AIDS: Years of research but still no vaccine

Covid vaccines began to show promise just months after the novel coronavirus started spreading across the globe.

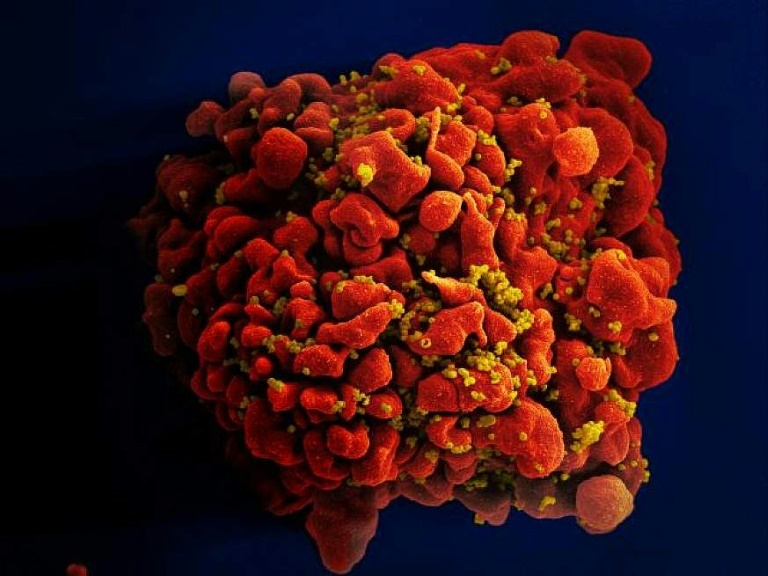

So why have decades of HIV/AIDS research yielded so little progress on a jab to prevent a disease that claimed some 680,000 lives in 2020?

As the globe marks World AIDS Day on Wednesday, why is there still no vaccine to protect people from the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)?

One answer is that the political will and colossal investment that have spurred on Covid vaccine development have largely been missing from AIDS vaccine research since HIV was discovered in 1983.

But another lies in the complexity of the science behind HIV.

“With COVID vaccines, researchers worry about the vaccine being able to fend off a handful of variants that have become particularly worrisome,” reads a June report by the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI).

“But for HIV, there are millions and millions of different viruses that have resulted from the virus’s stealth ability to rapidly mutate… It is this astonishing level of diversity that any HIV vaccine must contend with.”

Olivier Schwartz, head of the viruses and immunity unit at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, says that while most people can recover naturally from an initial coronavirus infection and thus acquire immunity, this is not the case for HIV.

“HIV mutates much more easily than Covid and so it is more difficult to generate so-called broadly neutralising antibodies that could prevent infection,” he said.

Only a handful of people naturally produce these antibodies when exposed to HIV.

Research into a vaccine has meant studying those rare responses, understanding how they work, and trying to replicate them in healthy people’s immune systems.

– An mRNA jab? –

Several dozen vaccines are being studied, with one by US firm Moderna seeking to use the same mRNA delivery method as its popular Covid vaccine.

The June report describing the research explains how the mRNA jab is meant to deliver instructions for a process called “germline targeting”.

This means “guiding the immune system, step by step, to induce antibodies that can counteract HIV”, the report explains.

So far, the technique is complex, involving an initial shot to activate important B-cells before several jabs attempt to spur the body into producing a range of antibodies.

Being able to visualise a way forward has given researchers hope, and some say it’s thanks in no small part to the pandemic.

“These last few years have seen unprecedented growth in our understanding of the immune system,” Serawit Bruck-Landais of French AIDS organisation Sidaction told AFP.

But even with seeming breakthroughs, Bruck-Landais says, progress on an HIV jab is “not enough to be able to say we will have an AIDS vaccine soon”.

The US clinical trials for the Moderna vaccine that were set to begin in August are still listed on the National Institutes of Health website as “not recruiting”.

– ‘Lack of investment’ –

Researchers looking into vaccines say they are overlooked in terms of funding.

“The market is too weak for pharmaceutical groups and there’s a disappointing lack of investment,” says Nicolas Manel, a research director at the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research (INSERM).

“Many researchers are very motivated, but they have to make do with the funds they have.”

In the absence of a vaccine, focus has historically been on promoting preventative measures like protected sex, clean needles, and overall better access to healthcare for marginalised populations.

Some 38 million people across the globe live with the virus.

Monsef Benkirane, research director at the France-based Institute of Human Genetics, points to important improvements in medicine that allow many people with HIV to live longer, healthier lives.

Importantly, by reducing an infected person’s viral load, HIV treatments today can vastly decrease or eliminate a person’s chances of transmitting HIV to another person.

But Benkirane says many people lack access to the treatments, while those who do have access sometimes struggle to follow through and take all the necessary medications.

“In addition to improving access to treatments, there are still problems with people actually sticking to the treatment regimens, even in Europe,” he said.