the blank-check world are rife with sketchy accounting and gut-wrenching stock drops. Nevertheless, lenders to a business run by private equity might find they’re better off if it’s merged with a SPAC.

That’s what some credit investors and analysts are concluding after poring over potential deals that would combine PE-owned companies with a special-purpose acquisition company.

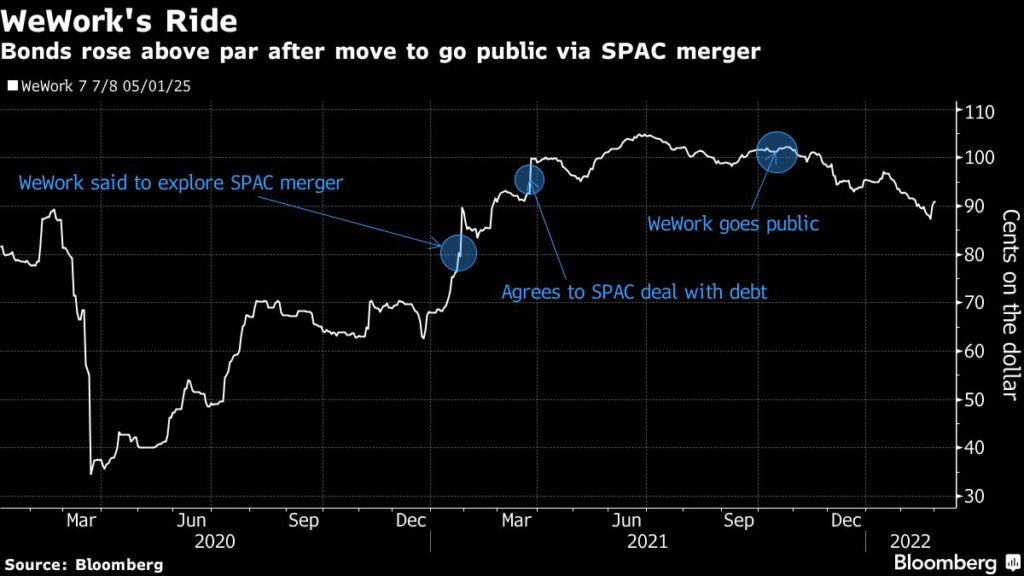

Bondholders of WeWork Inc.

earned a paper profit of 20% last year, showing the kinds of gains that are possible. More might be in the wings, with BC Partners-backed PetSmart Inc. and Warburg Pincus’s Allied Universal reportedly eyeing SPAC tie-ups.

The attraction is twofold: a private company gets cash from selling itself to a SPAC, thus improving its creditworthiness, and the sale diminishes control of PE owners, a sector with a reputation for maneuvers that weaken protection for creditors.

“It’s probably better for bondholders,” said Ross Hallock, head of high-yield research at Covenant Review.

The bigger equity cushion created by the cash helps, and “public companies typically don’t take actions that are detrimental to creditors to the same extent as private equity sponsored-backed companies do.”

In these cases, the risk of private equity ownership is theoretical — no one is suggesting the PE firms in those deals have done anything to hurt creditors.

Representatives for the firms, the SPACs and their targets declined to comment.

Some of the SPACs themselves are backed by PE firms, like the blank-check company controlled by KKR reportedly seeking to buy PetSmart.

The deal for Warburg’s Allied Universal could involve two SPACs also controlled by Warburg, as well as a SPAC backed by property billionaire Barry Sternlicht. KKR and Sternlicht’s vehicle declined to comment.

Hard Data

SPACs are called blank checks because they raise cash from investors through an initial public offering with the goal of buying a private business that’s not yet identified.

At first glance, they might seem an unlikely source of comfort to credit investors, who prefer hard data about cash flow over gauzy promises of future profits.

Some SPACs have suffered recently in part because of concerns about the quality of the companies they’ve targeted.

An index of SPACs that completed mergers is down more than 60% over the past year.

But back when the WeWork deal surfaced in January 2021, unsecured bonds for the office-sharing company soared from less than 80 cents on the dollar to full face value in less than three months.

(They’ve pulled back since then amid recent market turmoil.) Some of Allied’s secured notes and unsecured junk bonds rose after news of its potential deal broke earlier in February; PetSmart’s bonds also posted modest gains following the January disclosure.

Track Records

What’s more, some of targets have track records or hard assets.

PetSmart is the biggest pet retailer with about 1,650 stores in North America. Allied says its security business generates global revenue of $18 billion from about 85 countries. WeWork’s troubled history includes its disastrous over-expansion, but the overhauled business has about 912,000 workstations across 38 countries.

“The SPAC’s cash can be used for a combination of growth capital and to de-lever the target’s balance sheet, which is generally beneficial in cases when the target is being sold by a private-equity firm, which typically manage their companies with high leverage,” said Michael Broudo, an event-driven equities analyst at Oppenheimer & Co.

Data-center firm Cyxtera Technologies Inc., which went public via a SPAC, did just that when it used a chunk of the $493 million raised through its merger to pay down existing debt.

Cyxtera carried about $900 million in long-term debt as of Sept. 30, down from about $1.31 billion at the end of 2020.

It helps that publicly traded companies are often held to a higher standard than those that operate in the shadows of the private arena, analysts and investors said.

“You’ve got public market investors that place a value on a daily basis,” said John McClain, a high-yield portfolio manager at Brandywine Global Investment Management.

“There is intraday mark-to-market as opposed to private equity mark-to-make-believe.”

Cashing Out

Sometimes bondholders can redeem notes at a premium to current prices if a change of control clause is breached.

While the structure of some SPAC mergers make that unlikely for cases like Allied, Hallock sees benefits from the public market regardless because of the added cash cushion.

How much cash a merger brings is less certain than it was at the height of the SPAC bubble.

That’s because SPACs permit holders to redeem their shares if they don’t like the target that management picks.

Some short-term investors are using this to make a quick buck by buying the shares at a discount to the redemption price and turning them in after a deal is announced.

This leaves less capital for the merged company, and with enthusiasm for SPACs waning, redemption rates in February were hovering near 90%, according to analytics firm Boardroom Alpha.

For blank-check investors looking at PE-backed firms, it’s buyer beware, according to Brandywine’s McClain.

“If you’re an investor staring across the table from private equity trying to go public via SPAC, you certainly should have a lot of questions and want to dig into the disclosures,” he said.

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.