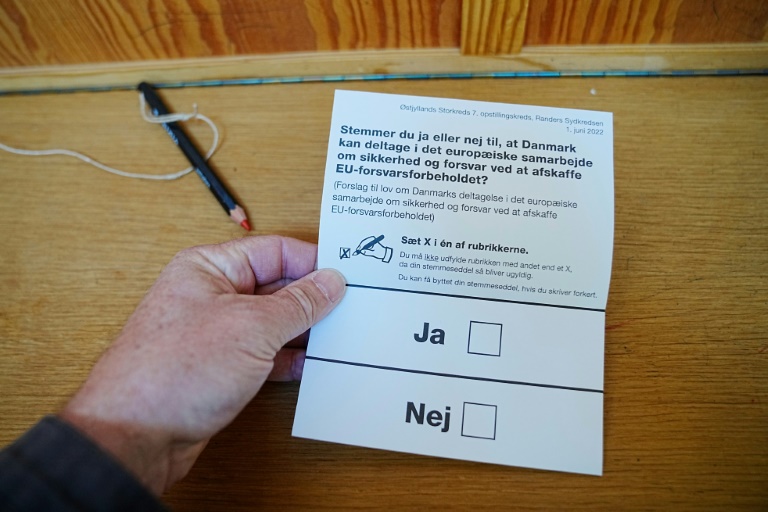

With the war in Ukraine forcing countries in Europe to rethink their security policy, Denmark voted Wednesday in a referendum on whether to join the EU’s common defence policy 30 years after opting out.

The vote in the traditionally Eurosceptic Scandinavian country of 5.5 million people comes on the heels of neighbouring Finland’s and Sweden’s historic applications for NATO membership.

“I’m voting yes with all my heart,” Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen said as she cast her ballot in her hometown of Vaerlose, on the outskirts of Copenhagen.

“Even if Denmark is a fantastic country — in my eyes the best country in the world — we are still a small country, and too small to stand alone in a very, very insecure world”, she said.

The defence opt-out means that the Scandinavian country, a founding member of NATO, does not participate in EU foreign policy where defence is concerned and does not contribute troops to EU military missions.

More than 65 percent of Denmark’s 4.3 million eligible voters are expected to vote in favour of dropping the exemption, suggested an opinion poll published on Sunday.

Analysts’ predictions have been cautious, however, given low-voter turnout expected in a country that has often said “no” to greater EU integration, most recently in 2015.

Polls opened across the country at 8:00 am (0600 GMT) and were set to close at 8:00 pm.

Final results were due around 11:00 pm (2100 GMT).

– ‘History changes’ –

At Copenhagen’s city hall, voting was busy in the early morning as Danes hurried to cast their ballots on their way to work.

“I think that these kinds of votes are even more important than earlier.

In times of war it’s obviously important to state if you feel that you want to join this type of community or not,” Molly Stensgaard, a 55-year-old scriptwriter, told AFP.

Mads Adam, a 24-year-old political science student, agreed.

“History changes and it affects us here in Denmark, and obviously we have to react to that.”

By midday, more than 25 percent of voters had cast their ballots, according to a survey of polling stations conducted by Danish news agency Ritzau.

Denmark has been an EU member since 1973, but it put the brakes on transferring more power to Brussels in 1992 when 50.7 percent of Danes rejected the Maastricht Treaty, the EU’s founding treaty.

It needed to be ratified by all member states to enter into force.

In order to persuade Danes to approve the treaty, Copenhagen negotiated a series of exemptions and Danes finally approved it the following year.

Since then, Denmark has remained outside the European single currency, the euro — which it rejected in a 2000 referendum — as well as the bloc’s common policies on justice and home affairs, and defence.

Copenhagen has exercised its opt-out 235 times in 29 years, according to a tally by the Europa think tank.

Frederiksen announced the referendum just two weeks after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and after having reached an agreement with a majority of parties in Denmark’s parliament, the Folketing.

– ‘Ukraine the major reason’-

At the same time, she also announced plans to increase defence spending to two percent of gross domestic product, in line with NATO membership requirements, by 2033.

“It was a big surprise”, said the director of the Europa think tank, Lykke Friis.

“Nobody thought that the government would put the defence opt-out to a national referendum”, she said.

“There’s no doubt that Ukraine was the major reason for calling the referendum.”

Eleven of Denmark’s 14 parties have urged voters to say “yes” to dropping the opt-out, representing more than three-quarters of seats in parliament.

Two far-right eurosceptic parties and a far-left party have meanwhile called for Danes to say “no”.

They have argued that a joint European defence would come at the expense of NATO, which has been the cornerstone of Denmark’s defence since its creation in 1949.

Denmark has held eight previous referenda on EU issues, most recently in December 2015 when it voted “no” to strengthening its cooperation on police and security matters for fear of losing their sovereignty over immigration.