By Tony Munroe and Yew Lun Tian

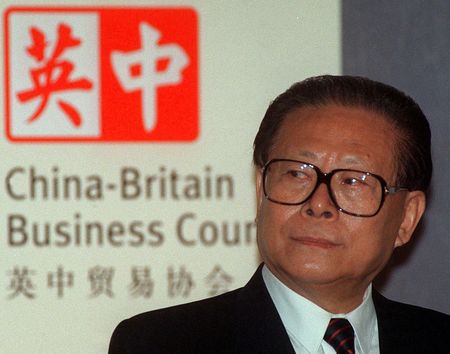

BEIJING (Reuters) – Former Chinese President Jiang Zemin, who led the country for a decade of rapid economic growth after the Tiananmen crackdown in 1989, died on Wednesday at the age of 96, prompting a wave of nostalgia for the more liberal times he oversaw.

Jiang died in his home city of Shanghai just after noon on Wednesday of leukaemia and multiple organ failure, Xinhua news agency said, publishing a letter to the Chinese people by the ruling Communist Party, parliament, Cabinet and the military.

“Comrade Jiang Zemin’s death is an incalculable loss to our Party and our military and our people of all ethnic groups,” the letter read, saying its announcement was with “profound grief”.

Jiang’s death comes at a tumultuous time in China, where authorities are grappling with rare widespread street protests among residents fed up with heavy-handed COVID-19 curbs nearly three years into the pandemic.

The zero-COVID policy is a hallmark of President Xi Jinping, who recently secured a third leadership term that cements his place as China’s most powerful leader since Mao Zedong and has taken China in an increasingly authoritarian direction since replacing Jiang’s immediate successor, Hu Jintao.

China is also in the midst of a sharp economic slowdown exacerbated by zero-COVID.

Even though Jiang put down student protests in Shanghai that were part of the wave of pro-democracy demonstrations that culminated in the bloody crackdown at Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, some Chinese expressed nostalgia for Jiang’s era as a time of optimism as well as hope for economic liberalisation and political freedom.

Jiang, though he could have a fierce temper, also had an informal and even quirky side, sometimes bursting into song, reciting poems or playing musical instruments – in contrast to his buttoned-up successor Hu, as well as to Xi.

Many posted videos and pictures online of Jiang’s meetings with former U.S.

President Bill Clinton, including one scene where the pair are all smiles as Jiang conducts a military band for part of the Chinese national anthem.

Numerous users of China’s Twitter-like Weibo platform described the death of Jiang, who remained influential after finally retiring in 2004, as the end of an era.

“I’m very sad, not only for his departure, but also because I really feel that an era is over,” a Henan province-based user wrote.

“As if what has happened wasn’t enough, 2022 tells people in a more brutal way that an era is over,” a Beijing Weibo user posted.

Alfred Wu, associate professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy in Singapore, tweeted: “Jiang Zemin is a legend.”

“Now we are ‘too simple, sometimes naive’ as we thought the regime would march towards openness, transparency, and democracy,” he said, referencing a furious dressing-down Jiang gave to Hong Kong reporters in 2000.

PLUCKED FROM OBSCURITY

The online pages of state media sites including the People’s Daily and Xinhua turned to black and white in mourning.

Xi, meeting Lao President Thongloun Sisoulith shortly after Jiang had died, said China would turn “our grief into strength”, according to state media.

Wednesday’s letter described “our beloved Comrade Jiang Zemin” as an outstanding leader of high prestige, a great Marxist, statesman, military strategist and diplomat and a long-tested communist fighter.

Jiang was plucked from obscurity to head China’s ruling Communist Party after the Tiananmen crackdown, but broke the country out of its subsequent diplomatic isolation, mending fences with the United States and overseeing an unprecedented economic boom.

He served as president from 1993 to 2003 but held China’s top job, as head of the ruling Communist Party, from 1989 and handed over that role to Hu in 2002.

He only gave up the position as head of the military in 2004, which he also assumed in 1989.

When Jiang retired, it was said by sources close to the leadership at the time that everywhere Hu looked he would see the supporters of his predecessor.

Jiang had stacked China’s most powerful leadership body, the Politburo Standing Committee, with his own protégées, many of them from the so-called “Shanghai Gang”.

But in the years after Jiang retired from his final post, the military commission chairmanship in 2004, Hu consolidated his grip, neutralised the Shanghai Gang and successfully anointed Xi as successor.

(Reporting by Tony Munroe, Yew Lun Tian, Ben Blanchard, Eduardo Baptista and Martin Quin Pollard; Editing by Andrew Heavens and Nick Macfie)