(Bloomberg) — South Korean companies should make gender equality a key part of corporate governance to help combat the world’s lowest fertility rate, the country’s labor minister said.

(Bloomberg) — South Korean companies should make gender equality a key part of corporate governance to help combat the world’s lowest fertility rate, the country’s labor minister said.

“A key solution to the fertility, aging and productive problem is helping women raise children happily without having to worry about giving up jobs,” Korean Labor Minister Lee Jung-sik said. “But there still isn’t a noticeable level of effort for women at the environmental, social and governance level.”

The comments by Lee linking the fertility crisis with a lack of gender equality and insufficient corporate action are among the strongest yet by a cabinet member of Yoon Suk Yeol’s administration.

Lee also expressed concern about the potential labor-market impact of the recent crowd crush in Seoul and a continuing lack of safety awareness at workplaces.

Korea last year saw the number of babies expected per woman drop to 0.81, a result that shattered its own world record. The country is already on track to have the smallest share of working-age people in the developed world by the end of the century, according to UN data.

With fewer babies born and workers to support the economy, growth will slow and welfare spending will skyrocket, forcing policy makers to keep interest rates low and already-serious debt burdens heavy, economists say.

“What kind of country has a fertility rate of 0.8?” Lee said. “The shrinking workforce means fewer people, slower growth and more fighting for scarce resources and that’s not a sustainable society.”

Yoon’s government hasn’t announced any specific timeline for companies to bolster their ESG focus on women.

For now the government is largely continuing with previous administrations’ efforts to improve gender equality. Those include an affirmative action plan adopted in 2006 and a name-and-shame policy intended to grant fewer government deals to firms that fall well below the average of their peers in hiring female workers and boosting benefits for mothers.

As part of further ESG efforts, commercial banks could reinvest some of their earnings in building more nurseries in traditional office space given that more work is done online, Lee said.

“Korean women are among the world’s most educated, yet still account for a ridiculously small share of the workforce,” Lee said.

The rise in female participation in Korea’s workforce and management positions has failed to maintain its earlier pace in recent years. That has coincided with the further drop in fertility and underscores the challenge for the government to achieve progress without help from businesses.

Some corporate culture works as a barrier for companies looking to follow and encourage more women to take time off for children, Lee said, citing “nunchi” from bosses and colleagues, a term that alludes to unspoken pressure to follow customary practice.

Korea has the smallest share of parents going on leave for children in the developed world, a major factor behind it having the world’s lowest fertility rate.

On top of a glass ceiling, a lack of a work-life balance and pressure against taking maternity leave at work, women face an almost exploitative share of childcare and housework, Lee added.

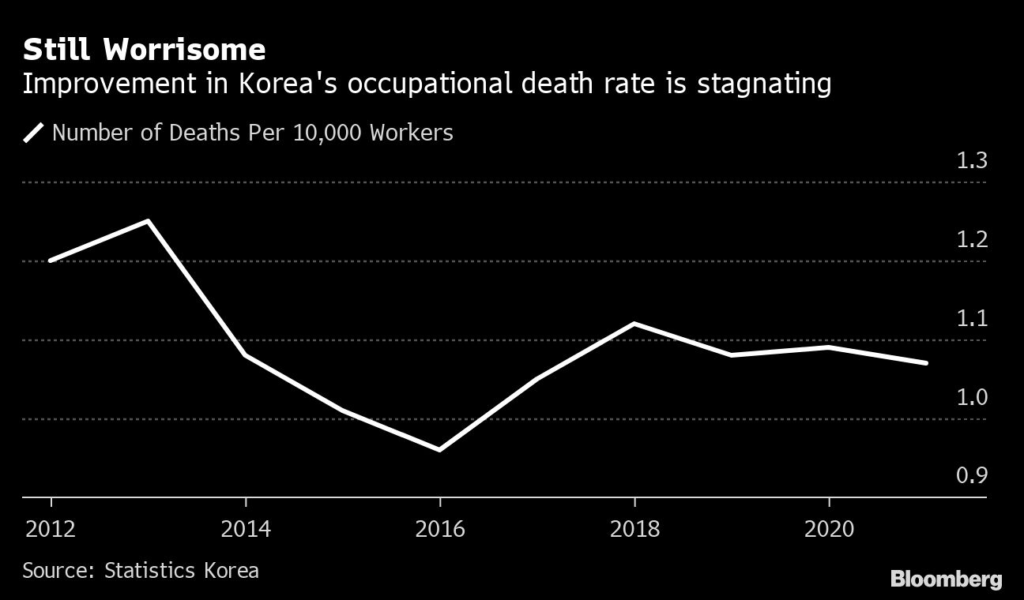

Among other issues weighing on Lee’s mind is the fact Korea still has a relatively high number of fatal injuries among Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development members.

In a high-profile case, a young woman died after being pulled into a machine at a bakery factory, prompting Yoon to call for a probe. At least two dozen more workers have since died in separate accidents, according to the Korea Occupational Safety and Health Agency.

Lee said his ambition is to push the rate of occupational deaths to the OECD average by the end of Yoon’s five-year term.

Korea is undergoing a period of soul-searching as it investigates the cause of the crowd crush that killed more than 150 people in the worst disaster since the 2014 Sewol ferry sinking.

Lee expressed his remorse for those who died and said the tragedy also adds to economic uncertainties and raises concerns for jobs.

“This can’t be good for the economy,” he said. “We’re most fearful it may lead to a potential vicious cycle of job insecurity that also stems from economic slowdowns and industrial changes.”

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.