Farmers in Uruguay, which is emerging as a supplier of soybeans to giant export plants in neighboring Argentina, are withstanding climate change through investments in technology to fight droughts.

(Bloomberg) — Farmers in Uruguay, which is emerging as a supplier of soybeans to giant export plants in neighboring Argentina, are withstanding climate change through investments in technology to fight droughts.

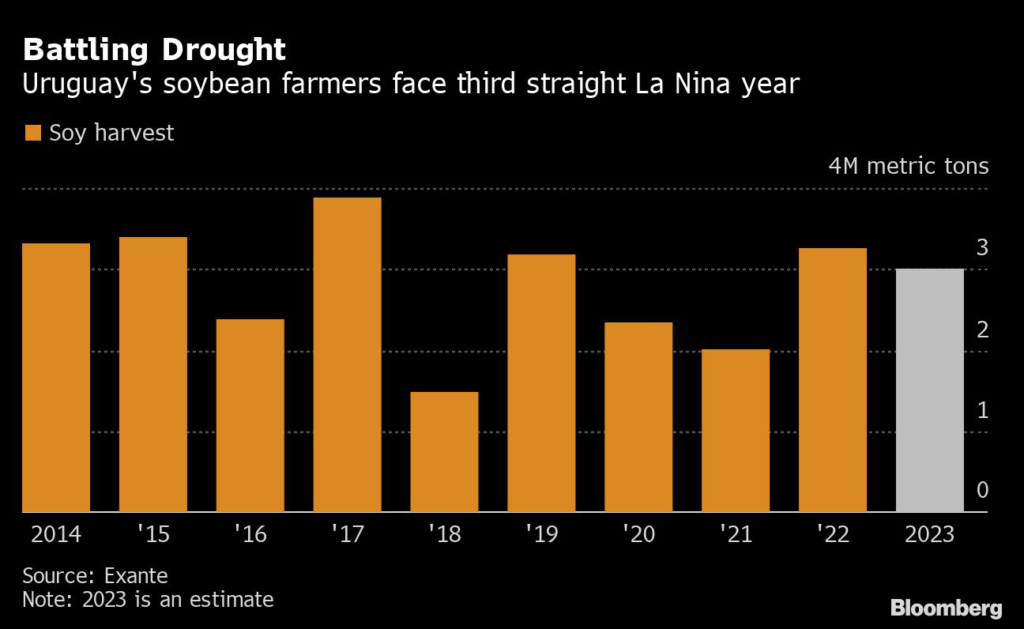

The harvest next year could reach about 3 million metric tons despite forecasts of dry weather in the River Plate region until January. That’d be only slightly lower than the 2022 crop, which benefited from timely rains, according to Montevideo-based consultancy firm Exante.

With climate change roiling farming and withering crops across South America, Uruguayan growers have embraced technology to beat the weather. In particular, they’ve invested heavily in hardier soy strains that bolster yields and in more precise applications of seeds and fertilizer, Marcos Guigou, executive director at Agronegocios del Plata, one of Uruguay’s biggest agriculture companies, said in an interview.

“Three or four years ago we used 80 kilograms of seed per hectare and today maybe we are using 60 kilograms,” Guigou said. By the end of the decade, according to Guigou, Uruguay could boost its soy yields to 25% higher than today’s levels.

Droughts that have crimped soy harvests in Argentina and Paraguay are paving the way for Uruguay to ship beans this year to Argentine processors, the world’s No. 1 exporters of soy meal and oil.

Uruguayan growers’ defiance in the face of extreme dryness provides a microcosm of how the global agriculture business is seeking out ways to adapt to climate change, including gene-modified soybeans that tolerate drought.

Family-owned Agronegocios del Plata manages about 44,000 hectares (109,000 acres) of farmland and 47,000 cattle. This season, the company plans to sow soy on about half that acreage. Plants could yield well, though they’ll depend on rains falling during key growth stages in February and March, Guigou said. A third straight La Nina-fueled drought is set to sputter out over the southern hemisphere summer.

“We think it could be an OK year,” he said.

Farmers are also planting increasing volumes of canola in recent years thanks to strong global demand for an oilseed used to make edible oils and biofuels. Almost 270,000 hectares were planted with canola this year, up from about 160,000 hectares in 2021, according to data compiled by the agriculture ministry.

“It’s likely that canola could reach 400,000 hectares in a couple of years,” Guigou said.

(Updates with farm technology in fourth paragraph and canola production in ninth and tenth paragraphs)

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.