Mass strikes have marked France’s political landscape for years, while post-Thatcher Britain is known for its more flexible labor market. This week, however, the two countries could look similar as widespread protests are mirrored on either side of the English Channel.

(Bloomberg) — Mass strikes have marked France’s political landscape for years, while post-Thatcher Britain is known for its more flexible labor market. This week, however, the two countries could look similar as widespread protests are mirrored on either side of the English Channel.

In the UK, industrial strife has been building since the summer amid the worst cost-of-living crisis in a generation. With disputes dragging on throughout the public sector, unions are increasingly coordinating their action. Train drivers, teachers, airport staff and other civil servants will all walk out on Wednesday as part of demands for higher pay.

Before then, on Tuesday, France will be hit by strikes affecting similar sectors. French rail workers, teachers, airport staff, energy workers and public servants will protest Emmanuel Macron’s plan to slash deficits in the pension system by raising the minimum retirement age to 64 from 62.

Numbers Game

The Interior Ministry said 1.1 million people took part in previous marches, on Jan. 19, including 80,000 in Paris. Unions estimated the turnout at more than 2 million, including 400,000 in Paris.

Bloomberg calculations using French civil service ministry data showed that about 1.4 million public-sector workers, including teachers, health workers and civil servants declared themselves on strike on Jan. 19, broadly the same as the previous general strike in France in December 2019. This figure doesn’t include private-sector workers, many of whom were on strike too.

Read More: Macron Faces Prolonged Battle Over Pensions as Unions Dig In

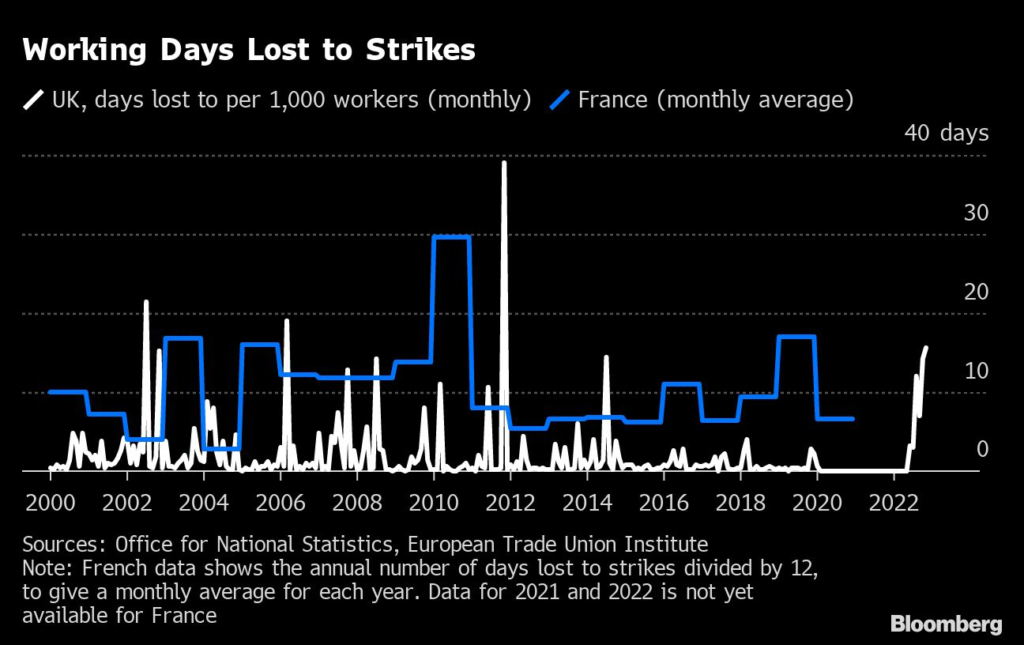

The UK’s Office for National Statistics said this month that 467,000 working days were lost to Britain’s strikes in November. In the six months since data-collection resumed following a break during the pandemic, the number of days lost reached its highest level since 1989-90, when Margaret Thatcher was prime minister.

Still, those protests could look minor compared with unions’ latest plans. Around 475,000 workers have a mandate to strike on Wednesday, according to Bloomberg’s calculations — close to the figure for all of November.

Labor groups are also planning widespread protests on the day, rallying against government plans to impose minimum service levels during strikes.

Continental Shift

Living standards are being squeezed across Europe. However, the UK has suffered a particularly sharp increase in industrial action compared with levels seen since the turn of the century.

Inflation in Britain remains in double digits, while many public sector workers were offered raises of less than 5% last year. That infuriated unions but ministers insist generous pay hikes risk embedding cost pressures and making everyone worse off.

Talks in many sectors remain in deadlock. On Monday, a teaching union said the government had “squandered an opportunity to avoid strike action” by resisting the demands for better real-terms pay.

With Prime Minister Rishi Sunak digging in and Macron similarly determined to push through his pension reforms, mass protests look set to become a common scene in Britain and France alike.

–With assistance from William Horobin.

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.