A jump in Baltic shipments helped crude volumes rise to 3.8 million barrels a day last week

(Bloomberg) — Russia’s seaborne crude exports soared last week to the highest level since April, suggesting that the country has — for now — overcome an initial hit to flows that followed European sanctions.

Aggregate volumes of Russian crude rose by 876,000 barrels a day, or 30%, to 3.8 million in the week to Jan. 13. Baltic shipments were up by 626,000 barrels a day from the previous week, while those from the Black Sea and the country’s Pacific ports also expanded.

The increase also lifted the country’s four-week average, which smooths out peaks and troughs in what are noisy weekly data. The jump in the four-week average was boosted as a mid-December, weather-related slump that saw weekly flows collapse by more than half fell out of the calculation. And the surge in exports by sea has been partly offset by a drop in pipeline flows to Europe, with deliveries to Germany halted since the start of the year.Inflows to the Kremlin’s war-chest from crude export duties rose much less sharply. All of the shipments in the latest week attracted duty at the low January rate, while several cargoes that were shipped the previous week were taxed at the December rate, which was more than two-and-a-half times as high. That was due in part to a change in the formula used to calculate duty rates, as the country continues its long shift away from taxing exports by increasing the burden on production.The data are highly volatile, depending on the timings of when individual shipments depart and things like weather conditions and work at ports.

The European Union’s import ban on Russia crude has led to much longer voyages for shipments, with journeys now taking an average of 31 days from Baltic ports to India, compared with just seven days from the same terminals to Rotterdam and about half that to Poland. That’s putting more pressure on the dwindling fleet of ships whose owners are willing to haul Russian cargoes.

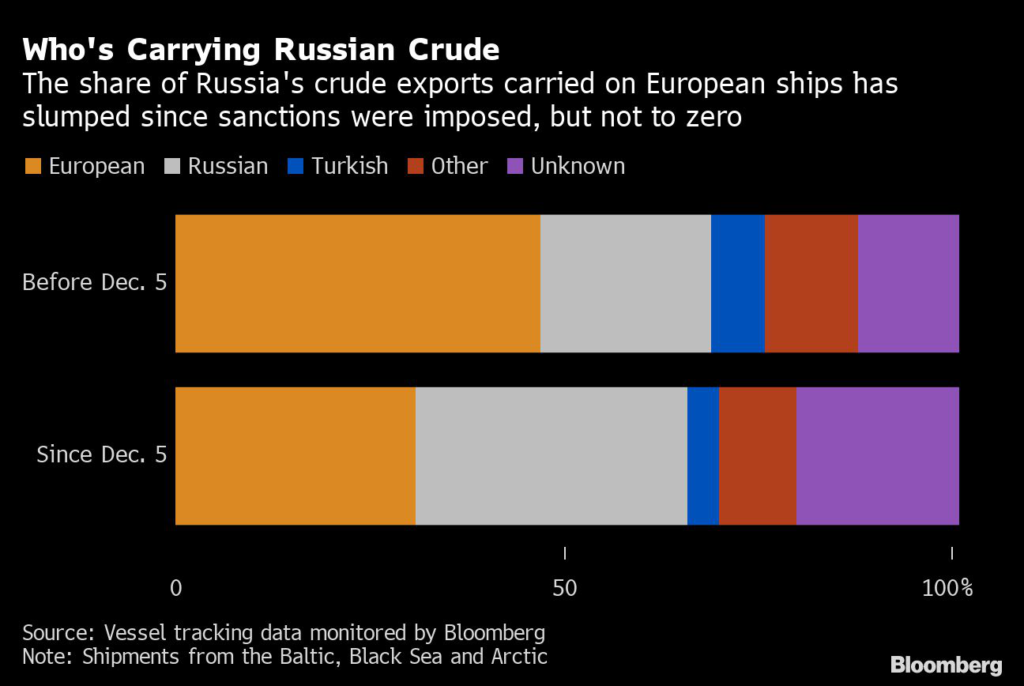

The country is increasingly reliant on its own ships and a so-called “shadow fleet” of usually older ships owned by small, often unknown companies that have sprung up in recent months. European-owned tankers can still carry Russian crude, as long as it is sold at a price below a $60 a barrel cap, introduced at the same time as the import ban. But fewer are now doing so.

There has also been a resurgence in ship-to-ship transfers of cargoes in the Mediterranean, with cargoes either being combined onto larger vessels or shifted from ice-class tankers onto others in order to free up those ships needed for operations in the Baltic in the winter months.

Transfers have been visible both off the Spanish north African city of Ceuta and off the Greek coast near Kalamata. The VLCC Lauren II has completed the transfer of three 100,000-ton cargoes at Ceuta and the Sao Paulo took two before heading through the Suez Canal. Lauren II is now heading around Africa to Asia. The VLCC Monica S completed a similar maneuver with an aframax off Ceuta on Jan. 14-15, becoming the third supertanker to do an STS of Urals at the site over the past month.

Elsewhere, shuttle tankers that haul Russia’s Sokol crude are waiting much longer than usual to transfer cargoes to other ships off the South Korean port of Yeosu, reducing the number of cargoes they are able to lift each month.

Tankers hauling Russian crude are becoming more cagey about their final destinations. Vessels carrying more than 29 million barrels of Russian crude, the equivalent of 1.05 million barrels a day of exports, left port showing no clear final destination in the four weeks to Jan. 13.

Crude Flows by Destination:

On a four-week average basis, overall seaborne exports rose by 550,000 barrels a day from a revised figure for the period to Jan. 6. At 3.058 million barrels a day, four-week average flows are the highest since November. Shipments to Asia soared, while those to Europe have dried up almost completely.

All figures exclude cargoes identified as Kazakhstan’s KEBCO grade. These are shipments made by KazTransoil JSC that transit Russia for export through Ust-Luga and Novorossiysk.

The Kazakh barrels are blended with crude of Russian origin to create a uniform export grade. Since the invasion of Ukraine by Russia, Kazakhstan has rebranded its cargoes to distinguish them from those shipped by Russian companies. Transit crude is specifically exempted from the EU sanctions.

The volume of crude on vessels heading to China, India and Turkey, the three countries that emerged as the only significant buyers of displaced Russian supplies, plus the quantities on ships that are yet to show a final destination, jumped in the four weeks to Jan. 13 to average 2.84 million barrels a day. That’s up by 504,000 barrels a day from the period to Jan. 6, and the highest since Bloomberg began monitoring the flows in detail at the start of 2022. Previously, the number had fallen four times in a row.

With most of the ships yet to show destinations likely to end up in India or China, the recent slump in flows to Turkey has been particularly dramatic. Imports from Russia, which rose to almost 400,000 barrels a day in September, slumped to just 47,000 barrels a day over the past four weeks, vessel-tracking data monitored by Bloomberg show. That’s as low as they were before Moscow’s troops invaded Ukraine last February.

-

Asia

Four-week average shipments to Russia’s Asian customers, plus those on vessels showing no final destination, which typically end up in either India or China, jumped to a new high of 2.82 million barrels a day in the four-week period to Jan. 13.

While the volume heading to India appears to have slumped, history shows that most of the cargoes on ships initially showing no final destination end up there.

The equivalent of more than 560,000 barrels a day was on vessels showing destinations as either Port Said or Suez, or which have already been or are expected to be transferred from one ship to another off the South Korean port of Yeosu. Those voyages typically end at ports in India and show up in the chart below as “Unknown Asia” until a final destination becomes apparent.

The “Unknown” volumes, running at 485,000 barrels a day in the four weeks to Jan. 13, are those on tankers showing a destination of Gibraltar, Malta or no destination at all. Most of those cargoes go on to Asia, but some could end up in Turkey. An increasing number are being transferred from one vessel to another in the Mediterranean for onward journeys through the Suez Canal or on larger vessels around Africa.

-

Europe

Russia’s seaborne crude exports to European countries edged higher to 167,000 barrels a day in the 28 days to Jan. 13, with Bulgaria the sole European destination. These figures do not include shipments to Turkey.

A market that consumed more than 1.5 million barrels a day of short-haul crude, coming from export terminals in the Baltic, Black Sea and Arctic has been lost almost completely, to be replaced by long-haul destinations in Asia that are much more costly and time-consuming to serve.

No Russian crude was shipped to northern European countries in the four weeks to Jan. 13.

Exports to Mediterranean countries were unchanged from the previous week on both a weekly and a four-week average basis.

Turkey was the only destination for Russian seaborne crude into the Mediterranean, but flows there have fallen back to levels seen before Russian troops invaded Ukraine. Turkey was one of the countries that boosted imports after the war began and it is surprising to see flows falling back, as the country is not a party to the EU’s import ban and had been seen as a key market for the country’s crude after European buyers shunned Russian crude.

Flows to Bulgaria, now Russia’s only Black Sea market for crude, regained the previous week’s loss, rising to 167,000 barrels a day. Bulgaria secured a partial exemption from the EU ban, which should support inflows now that the embargo has come into force.

Flows by Export Location

Aggregate flows of Russian crude rose by 876,000 barrels a day, or 30%, in the seven days to Jan. 13, jumping to their highest on a weekly basis since April. The biggest increases were seen in flows from the Baltic and Black Sea ports, with a smaller gain in Pacific exports. Shipments from the Arctic were unchanged from the previous week.

Figures exclude volumes from Ust-Luga and Novorossiysk identified as Kazakhstan’s KEBCO grade.

Export Revenue

Inflows to the Kremlin’s war chest from its crude-export duty rose by $3 million, or 4%, to $61 million in the seven days to Jan. 13, while the four-week average income moved in the opposite direction, falling by $1 million to $87 million. The small increase in export duty revenue from such a big jump in flows reflects the fact that several cargoes loading the previous week attracted the much higher rate of export duty charged in December.

The January duty rate is $2.28 a barrel, based on an average Urals price of $57.5 a barrel, according to figures from the Russian Ministry of Finance. The drop from $5.91 a barrel in December is due in part to a change in the formula used to calculate duty rates for 2023, with the country moving away from taxing exports and shifting the burden to production as part of its multi-year tax maneuver. The plan sees export duty phased out entirely by the start of 2024.

Inflows to the Kremlin’s war chest from export duty on crude will fall further next month, with February’s duty rate set at $1.75 a barrel. That’s down by 23% from January and the lowest per barrel rate since June 2020, during the depths of the Covid 19 pandemic. The drop is the result of a decline in Urals prices over the measurement period, which ran from mid-December to mid-January. Russia’s benchmark grade averaged $46.82 a barrel according to ministry figures, a discount of almost $35 a barrel to Brent over the same period.

Origin-to-Location Flows

The following charts show the number of ships leaving each export terminal and the destinations of crude cargoes from the four export regions.

A total of 35 tankers loaded 26.6 million barrels of Russian crude in the week to Jan. 13, vessel-tracking data and port agent reports show. That’s up by 6.1 million barrels, or 30%, from the previous week. Destinations are based on where vessels signal they are heading at the time of writing, and some will almost certainly change as voyages progress. All figures exclude cargoes identified as Kazakhstan’s KEBCO grade.

The total volume on ships loading Russian crude from Baltic terminals jumped to its highest since September, increasing by 60% over the previous week. One cargo is heading to Cuba, while about one-third of the ships leaving the ports of Primorsk and Ust-Luga are showing no clear destination.

Shipments from Novorossiysk in the Black Sea recovered the previous week’s loss in the period to Jan. 13, though flows remained below 500,000 barrels a day for a fifth week.

Arctic shipments remained at the previous week’s two-month high, with three suezmax tankers leaving from Murmansk during the week. With all cargoes now heading to Asia via the Suez Canal, these larger vessels have replaced the aframaxes that were previously used for deliveries from the floating storage units at the port.

Flows from the Pacific rose to equal their highest level since at least the beginning of 2022, with 12 tankers loaded at the region’s three terminals.

Shuttle tankers carrying Sokol crude are now often waiting much longer than they used to before transferring their cargoes to other vessels off the South Korean port of Yeosu, which may slow shipments of the grade. The voyage from the De Kastri terminal to Yeosu typically takes less than three days, allowing vessels to complete the round trip in a little over a week, allowing time for the cargo transfer. But for one tanker that has been anchored off Yeosu since Dec. 23, the full journey could take about four times as long.

Note: This story forms part of a regular weekly series tracking shipments of crude from Russian export terminals and the export duty revenues earned from them by the Russian government.

Note: All figures exclude cargoes owned by Kazakhstan’s KazTransOil JSC, which transit Russia and are shipped from Novorossiysk and Ust-Luga as KEBCO grade crude.

Note: Data on crude flows can also be found at {DSET CRUDEJ }. The numbers, which are generated by a bot, may differ from those in this story.

Note: Aggregate weekly seaborne flows from Russian ports in the Baltic, Black Sea, Arctic and Pacific can be found on the Bloomberg terminal by typing {ALLX CUR1 }.

–With assistance from Sherry Su.

(Updates ninth paragraph with details of ship-to-ship transfer.)

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.